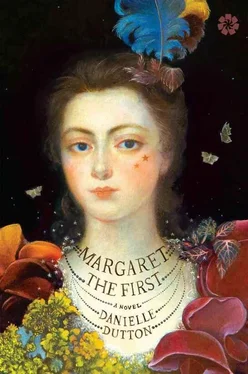

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Of Aiery Atomes.”

“On a Melting Beauty.”

“Similizing Thoughts.”

“Thoughts,” I wrote, “as a Pen do write upon the Braine.”

I drew a glittering fairy realm at the center of the earth, its singing gnats and colored lamps. I would not leave the house.

Rumors swirled. Servants talk, of course. The floorboards creaked as I paced and spoke alone. The hallway went sharp with the scent of burning ink. Did I cook up incantations? They sounded half afraid. Pacing, yes, reciting my favorite lines. My mind was elsewhere, halfway to the moon. If atoms are so small, why not worlds inside our own? A world inside a peach pit? Inside a ball of snow? And so I conjured one inside a lady’s earring, where seasons pass, and life and death, without the lady’s hearing.

Of course, there were moments I faltered, fell suddenly into doubt. I’d never been taught, after all, and knew so little the rules of grammar. I’d embarrass myself, the family. I warmed my hands before the fire. Took up a fork and put it down. A woman on the street sang bleak hymns on the corner. Yet why must grammar be like a prison for the mind? Might not language be as a closet full of gowns? Of a generally similar cut, with a hole for the head and neck to pass, but filled with difference and a variety of trimmings so that we don’t grow bored?

Then I took it a step too far: I would put forth.

~ ~ ~

THOUGH THERE WAS SCANTY PRECEDENT FOR WHAT I WAS ABOUT TO do, I hurriedly packed my papers and set out to St. Paul’s churchyard, to the foremost publisher in England: Martin & Allestyre, at the Sign of the Bell.

An oddity from an odd marchioness? They snapped it up.

It would be public. It was done. I’d breathed no word to William and bade the publishers hold their tongue. I’d return to Antwerp shortly. I would rather seek pardon there than ask permission first.

LONDON TO ANTWERP, 1653–1656

~ ~ ~

ONE WOMAN WROTE TO HER FIANCÉ IN LONDON: “IF YOU MEET WITH Poems & Fancies , send it me; they say ’tis ten times more extravagant than her dress.” Then a week later followed that note with another: “You need not send me my Lady’s book at all, for I have seen it, and am satisfied that there are many soberer people in Bedlam.” But oddity is fodder for talk, and my book was soon required reading in London’s most fashionable parlors. “Passionitt,” they sniggered — it seems my spelling did astonish—“sattisfackson,” “descouersce” for “discourse,” even “Quine” for “Queen.” Happily, I was already aboard a fourth-rate frigate bound for Antwerp. I saw a double rainbow, a porpoise in the waves. And when I arrived back home? William was astonished, yes, but not in the way I’d feared. He was proud. Far from being angry over the cost the printing incurred, he took it upon himself to send copies to his many and illustrious acquaintances. “It is a favor few husbands would grant their wives,” I said, relieved, and this was true. Then the tidal wave of gossip arrived in the mail.

I set down a letter from William’s daughter Jane. “It is against nature for a woman to spell right,” I bristled. William only kissed my cheek. “Such ill-informed, seditious readers,” he calmly said, “should exist beneath a marchioness’s notice.”

January, February, March.

One anonymous critic claimed that when he read Poems & Fancies his stomach began to rise — for Jane saw fit to send each notice the book incurred. Some readers were cross a lady had published at all, others that she had written of vacuums and war, rather than poems of love. William ignored the talk. He fenced and rode horses when the fashion was pall-mall. Still, I felt rotten, felt low. I hid and wished, or nearly wished, I had not published at all. I completely avoided the cabinet where my earlier writings lay. The days were short and dull, the garden in its thaw. Antwerp’s blue-gray cobblestones went slick with rain and moss.

At last a mild evening: we took our supper outside, the leaves still off the branches, the stars so clear in the sky. Over pigeon pie and cherry compote, we spoke of his new horse. When I set aside my fork, William produced a note. “A letter has come from Huygens,” he said, “who’s been traveling in the south.” He turned a page and read: “It is a wonderful book, whose extravagant atoms kept me from sleeping last night.” The blood whirred inside my head. “What’s this?” I managed to say. Here was a letter from Huygens — who mattered! — Huygens, who’d read my book. I could hardly hear the rest as William read aloud: something, something, something, vibrating strings, my book!

Thus by the time the spotted tulips blossomed, the nastiness of London seemed far across the sea. Indeed, it was a lovely spring. The sky was in the pond, the larks above. I tried to name each of the flowers we saw: double violet, lily, double black violet, plum.

William left Antwerp for a hunting trip in the Hoogstraten.

I, at last, unlocked the cabinet in my room.

~ ~ ~

THERE LAY EVERYTHING I’D WRITTEN BEFORE BEING SENT TO London: essays, puzzles, anecdotes, rhymes. Did I expect a trove of gems? I found some worthy ideas, but no structure to the mess. Still, it had to work — it must! — for there is more pleasure in making than mending, I thought, and I named it after an olio, a spicy Spanish stew (a pinch of this, dash of that, onions, pumpkin, cabbage, beef), sitting to pen a defensive preface: “This is to let you know, that I know, my Book is neither wise, witty, nor methodical, but various and extravagant, for I have not tyed myself to any one Opinion, for sometimes one Opinion crosses another; and in so doing, I do as most several Writers do; onely they contradict one and another, and I contradict, or rather please my self, since it is said there is nothing truly known .”

Reading it back, I realized I believed it.

I was busy with two new pieces when a letter arrived in the mail: in the rented house in London, Sir Charles was stricken by ague. A week later, dear Charles was dead. William, just returned from the hunt, fell suddenly ill at the shock.

I split my days, so split myself: it was mornings with my husband, afternoons at my desk. My thoughts spun round, like fireworks, or rather stars, set thick upon the brain. Truly I mourned Charles, yet every afternoon I lit up like a torch. In one essay I called the Parliamentarians demons. Gold mines, I argued, could not be formed by the sun. My fingernails went black from the scraping of my quill. Few friends came to the house. Had I lost what friends we’d made? It was one thing to write riddles for ladies, another to do what I’d done.

Still, the summer invitations would arrive.

And so: at a soiree at the Duartes’ I sat in black between Mr. Duarte and a visitor from Rome. I’d come alone — William too ill to attend — and grew sleepy on French wine as the two men spoke Italian across my chest all night. Finally, over boiled berry pudding, the Duartes announced a surprise: their eldest girl was pregnant, the pretty one who’d sung like a bird, now resting with her hands across her belly in a chair. Everyone raised a glass. I raised a glass. I looked around me, sipped the wine. To many healthy babies, I agreed. Yet I sank down into a private wordless rage, the fury of which I could not explain. I ordered the carriage, returned to the house. When William asked how the evening had gone, I snapped. Surely I had no time for such silly affectation. Only my work and my sick husband mattered. Nor was it easy labor. How many pages a day? How many days? Until, in the first fine week of autumn, as the branches in the orchard bent and wasps went mad with fruit, I set aside my quill. I’d finished my second book.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.