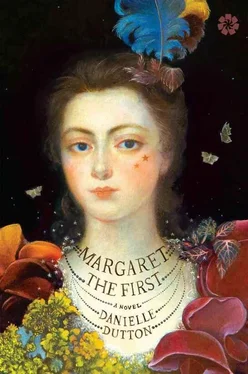

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

PARIS TO ANTWERP, 1646–1649

~ ~ ~

WHEN LONDON INTELLECTUAL JOHN EVELYN MARRIED LADY Browne’s now-twelve-year-old Mary, William and I were among the selected guests. My husband, ever lyrical when it came to virgins, wrote a poem for Evelyn comparing his wife to a horse.

Autumn again, and we attended the opera: Rossi’s Orfeo at the Palais Royale.

At court: there was a masque that Christmas.

On the Pont Neuf: barges on the Seine (do fishes in the river miss the salt of the sea?).

Before a painting: the femme forte , a woman dressed in armor.

In spring, at the ballet: a spectacle of satin.

At the Tuileries: caged tigers lit by torches.

And being fitted: many yards of colored ribbon.

At home: our house was a salon, William a world-class host. He was witty, laughed easily, set everyone at ease. He was, too, I quickly learned, a rather famous patron — of Dryden, Gassendi, Jonson, and more. I greeted with practiced curtsies, grasped a Chinese fan. Here came William Davenant, poet laureate, who’d lost his nose to syphilis and wore a black cloth in its place. Handsome Lord Widdrington, Bishop John Bramhall, Edmund Waller with his fishy eye, Sir Kenelm Digby, and merry Thomas Hobbes. As for the French: René Descartes, Roberval, and the father of acoustics, Marin Mersenne, who stared openly at my breasts.

Of what did they speak as they stood or sat near the fire?

In the beginning they came to eat; William was generous, even when insolvent, and many of the exiles had fled with nothing but their shirts. On the buffet sat wine, cheeses hard and soft, bread, poached apples, berries or asparagus, fish with horseradish, sliced salted ham.

A man from Japan folded paper into frogs.

An Austrian played rondeaux upon the harpsichord.

One evening someone asked what modern scheme would replace the collapsed Aristotelian system, the Middle Ages with their air, wind, earth, and fire, their Ptolemaic structure of the heavens. Soon, beside empty glasses and snuffboxes, strange homemade instruments materialized on our tables: telescopes, compasses, captoptics, more. They spoke of new philosophies, in English or French, of bustling worlds in microscopes, the human body and mind, atomic operations and mechanical arrangement. It was all perfectly new to my thinking. I’d never seen a baro-meter, or cupped a lens in my palm. I sat in the corner, pretending to read or sew.

One especially spirited night, William himself proposed that each star we see is a sun, with planets above and below. “It stands to reason,” he explained, “that the universe is filled with planets we cannot perceive, due to the strength of their suns. Invisible, you see, yet teeming with life.” “Yes, if—” someone started; “No, but—” another broke in. Lively debate ensued, and a newcomer, seeing me listen, asked me for my thoughts. I demurred, claiming my sex as reason. A second man then sportingly suggested they debate the nature of woman. “You will find, sir,” I abruptly spoke, “women as difficult to be known and understood as the universe.” The room fell silent. I was surprised as any man. Madame de La Fayette called the following week.

Indeed I was, for the very first time, totally à la mode . Talk of the place and role of women had been circulating through fashionable salons in each district of the city. Sex a physical distinction, not a quality of mind? A writer, they insisted, must be totally unique. What shape are the atoms at the bottom of the sea? The language of the universe is music. No, math! Hobbes insisted he’d been first to attain a theory of light. Descartes rejected any bodily perception. Someone claimed the right kind of ship might as easily sail up as east. You cannot move from “I am thinking” to “I am thought.” Passions flared. William stood in the middle, attempting to keep peace. I listened from my chair or upstairs in my room. As quickly as I’d entered their conversation, I slipped out of it again. My mind, I often felt, was like a little cave of mud. I never spoke to Master Hobbes, said nothing to Descartes. In fact — William couldn’t fail to notice — his wife spoke less and less.

In March, in London, my niece died from consumption. In April, my sister Mary. In Ireland that summer my brother Tom was crushed by his horse. The following autumn, our mother was taken.

Alone in my room in Paris, I felt oblivion creep near.

I wrote: “Mother liv’d to see the ruin of her Childrin in which was her ruin and then died.”

I wrote: “I did a silent mourning Beautie spy.”

~ ~ ~

TWO YEARS OF MARRIAGE PASSED AND STILL I WAS NOT PREGNANT. Remedies were prescribed, everything from more rest to the excrement of a virile ram rubbed across my belly. The king’s own doctor, Sir Theodore Mayerne, wrote to William from London: Was the marquess aware that a woman could not conceive without an excited swelling, a heat? Of what frequency and duration was my ardor? A French doctor insisted that William need only lift my spirits, for a woman cannot get pregnant if she is always sad. I had taken to regular vomits, refused to come out of mourning, refused the doctor’s tinctures, which gave me terrible gas. Yes, I was often quiet, as the doctor had observed. But my husband chose not to worry. That summer I turned twenty-four.

Then William’s son Henry died. Or, he nearly died. He lay near death in England. Letters rushed to Paris, each contradicting the others. His doctors flushed him with gold and mercury. They dusted powdered frog on his meat at every meal. Still, he worsened.

William troubled in the garden. He troubled atop his horse.

And though Henry was only a second son, I was under an ever-increasing pressure to produce. Each night we tried again. Each morning I asked for the carriage and made the daily tour: down the expansive Cour de la Reine, seeing all of fashionable Paris without, myself, being seen.

Bien sûr , they knew I was in there. I was Margaret Cavendish, marchioness, hiding in her carriage.

Yet as Paris whispered of my failure, my husband, over fifty, was buying tonic on the sly: one for elevating , made of the backbones of vipers, to be taken half-a-dram each day dissolved in broth. That same French doctor urged mutton dressed with new-laid eggs and a little nutmeg or amber. He advised my husband to anoint his big toes in Spanish oil each night.

On top of all this, our money was gone. Parisian creditors were anxious and would not provide: no meat, no wine, no wax. I was tormented by worries William would be thrown in debtor’s jail. Fortunately, the queen, conscious of an obligation, finally repaid a sizable loan that William had made her in Yorkshire. He promptly bought two Barbary horses, one telescope from Torricelli, and four from Divini’s shop. “More important than baguette,” he said, “is to maintain the appearance of means.” In the mornings I stood in a nearby grove, thinking of my dead mother, transfixed by the peeling bark. Each night we tried again. Each day I called for the carriage. The crowds. The doctor came. Then a letter arrived from London with news that Henry had recovered, was up out of his bed. Still, I felt more suited to sitting on graves than dancing at Christmas balls. Invitations came, but I turned them down. At New Year’s William’s telescopes reached us in boxes packed with straw. There was even one for me, in fine marbled paper, a gift. “My Lady’s Multiplying Glass,” he said, and taught me how to hold it up a breath away from my eye.

Thus as a family — frustrated, gassy, impotent, poor — we wondered together at the turning of the stars.

~ ~ ~

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.