I can say no more now, but that, as above , being arriv’d in Holland , with my Spouse and his Son, formerly mention’d , I appear’d there with all the Splendor and Equipage suitable to our new Prospect, as I have already observ’d .

Here, after some few Years of flourishing, and outwardly happy Circumstances, I fell into a dreadful Course of Calamities, and Amy also; the very Reverse of our former Good Days; the Blast of Heaven seem’d to follow the Injury done the poor Girl, by us both; and I was brought so low again, that my Repentance seem’d to be only the Consequence of my Misery, as my Misery was of my Crime.

FINIS

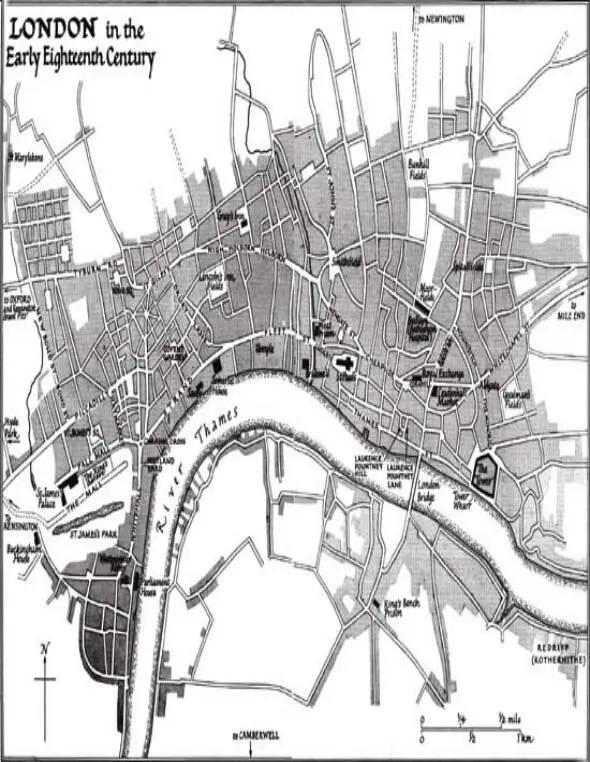

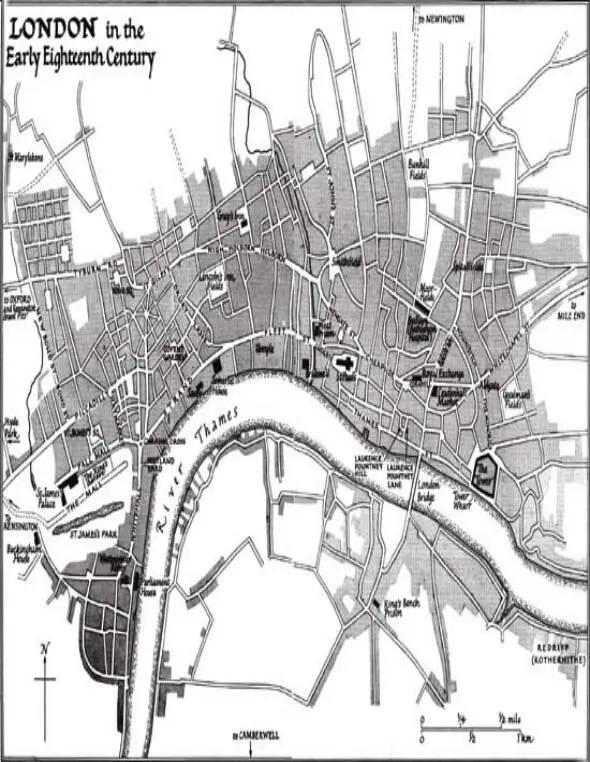

The notes have been made primarily to help the reader understand Defoe’s text, and only secondarily to direct his attention to considerations of related themes in Defoe’s other works. Historical, biblical, and other references are explained, unfamiliar place-names identified, and obsolete words glossed. When such words recur a second explanation has been given only when the recurrence is much later. I have relied heavily on such standard reference works as The Oxford English Dictionary, The Dictionary of National Biography, The Encyclopaedia Britannica (eleventh edition), and relevant volumes of The Oxford History of England . Early dictionaries, such as Edward Phillips’s (seventh edition, 1720) and Nathan Bailey’s (1730), were sometimes useful, and Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1775) was an occasional but indispensable supplement to the OED . For details about the buildings, place-names, and topography of London and neighbouring towns I found Edward Hatton, A New View of London, 2 vols. (1708), John Stow, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster , ed. John Strype, 2 vols. (1720), Defoe’s own A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–6), Henry B. Wheatley, London Past and Present , 3 vols. (1891), and Hugh Phillips, Mid-Georgian London (1964) especially useful. On social conditions in England in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the following works were most valuable: John Ashton, Social Life in the Reign of Queen Anne , 2 vols. (1882), Sir George Nicholls, A History of the English Poor Law , 3 vols. (1898), M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century (1925), Dorothy Marshall, The English Poor in the Eighteenth Century (1926), and Sidney and Beatrice Webb, English Local Government: The Old Poor Law (1927). For historical information about mental disease I consulted Gregory Zilboorg, A History of Medical Psychology (1941), Richard Hunter and Ida Macalpine, Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry, 1535–1860 (1963), and Michael V. De Porte, Nightmares and Hobbyhorses; Swift, Sterne, and Augustan Ideas of Madness (1974). The most useful works of reference on English dress were C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington, Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century 1955) and the companion volume for the eighteenth century (1957). Two works are in a class by themselves for they have no competitors; M. P. Tilley, A Dictionary of the Proverbs in England in the Sixteenth and Sevententh Centuries (1950) and John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America 1660–1775: A Handbook (1978). In many cases information was gleaned not from books but from correspondence with scholars who generously supplied me from their stores of specialized knowledge and who are thanked at the beginning of the book.

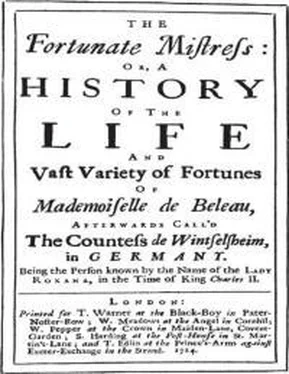

Titlepage. THE FORTUNATE MISTRESS : The original title of Defoe’s novel, now generally called Roxana , appears to have been adapted from Mrs Haywood’s Idalia; Or, The Unfortunate Mistress published in 1723, the year before Roxana .

* Here she tells my whole Story, to the Time that the Parish took off one of my Children, and which she perceiv’d very much affected him; and he shook his Head, and said some things very bitter, when he heard of the Cruelty of his own Relations, to me .

See Paul Alkon, Defoe and Fictional Time (University of Georgia Press, 1979), pp. 53–8, and my Defoe’s Art of Fiction (University of Toronto Press, 1979), pp. 126–7.

See The Weekly Journal (5 April 1719), reprinted in William Lee, Daniel Defoe: His Life and Recently Discovered Writings (1869), II, 32; and The Fears of the Pretender Turn’d into the Fears of Debauchery (1715), esp. pp. 31–4.

Early in January 1724, only six weeks before Roxana was published, the Bishop of London preached a sermon against masquerades, which brought forth a retort in verse from John James Heidegger, their chief organizer and, by royal appointment, Master of the Revels.

e.g., Mary Astell, Aphra Behn, Lady Chudleigh, and Hannah Wooley.

See Conjugal Lewdness (1727), especially pp. 101–3.

The Family Instructor, In Three Parts (1715); The Family Instructor, In Two Parts (1718); Religious Courtship (1722); The Great Law of Subordination Consider’d (1724); Conjugal Lewdness (1727); A New Family Instructor (1727).

See Two Discourses Concerning the Souls of Brutes (1683), pp. 201–2; and Michael V. DePorte, Nightmares and Hobbyhorses (The Huntington Library, 1974), p. 7.

not a Story, but a History : Although ‘History’ was used of any narration true or imaginary, here the writer is distinguishing between a narrative of fact and a ‘Story’, which Samuel Johnson in his Dictionary defines as ‘an idle or trifling tale’.

discover’d : revealed.

Excursions : digressions, additional comments.

Equipages : coaches and footmen.

Profit and Delight : The idea that the end of poetry – and by extension creative writing – is to inform and delight had become a critical commonplace. It received its classic formulation in Horace’s Ars poetica .

the Protestants were Banish’d from France : The Edict of Nantes (1598), granting religious liberty to French Protestants, was not revoked until 1685, but systematic persecution began about 1660 and was stepped up in 1681. The persecutions were particularly severe in the heavily Protestant province of Poitou, where the Marquis de Louvois, Louis XIV’s war minister, first introduced the dragonnades (billeting of unruly dragoons) in Protestant households. In 1681 Charles II, in response to public opinion, signed a Bill granting privileges to French Protestant refugees who sought asylum in England.

or something else : The attitude of Roxana and her father towards the refugees – that they were undeserving financial opportunists – is utterly out of line with Defoe’s own attitude. In The True-Born Englishman (1701) and elsewhere he vehemently defends immigration on the ground that the strength and prosperity of the country depends on the number of its inhabitants.

Spittle-Fields : originally open fields in the east of London belonging to the Priory and Hospital of St Mary Spital and by Defoe’s day a built-up area, well-known as a major centre of cloth manufacture. At the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes there was a considerable influx of French emigrants, who established silk weaving there.

Читать дальше