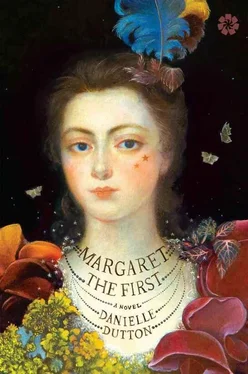

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Danielle Dutton

Margaret the First

For Elijah

Art itself is, for the most part, irregular.

— Margaret CavendishPROLOGUE

THE WOMAN HAD EIGHT CHILDREN. THE FIRST, CALLED TOM, IN 1603, the final year of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. It was five daughters and three sons, and she dressed them richly but simply and cleanly to ward off sharkly habits. Margaret was the youngest. She made the world her book, took a piece of coal and marked a blank white wall. Later, she made sixteen smaller books: untitled, sewn with yarn. Her girlhood heroes were Shakespeare, Ovid, Caesar. She wrote them in beside thinking-rocks and humming-shoes and her favorite sister, Catherine, who starred in all but five. Snow fell fast as she sat by the nursery fire; ink to paper, then she sewed. The last book told a tale of hasty gloom, teeming with many shades of green: emerald, viridian, a mossy black. In it we meet a miniature princess who lives in a seashell castle and sleeps in sheets woven from the eyelids of doves.

For all these fertile inner workings, Margaret was thought plain, couldn’t wear yellow, was shy, yes, seemed younger than her years — yet Margaret longed for fame. When grown, she would adorn herself like a peacock. Or so wrote the diarist Samuel Pepys, whose curiosity brought him out one day to stand along a London road and wait for her carriage to pass. It was May Day and the park was like a circus. “The Duchess of Newcastle is all the pageant now discoursed on”—so he’d written in his diary several weeks before. At breakfast tables and dinner parties, over porridge or pike or a gravy made from the brains of a pig, she was all that anyone talked about, as watched for as Queen Catherine herself but a far more thrilling spectacle: those black stars on her cheeks, the scandal at the theater, her hats! One anonymous satirist had dubbed her Welbeck Abbey’s illustrious whore. Others called her simply fantastical. An overgrown spoilt girl. Her work: chaos. Her books: sad heaps of rubbish. Voluminous, some called her. Crack-brained. So extremely picturesque. Yet there were others, Pepys knew, who considered her the unequaled daughter of the muses and her latest book a blazing utopia to rival Bacon’s own.

He tapped his hat for shade. A crow pecked near his feet. He was about to give it up, and then: “Mad Madge!” someone cried in the street. “Mad Madge!” someone repeated, as her black-and-silver carriage came roaring down the path. But the horses were forced to a stop, for the crowd had grown a mob. “I see her,” someone shouted. He saw her then, through the window glass — black stars, white cheeks. That night in his diary he wrote: “The whole story of this lady is a romance, and everything she does.”

A TRUE RELATION OF MY BIRTH AND BREEDING

COLCHESTER TO OXFORD, 1623–1644

~ ~ ~

leaving london: the busy road before us morphs to gorse and broom, sheep in grass, cottagers spinning and weaving, till Colchester looms at last, its Norman castle high above the crumbling Roman wall, and houses scattered down to the River Colne, the port of the Hythe, the town a full mile from side to side. Colchester — first Camulos, then Camulodunum, some even say it was Camelot — was famous for its eryngoes: roots of sea holly dug up like fingers and candied pink or red. Then just outside the walls: the Lucas estate, St. John’s Green. Once the Abbey of St. John the Baptist, my great-grandfather bought it in 1548 for £132. Dovecotes, farmland, a kitchen garden, cows. Over time it was transformed — from monastery to greathouse, from simple green space to what one visitor would describe as a scene of “rosemary, cut out with curious order, in satyrs, centaurs, whale and half-men-horses and a thousand other counterfeited courses.” In other words, a gentleman’s estate, the relevant gentleman being Thomas Lucas, my father — so this is where I was born.

With its gable tops and chimneys, gatehouse and stables, queens dined at St. John’s Green, where swords and axes shined from walls. Other walls shone with brightly colored silks, windows with damask. Tables were laid with Turkey carpets. And an enormous golden saltcellar stood at the master’s right hand — while a master lived, that is. For poor father died unexpectedly one morning as I, his youngest daughter, toddled the garden path. There’d been a party. My second birthday. Orange ribbons twisting down from trees.

~ ~ ~

AS FOR OUR MOTHER, SHE WAS BEAUTIFUL BEYOND THE RUINS OF TIME. None of her children would be crooked, of course, nor in any ways deformed. Neither were we dwarfish, or of a giantlike stature, but proportional, with brown hair, sound teeth, sweet breath, and tunable voices — not given to wharling in the throat, I mean, or speaking through the nose, unless we had a cold — yet we were none so prone to beauty as she, and I perhaps least of them all. I had no dimples, my mouth was wide, my hair grew crimped and fierce as wild lettuce from my head.

~ ~ ~

A SUMMER AFTERNOON, AGE NINE, SITTING FIRST BENEATH FRENCH honeysuckle, then moving nearer the brook to observe butterflies that gather at pale daffodils, a dead sparrow spotted along the way, and a sonnet begun upon the ability of a sparrow to suffer pain, I, Margaret — Queen of the Tree-people — discovered an invisible world. There, on the surface of the water, river-foam bubbles encased a jubilant cosmos. Whole civilizations lasted for only a moment! Yet from the creation of one of these Bubble-worlds to the moment that world popped into oblivion, the Bubble-people within it fell in love, bore children, and died, their bodies decomposing into a fine foamy substance that was then reintegrated into the foamy infrastructure of the world as the Bubble-children grew up and bore children of their own and died and were integrated into the sky and air and water, and even into the furniture, which was itself a fine foamy substance that the Bubble-folk called “coffee.” In this world, wild horses ran on open fields and sermonized in church on Sundays, speaking always with great eloquence on vast and noble subjects — such as germination — or giving firsthand descriptions of remote landscapes as seen from the eyes of a running horse: the blur of grasses, wind in the nostrils, how a bee will sometimes bump against your forehead.

Standing at the brook that day, creating and destroying this place via the tip of my new leather boot, I began to contemplate all the creatures I had ever killed — innumerable spiders creeping the nursery floor, beetles and slugs in the kitchen garden, a mouse, once, which startled me as I slept — as well as animals I’d ingested or whose skins I had worn on my hands, head, shoulders, and feet: pigs, cows, rabbits, fox, deer, fish, fowl. Was I, Margaret Lucas, responsible for their deaths if I’d had no hand in the slaughter? By bedtime, I’d decided that I was. And I took care the following Sunday to receive a smaller portion of the roast.

“Picky Peg,” my brother teased.

I solemnly chewed my bread.

“Picky Peg,” they laughed.

Then I began to weep, openly, into the soup. It wasn’t their simple teasing; my mood had been strange all day. For tomorrow I’d be sent to London to visit our sister Mary — my first trip away from home! What if the yellow poppies bloomed? What if our mother died?

That night a storm came tearing through our fields. Perched in the nursery window, I saw the lightning fall in liquid streams. A ghostly army of silhouetted trees fought against the sky! I did not sleep, thinking the weather a terrible portent, and was therefore dressed by dawn — long hair in intricate twists — to breakfast in the dining room attended by my nurse.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.