In vain were attempts made to learn the reason for the Marquise’s strange behaviour. She had the heaviest of fevers, didn’t want to know anything about the betrothal and asked to be left alone. To the question as to why she had suddenly changed her mind, and what made the Count seem more repellent to her than any other, she looked, distracted and with wide eyes, at her father and said nothing. The Colonel’s wife spoke up; had she forgotten she was herself a mother, to which she answered that in that case she must think more about herself than the child, and assured her once again, calling on all the angels and saints in heaven as witness, that she would not marry. Her father, who evidently saw her as being in an overexcited state of mind, declared that she must keep her word, then left her and gave orders for everything to do with the marriage after careful and written consultation with the Count. The Commandant then presented the latter with a marriage contract in which the Count would forgo all conjugal rights, binding him on the other hand to all the duties demanded of him. The Count sent the document back, drenched in tears, with his signature. When next morning the Commandant gave this document to the Marquise, her spirits had calmed down a little. Still sitting in bed, she read it through several times, gathered it thoughtfully together, opened and read it again and thereupon declared that she would be present at 11 o’clock at St Augustine’s Church. She got up, dressed without saying a word, climbed into her carriage with all her family as the clock struck, and drove off towards the church.

The Count was only allowed to join the family in the church porch. During the ceremony the Marquise stared rigidly at the altarpiece; she didn’t bestow one fleeting glance on the man with whom she exchanged rings. When the betrothal was over, the Count offered her his arm, but as soon as they were out of the church again the Countess bowed and took leave of him. The Commandant asked him if he would have the honour of seeing him sometimes in his daughter’s quarters. The Count muttered something nobody understood, raised his hat to the assembled company and disappeared. He moved into a house in M— in which he spent several months without even putting a foot in the Commandant’s house, where the Countess remained. It was only his gentle, dignified and absolutely exemplary behaviour whenever in any kind of contact with the family that he had to thank for being invited to the baptism after the Countess was delivered of a young son. She, with embroidered coverlets on her childbed, saw him only for a moment as he entered the door and greeted her from a respectful distance. Among the presents with which guests welcomed the newborn, he threw two sheets of paper into its cradle, one of which, it transpired after examination, was a gift of 20,000 roubles to the boy. The other was a will, which in the event of the Count’s death named the Countess as heir to his entire fortune. From that day on, at the instigation of the Colonel’s wife, he was frequently invited. The house was open to him and soon hardly an evening passed without him being there. As he had a feeling that he had been forgiven on all sides because of the world’s precarious nature, he resumed his wooing of the Countess—his wife—and after a year had elapsed received a second acceptance from her. A second marriage was also celebrated, happier than the first, after which the whole family moved out to V—. A whole row of little Russians now followed the first, and when the Count one day asked his wife in a happy moment why, on that dreaded 3rd, when she seemed ready to receive any villain of a man, she had fled from him as from a devil, she threw her arms round his neck and told him that he wouldn’t have seemed like a devil to her then if he hadn’t appeared like an angel to her when she first saw him.

For the text I used Die Marquise von O… in Heinrich von Kleist, Werke und Briefe , edited by Peter Goldammer, vol. 3 (Aufbau Verlag, Berlin and Weimar, 1978), and for the Introduction and Chronology I consulted Peter Staengle’s concise Heinrich von Kleist (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich, 1998), the full biographies by Günter Blamberger (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2011) and Peter Michalzik (List Taschenbuch, Berlin, 2012), and Richard Samuel’s Heinrich von Kleists Teilnahme an den politischen Bewegungen der Jahre 1805–1809 (Kleist-Gedenk- und Forschungstätte, Frankfurt an der Oder, 1995, a translation of a Cambridge thesis completed in 1938 and never published in English). The only biography of Kleist in English is by Joachim Maas of 1977, translated by Ralph Manheim (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1983).

FURTHER READING IN ENGLISH

The most readily available collections of all Kleist stories are The Marquise von O— and Other Stories (Penguin Classics, London, 1978), translated with an Introduction by David Luke and Nigel Reeves, reprinted with Chronology and Further Reading in 2006, and Selected Writings (J. M. Dent, London, 1997), with Introduction, Chronology and Select Bibliography, edited and translated by David Constantine. This contains all the stories, three plays, selections of Kleist’s short, mainly black-humorous anecdotes, three of his philosophical essays and some letters. A larger selection of Kleist’s anecdotes was published in Poetry Nation Review (Manchester, no. 222, 2015), translated by the present translator. An outstanding English-language essay on Kleist is Stephen Vizinczey “The Genius Whose Time Has Come”, in Truth and Lies in Literature (Hamish Hamilton, London, 1986; first published on the bicentenary of Kleist’s birth in The Times , November 1977). See also The Marquise von O— and Other Stories , translated and with an Introduction by Martin Greenberg and Preface by Thomas Mann (New American Library, New York, 1960).

My theory and practice of translation seems to be safety in numbers. Peter Ford and Ellen Farquharson read through my version and made invaluable suggestions, Fred Bridgham (translator of the gravestone epigraph, on p. 19 above) and Antony Wood gave encouragement and John Hibberd advice, but my close collaborator has been Gardis Cramer von Laue. She read the text against the original and made numerous invaluable amendments and corrections. My profound thanks go to her for sharing not only her knowledge of her native German, but also her intricate sense of English. When occasionally at a loss, I turned to the late David Luke’s beautiful, accurate but comparatively free version, whereas in general I found myself trying to stay as close as possible to the original.

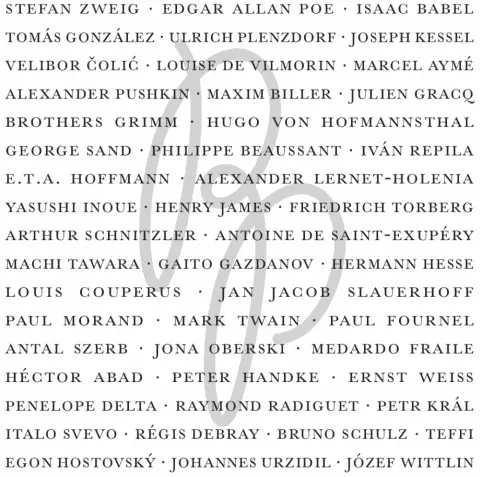

PUSHKIN PRESS

Pushkin Press was founded in 1997, and publishes novels, essays, memoirs, children’s books—everything from timeless classics to the urgent and contemporary.

This book is part of the Pushkin Collection of paperbacks, designed to be as satisfying as possible to hold and to enjoy. It is typeset in Monotype Baskerville, based on the transitional English serif typeface designed in the mid-eighteenth century by John Baskerville. It was lithoprinted on Munken Premium White Paper and notchbound by the independently owned printer TJ International in Padstow, Cornwall. The cover, with French flaps, was printed on Rives Linear Bright White paper. The paper and cover board are both acidfree and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified.

Pushkin Press publishes the best writing from around the world—great stories, beautifully produced, to be read and read again.

Читать дальше

Читать дальше