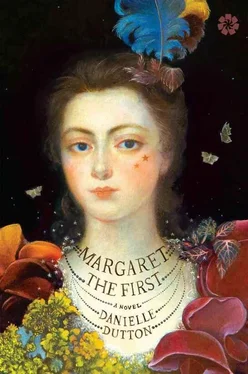

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I had rather be a meteor, singly, alone.”

Plus Paris itself was noisome. Even with its glittering bridges and orangeries, even if the birthplace of ballet.

“I had rather been a meteor, than a star in a crowd.”

There was the humidity, the innumerable crashing coaches, and French aristocrats and servants relieving themselves in the halls. All summer, heaps of shit steamed on the palace steps. I swear I nearly died of the purging flux that August, saved by a powder of opium, pearls, and gold taken in a bread-pill each night before I slept.

O the fever. The dreams!

Yet most of all, I was bored— so bored. Having arrived at the height of history, the very middle of the world, I was shocked to find myself with less to do than when alone in the country back home. Though marbled and with warbling fountains, the Louvre was vast and always cold. As ladies-in-waiting schemed down endless mirrored corridors, the once-luminous queen retreated, weeping, desperate for the baby she’d been forced to leave in England — safe from the perils of our escape. Some days it seemed as if my fever had never broken: the incessant pointless duels, those ghostly caryatids, a monkey in a doublet roaming halls. Too, I’d grown aware of some new flimsiness in my body — stretching out my long thin arms, the skin as light as muslin, as likely to rip or tear. Even weeks after my illness, my face was white as clay. I refused to run, refused to break a sweat. While ladies-in-waiting pranced and spun, gave chase to honking swans, I only sat and watched them from the knotted flower beds, ignored the book in my lap, and recalled the grounds at St. John’s Green: the fields of purpling wild lettuce, the spidery fern-ringed pond.

Then one downcast afternoon, as I approached my shaded bench, I saw a woman, tall even seated, broad-shouldered and tanned, yet elegantly gowned in gray and pearl ropes. It was a peculiarly informal meeting: I simply sat. My stiff skirts brushed that lady’s, and I opened my book in silence. Yet despite this odd behavior, she took pity on a hushed and sighing girl. “My Mary,” she said, pointing to a child amid the topiary shapes, “who was ten this past July.”

Thus, in a tonsured garden, near a wall of autumn roses, it happened that I made a friend — my first. Lady Browne was newly arrived from London, wife of Sir Richard, French ambassador for our king. Soon I was a regular at their home.

~ ~ ~

AT THE EMBASSY FOR SUPPER — QUAIL IN BROTH AND OYSTERS — LADY Browne remembered my father, whom she’d met at Queen Elizabeth’s court. Yet one name only was on the tongue of Sir Richard: William Cavendish, newly made marquess. This gentleman, he reported between oysters, had recently fled to Hamburg after losing badly with a regiment raised near York. A master horseman and fencer, and one of the richest men in England, he wrote plays — oyster — collected viols — oyster—“his particular love in music”—and was by all accounts — oyster — affable and quick. As for official news, the post arrived on Tuesdays. I was sometimes sent to retrieve it from a sympathetic banker in the Rue de Quiquempoit. The queen employed secret couriers for her letters to the king, transported to Oxford in wigs or hollow canes. If apprehended, well, the agents risked death. By now it was clear: the Royalists were losing.

~ ~ ~

AND THOUGH AWKWARD STILL IN THE PRESENCE OF ANY MAN WHO wasn’t a brother, yet I appear in a painting from around this time — of the queen and her exiled ladies — with my neckline plunging deep, as was the mode: I wear a cherry cap, have good plump breasts, fair skin, precise little curls.

~ ~ ~

IN 1645 WILLIAM CAVENDISH ARRIVED IN PARIS IN A COACH PULLED BY nine Holsteiner horses. In truth, the marquess had run out of funds but rightly assumed he’d get better credit if he seemed a less risky investment, so presented himself to the queen and gave her a gift of six of his steeds. Henrietta Maria accepted on the panoramic steps of the Louvre. Ladies-in-waiting in springtime flounces flanked her. William’s seasoned eye lighted on one whose own, this once, looked back. What was that shy girl thinking? That standing in velvet on freshly raked gravel was a version of Shakespeare or Caesar? Here indeed was manly fame and fortune: a playwright and poet, a horseman and soldier, a handsome widower and infamous flirt. But would he ask to meet her, the girl with the quiet stare, sister of one of his captured commanders? There were many unmarried ladies at court: some of them rich, quite a few pretty, each hoping to make a good match. William Cavendish had his pick. He picked me, to wide surprise.

Firstly, he existed in a social sphere far above my own. And I, who rarely spoke, almost never spoke to men. But at thirty years my senior, William knew — unlike noisy young courtiers — how to seduce a strange bright virgin. He watched me in my silence. My reserve? He thought it charming. His attentions made me blush. I could feel his stare as I snuck off with Cymbeline to a corner. “You enjoy reading?” he asked. We walked the courtyard under jealous eyes. He spoke of things that mattered — my brother, books, my home — and had a way of standing, feet spread, so that his brown eyes met my green ones at one level. Then, and wisely, he began to frequent the embassy, where we often met on Sundays, he kneeling beside me, watching my lips move as I prayed. I was to him a new-come bud, so slender and pale. I smelled of roses, or so he said. I turned pink and asked about my brother.

But just as I began to soften, Henrietta Maria up and quit Paris, taking herself and her court to St. Germain-en-Laye. Her summer château boasted grand suites with painted windows and formal gardens descending to the Seine, with canals and cascading fountains and a cove of faux-grottoes home to clacking metal birds, a bejeweled caterpillar, a golden duck that shook its head and quacked. We smuggled letters. Like clockwork, William composed one poem every other day. I was a “spotless virgin, full of love and truth.” My breasts so plump and young. “If living cannot meet,” wrote he,

then let us try

If after death we can; oh let us die!

And I: “I look apon this world as on a deths head for mortificashun, for I see all things subject to allteration and change, and our hopes as if they had takin opium.”

And he:

Sweetest of nature, virtue, you are it;

Serenest judgement, fancy for a wit;

So confidently modest, so discreet,

As lust turns into love, love homage at your feet.

Summer scorched. Fires burned in surrounding fields posting towers of smoke between the château and Paris. But poetry toils, even in such heat. By the end of the summer, William and I were secretly engaged. Unaccustomed, I troubled. William, brave in secrecy, pressed me against a wall, hands working to get under all those skirts. I hurried down the corridor, locked myself in my room. Alone on the bed, I wished my mother borne across the sea, in through the open painted window, standing on the cold stone floor in France, as if by magic. As others lunched in a tent on the grass, I wrote another note, begging he be patient: “If you shod repent sir how unfortunat a woman I shod be; pray consider I have enemyes.”

It was true! A swelling noise arose at court, the ladies in a rage. Some said coy Miss Lucas had played the marquess like a song. Others whispered loudly about his numerous past lovers and a rumored decline in stamina. His closest friends opposed the match. I had no dower, the war having taken my family’s wealth. I was of gentle but unremarkable birth. I was odd, that much was obvious, even to idle courtiers. They made no attempt to hide what they said, and soon a different rumor reached me: that the marquess courted another. Naturally, I panicked. I even began to admire Paris because William was in it: “Shurly, my lord,” I wrote in haste, “I shall be content to be any thing you would have me to be, so I am yours; I rejoyce at nothing mor than your leters.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.