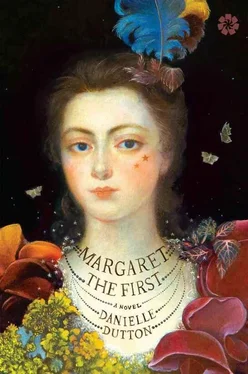

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

PALE YELLOW SPIDERS SPECKED OUR TINY PARISIAN GARDEN— LIKE Cassiopeia on a leaf , I thought, and there is the Harp, the Crab —when one mild afternoon the ambassador came to call. The Scots, he explained, had raised a regiment for the king. Now Prince Charles was off to Rotterdam, to better prepare to return, and the queen wanted William to follow, to help keep her boy secure.

Packing, packing, servants, horses.

I swear, I nearly floated out of town.

Four long years, now free. Free of Paris’s piss-stink alleys and constant doctor visits, its mindless idle gossip and endless gray construction. True, it wasn’t a return to the grassy fields of home, yet travel through the Low Countries afforded golden views: huge sky meeting flattest land, windmills in sunbeams, cows! Each time we approached a town I’d marvel again at the streets — so wide and clean — and masts of boats peeking above a rainbow of Dutch houses.

As our carriages trundled north, and barking dogs and children ran into the lane to watch, I tried to imagine what life would be now: Rotterdam on the Rotte, a port. Beyond that: an empty room. I pulled my cloak around myself. The houses were lit like lanterns. The farmers heading in. I felt a hopeful kind of sadness, driving down that road. I prayed the war would end — in a day, a month, a week — so that we could live at Welbeck Abbey, where I knew he longed to be. I could be a proper wife. Have my sisters to visit. The children in their beds, I thought. Peacocks on the lawn.

But by the time we reached Rotterdam, Prince Charles had disappeared. With money from his brother-in-law he’d put together a fleet. Sail north! Save the king! There was trouble, though: his ship was late, and troops in Scotland refused to march south without him; the battle at Preston easily went to Cromwell.

Yet another battle, in Colchester, my home, was not so simply won. The city was surrounded, the struggle protracted, until one night with roaring drums Parliamentarian forces broke through a Royalist blockade. Fighting ensued at St. John’s Green. The house was destroyed, flattened. Our family vaults were again invaded, but this time it was my sister’s and mother’s coffins the mob defiled. Rings from their fingers stolen, their arms flung into gardens, their legs splashed into the pond. One Royalist report swore Parliamentarian soldiers rode off with the dead ladies’ hair in their hats. Still, the siege lasted another two months. My youngest brother, Charlie, commanded the Royalist forces. The townspeople ate cats and horses. A beggar woman tried to flee and was stabbed at the gates. No one could come out as long as the traitors were in. At last, the Royalists surrendered. Rank-and-file were drawn and quartered. The officers placed themselves at Parliament’s mercy. Charlie was shot in the head.

When word reached Rotterdam, I collapsed on the floor. Since leaving England, I’d lost two brothers, one sister, a niece, and a much-loved mother. My childhood home, the place I’d been happiest — for I was happy then, wandering pastures, picking plums, writing my childish poems, I was happy, I was sure — was gone, my mother’s body strewn across its park. The Lucas clan, once so close-knit, was now completely unraveled, and I had come to believe myself incapable of procreation, of mending those gaping holes with tiny people of my producing. In bed at night I cried out that I was drowning. In that city of water and dams I dreamt of shipwreck every night.

“A damp sponge,” I mumbled.

“All rubble,” I said. “All rubble.”

A doctor came and bled me till I calmed.

~ ~ ~

HE’D BEEN THERE BEFORE — TO VISIT THE RYKERS, HARPSICHORD makers, renowned for the lifelike insects painted on their soundboards — and liked what he had seen: large houses, country estates, superior art collections. Provincial, yes, but affordable, quiet, and she needs to be somewhere quiet , so leaving his wife in the housekeeper’s care, William rode south to Antwerp — fast through browns, through greens, the horizon and the distant city fading into white. All this he later described: how at sundown he stabled his horse, and that night at the inn, over drumsticks with sage, heard the widow of Peter Paul Rubens was looking to let the late painter’s house.

~ ~ ~

IN BLACK BENEATH THE POTTED LIME TREES, AN ARBOR HEAVY WITH roses, I listened as the cathedral with its lacy spire chimed at every hour, south to the reedy countryside, north to the sea, over monasteries with stained glass, over Antwerp’s clean broad streets and the leading publishing house in Europe — printing in Syriac, Hebrew, even musical notes — over lindens and canals and savage-looking orchids. It could have easily fit inside one wing of William’s estate at Welbeck, yet all who saw the Rubens House agreed it was a gem: vaulted windows, colorful frescoes, rooms half-paneled and hung with Flemish leather. He gave me a tortoiseshell cabinet bound with gold, an ebony comb for my hair. He stood in the riotous Renaissance courtyard waving his hat and smiling. I waved back from two floors up, my chamber domed in blue, windows to a columned pavilion, tulips and low hedges.

Eventually, I took to the carriage and established a daily tour: past the East India Company, the Palace of Oosterhuis, boats upon the Scheldt. With fewer people to look at than in Paris, also fewer by whom to be seen, I took pleasure in the rows of tiny shops, the salty air. Here were ladies wearing feathered hats, children eating fried potato in the street. I stopped to watch an Italian troupe perform in the market square. I’d never seen a woman play a man before. How beautiful that lady-husband in her vest and red silk tights, how graceful when she swung her sword and plunged.

Yet some nights I woke with William beside me and thought for a moment he was my dead brother Tom. “Is this me?” I whispered. How did I come to be here? I remembered the tiny shops, the children in the street. All this, I thought in darkness, is temporary. The sun. The salty air. Everything will stop, for me, except myself. I, Margaret, singular, alone. And on he slept.

~ ~ ~

THE KING OF ENGLAND WAS CONVICTED OF TREASON. THEN THE King of England was dead. It was Tuesday. It was 1649. Parliament hacked off Charles I’s head outside the Banqueting House at Whitehall. The mob, previously sick for it, drew quiet after the blow. The people were burdened with heavy taxes. May Day had been replaced by zealous sermons. Was the Civil War now over? Stunned, no one was sure.

~ ~ ~

DAYS LATER THE DEAD KING’S SON — NOW CHARLES II — WAS crowned King of England at The Hague. William stood by him for the oath, then limped south to Antwerp, which I described in a letter to my sister as “the most pleasantest and quietest place to retyre himself and ruin’d fortunes inn.”

ANTWERP, 1649–1651

~ ~ ~

AFTER WINTER CAME SPRING, AFTER SPRING THE HEAT OF SUMMER. William was officially banished, his estates officially seized, and I, officially, was not pregnant. This time they tried, for him, crystals taken from wood ash and dissolved in wine each morning; for me, a tincture of herbs put into my womb at night with a long syringe. I submitted silently, William out in the hall. Come autumn I was to be injected in my rectum with a decoction of flowers one morning, followed by a day-long purge, using rhubarb and pepper, then a day of bleeding, then two days where I took nothing but a julep of ivory, hartshorn, and apple, followed by another purge — and on the seventh day I rested. After this came a week of the steel medicine (steel shavings steeped in wine with fern roots, nephritic wood, apples, and more ivory), described by a maid as “a drench that would poison a horse.” Then summer again: all fizzy spa water and aniseed candies, and motion and rest, in prescribed degrees, and partridge for dinner, or mutton — but never lettuce! — and once a week a bath perfumed with mallows before I slept. If I developed hemorrhoids, I should place leeches on them or be bled from the thigh. And above all else, the doctor said, I must try to be cheerful. No one conceives when sad, he reminded. But I wasn’t sad, exactly, not sad only; I was busy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.