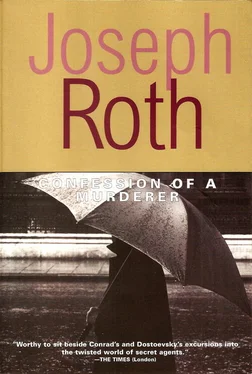

Joseph Roth - Confession of a Murderer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joseph Roth - Confession of a Murderer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, Издательство: The Overlook Press, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Confession of a Murderer

- Автор:

- Издательство:The Overlook Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Confession of a Murderer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Confession of a Murderer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Confession of a Murderer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Confession of a Murderer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Every moment I was afraid of meeting Lakatos. He might come into the hotel lounge. He might come into the great showrooms of the fashionable dressmaker where I sometimes went to fetch Lutetia. He might betray me every moment. He had me in his hand. He might even betray me to Lutetia — and that would be the worst. In proportion as my fear for Lakatos increased, grew also my passion for Lutetia. It was a sublimated passion, a passion, so to speak, of the second degree. For in reality, during those weeks, it was no longer a true love, it was a flight to passion, just as the doctors today call certain symptoms in women “a flight to sickness.” Yes, it was a flight to passion. I was only safe, sure of myself, sure of my own identity, during those hours when I held and loved Lutetia’s body. I loved it, not because it was her body, but because it was to a certain extent a refuge, a cell, a sanctuary, safe and secure from Lakatos.

Unfortunately there now happened what needs must have happened sooner or later. Lutetia, who believed as implicitly in my inexhaustible wealth as she would have liked to have believed in her rag-and-bone merchant story, needed money and more money. She needed more and more money. After a few weeks it became clear that she was just as mercenary as she was beautiful. Oh, not that she had tried secretly to put money by, in the way which characterizes so many middle-class women. No! She really spent it. She spent it!

She was like most women of her kind. She did not want to “use up” anything. But something in her wished to make use of opportunities, of all opportunities. Weak she was, and immeasurably vain. With women vanity is not only a passive weakness, it is also an extremely active passion, such as only games are with men. Again and again they keep giving birth to this passion; they incite it and at the same time are incited by it. Lutetia’s passion dragged me with it. Until then I had never dreamed how much a single woman could spend — and that always in the belief that it is only what is “absolutely necessary” Until then I had never dreamed how powerless a loving man is against the foolishness of a woman. And at that time I was striving to be a loving man; which amounted to the same thing as being really in love. It was just the foolish and unnecessary things that she did which appeared to me to be both necessary and natural. And I will admit that her foolishness flattered me and at the same time confirmed my sham princely existence — for I needed such confirmation. I needed all this outward confirmation: clothes for me and Lutetia, the servility of the tailors who measured me in the hotel with careful fingers as though I were a fragile idol; who scarcely had the courage to touch my shoulders and legs with the tape measure. Just because I was a Golubchik I needed all that which would have wearied a Krapotkin: the menial look in the porter’s eyes, the obsequious bowing of the waiters and servants, of whom I saw little more than their faultlessly shaved necks. And money — money I needed, too.

I began to earn as much as possible. I earned a lot — and I need not tell you how. Sometimes I remained a whole week hidden from Lutetia and the rest of the world. At such times I mingled with our political refugees. I visited the offices of unimportant little publications and miserable newspapers. I was even shameless enough to accept small loans from the victims I was tracking down; not because I needed the paltry sums of money, but in order to make it seem that I needed the money. In bare little rooms I shared the scanty meals of the hunted, the outcast, the hungry. I was debased enough now and again to attempt the seduction of refugee women who, often happily and sometimes from a sort of tragic sense of duty, gave themselves to a companion in distress. All in all, I was what I had always been, by birth and nature — a scoundrel. To a certain extent, I even proved to myself during those days that I was a scoundrel beyond redemption.

I was lucky. The Devil guided my every footstep. When I visited Solovejczyk on the appointed evenings, I could tell him more than most of my other colleagues. And I perceived from the growing contempt with which he treated me that I was rendering valuable services. “I underestimated your intelligence,” he said to me once. “After hearing of your foolishness in Petersburg, I thought you were a petty rascal. My respects to you, Golubchik! I shall pay you well.”—For the first time he had called me Golubchik, and he knew well enough that for me that name was like a thrust with a dagger. I took my money, a great deal of money, changed, drove back to my hotel, saw the backs and necks of the staff, saw Lutetia again, saw the nightclubs, the common and superior faces of the waiters, and forgot everything, everything. I was a prince. I even forgot the dreadful Lakatos.

I forgot him unjustly.

One mild spring morning I was sitting in the lounge of the hotel, and although the room had no windows it felt as though the sun were streaming in though every pore in the walls. I was bright and cheerful, without a thought in my head, entirely given up to the loathsome contentment with which life filled me. When suddenly Lakatos appeared. He was as gay as the spring itself. He was almost anticipating summer. He came in like a fragment of spring, detached from the rest of nature; wearing a far too light overcoat, a flowered cravat, and a gray top hat; swinging in his right hand the little cane which I knew so well. He addressed me alternately as “Highness” and “Prince,” and sometimes he even said, in the manner of small menials: “Your most gracious Highness!” Suddenly the whole of that bright morning darkened for me. How had I been faring all this long time, Lakatos asked me — so loudly, that everyone in the lounge heard it and even the porter in his office. I was monosyllabic. I scarcely answered — for fear, but also out of pride. “So your dear father recognized you?” he asked me softly, while he bent so close to me that I could smell his lilies-of-the-valley scent and the brilliantine which was wafted in heavy waves from his mustache. And I could see plainly a reddish shimmer in his bright brown eyes.

“Yes,” I said and leaned back.

“Then you will be pleased to hear,” he said, “what I have to tell you.”

He paused. I said nothing.

“Your dear brother arrived here yesterday,” he said calmly. “He is living in his house. He has a permanent residence in Paris. As every year, he intends to remain here for a few months. I believe you are now reconciled with him?”

“Not yet,” I said, and could scarcely conceal my impatience and tenor.

“Well,” said Lakatos, “I hope that will soon come to pass. In any case, I am always at your service.”

“Thank you,” I said. He got up, bowed low and went. I remained seated.

But not for long. I drove straight to Lutetia. She was not at home. I drove to the dressmaker’s shop. With a large bouquet I thrust my way in, as with a couched lance. I was able to speak with her for a few moments. She knew nothing of Krapotkin’s arrival. I left the shop. I sat down in a café and hoped that by concentrated thought I might arrive at some brilliant inspiration. But all my thoughts were contaminated with jealousy, hatred, passion, vengefulness. Soon I persuaded myself that it would be best to go to Solovejczyk and ask him to send me back to Russia. Then, once more, fear overcame me; fear of losing my present life, fear of losing Lutetia, my stolen name, everything that contributed to my existence. I thought for a moment of killing myself, but I had a horror of death. It was much easier, much better, but in no way pleasanter, to kill the Prince. To rid the world of him! Once for all to be free from that ridiculous youth, that really ridiculous and useless fool! But in the same moment, and with the ruthless logic dictated by my conscience, I said to myself that if he were a useless fool I was still worse, being both evil and harmful. But scarcely a minute later it seemed clear to me that the cause of my evilness and harmfulness was he alone, he, that superfluous creature, and that to kill him would be ethically justifiable. For, in destroying him, I should also destroy the cause of my corruption, and then I should be free to become a decent citizen, to atone, to repent, even to become a respectable Golubchik. But even while I was thinking of all this, I realized that I was far from possessing the necessary determination to commit a murder. At that time, my friends, I was not nearly clean enough to be able to kill. Whenever I considered destroying a certain person, it was synonymous to me, to my mentality, with the decision to ruin him in some way or other. We spies are no murderers. We only prepare the circumstances which must inevitably lead to a man’s death. I, too, thought no differently; I was incapable of thinking differently. I was a scoundrel by birth and nature, as I have already told you.…

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Confession of a Murderer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Confession of a Murderer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Confession of a Murderer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.