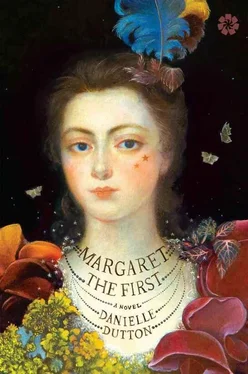

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

So, a carrying on of patterns: in and out of rooms, watching windows, imperceptibly closing doors. When the night of Béatrix’s party arrived, William was dressed as a captain. I emerged from the marble staircase in layers of gauze and yellow silk. “A beehive?” he asked, and offered me his arm.

Birds still chirped in branches. The night was warm, bright with moonlight and the lanterns off carriages that lined the gravel drive. Once inside the castle, William wandered left, I right, glancing through rooms, over tables lit by tulips, and out the windows to stars. In elaborate gilded bird-beak masks, partygoers passed me. Even the music was like a dream, a foreign, pulsing air. And there, in the bustling courtyard, I spotted her at last — Christina, Queen of Sweden. She was dressed as an Amazon. Her entire breasts were bared, her knees. O excellent scandal! O clever ladies’ chatter! But privately I admired the queen’s gold helmet and cape, and her hand that rested lightly on the hilt of her handsome sword.

The following morning, a messenger rang the bell. William was out atop a horse, so I received the note. The widow was not pregnant. I asked the cook to fix his favorite meal. Over a pie of eels and oysters, I gently broke the news. “It will all be for the best,” I said. I didn’t say it might be best for the widow as well. I didn’t say: There’s no telling a child will be any comfort to its mother at all.

~ ~ ~

WHEN THE SCHELDT FROZE THIS TIME, I STOOD AT THE WINDOW, watching Antwerp’s well-to-do slide by. Their sleighs, gliding, were lit by footmen with torches. William easily persuaded me to go out. Bundled in blankets, we rode to the shore, to revelers skating, vendors selling cakes and fried potatoes under lamps. The frozen expanse glistened in the dark, icicles licking the pier like devil’s tongues. William stepped down and waited for me to follow. And — oh! — how I longed to go, to dance with him on incorporeal legs. But I couldn’t. Or I wouldn’t. He climbed back up. We turned around. William looked strangely heartbroken, and we rode through the streets in silence. Then alone at my desk, I imagined a frozen river in me: “a smooth glassy ice, whereupon my thoughts are sliding.”

ANTWERP TO THE CHANNEL, 1658–1660

~ ~ ~

WHEN YOUNG KING CHARLES II CAME FROM PARIS TO VISIT HIS brothers (the dukes) and sister (now Princess of Orange), William proposed a ball: “Opulent, of course, yet fittingly refined.” We stuffed Delft bowls with winter roses — their petals tissue-thin — and draped the painter’s studio in silk. Dancing was of the English country style, with arched arms and curtsies, embroidered twists and knots. “Lavish,” it was whispered. And sixteen hired servants carried dinner on eight enormous silver chargers — half through the eastern door, half through the west, meeting at a table in the center of the room. I managed the evening from a confluence of my own, a merging of myself, my present and my past, as if half of myself were here, myself, while the other half was still in Oxford clutching the queen’s fox train. Back then I’d been but a maid — and awkward and shy — whereas tonight I was a marchioness and seated beside the king. “Did you know,” he leaned in close, “you are something of a celebrity in London?” In truth, I’d heard as much. Still, I blushed as pink as the ham. “And it seems your husband’s credit,” he winked, “can procure better meat than my own.” At two in the morning, we toasted the Commonwealth’s downfall. And seven months later, by God’s blessing, Cromwell was dead.

~ ~ ~

WILLIAM WAS HUNTING IN THE HOOGSTRATEN WHEN THE NEWS hit. In Paris, Rotterdam, Calais, Antwerp, exiles danced in the street.

Cromwell was dead.

I was at my desk.

Then, a creeping kind of peace. For some months nothing happened. There were skirmishes, flare-ups, but nothing of any substance. Not until December of the following year was William confident of a speedy restoration. He began, in delight, to compile a book of counsel, to be handed to the young king at some sympathetic moment. “Monopolies must be abolished,” he wrote. “Acorns should be planted throughout the land.” But above all else — and here he was firm — the king must circulate, must be as a god in splendor, and make the people love him “in fear and trembling love,” as they once loved Queen Elizabeth, for “of a Sunday when she opened the window the people would cry, ‘Oh Lord, I saw her hand, I saw her hand.’ ”

He could not wait to be home.

But what could home mean now? To what did we return? Through my open bedroom window came the sounds of morning: the clip-clop of a horse’s hooves, the steady hum of bees. I’d lived in exile half my life, in marriage nearly as long. There was the familiar wooden gate, the leafy garden path. Once, it’s true, I’d wished the war would end, so we could live at Welbeck, where I knew William longed to be. The children in their beds, I’d thought, peacocks on the lawn. But the war had never ended, or it had not ended for us. I’d long ago stopped waiting for home to come.

Still, the king’s words were never far from my mind. A celebrity, he’d said.

Now William finished his book of counsel and had it bound in silk.

I ordered two new gowns: one white and triumphant like a lighthouse, one bruised like autumn fruit.

~ ~ ~

FIREWORKS, SPEECHES, GUN SALUTES, A BALL. IN APRIL OF 1660, THE Hague celebrated with King Charles II. William rushed to his side. He hoped to be named Master of the Horse, but his reception was cool, the little book went unmentioned, and that post of honor was granted to a handsome new courtier named Monck. Snubbed — even as Marmaduke was made a baron, Lord Jermyn an earl — William refused an invitation to join the king’s brother on the crossing, hired an old rotten frigate, and left alone the following day. He never returned to Antwerp. He sent a letter instructing me to remain where I was, a pawn for all his debts. His trip took an endless week — they were becalmed in the middle of the passage — but when finally he saw the smoke and spires of London, his anger passed to joy. He said: “Surely, I have been sixteen years asleep.”

~ ~ ~

ALONE IN MY ROOM, I WAS WRITING PLAYS. THEY WERE ALL-FEMALE plays for an all-female troupe. Of course, it was absurd. Women so rarely acted in public. Of course, I never meant them to be staged. “They will be acted,” I said to no one, “only on the page, only in the mind. My modest closet plays.” I smiled. I dipped my quill in ink.

The housekeeper knocked and held out a note. I took up William’s instructions from the ornate pewter tray.

No more to be done, yet everything to do.

Flemish tapestries, drawing tables, lenses, the telescopes from Paris, books, of course, and perfumes, platters, ewers, ruffs, tinctures, copperplates, saddles, wax. There were little green-patterned moths dashing around the attic, bumping at the glass. I thought I felt like that. I dreamed the moths crept upside down on the surface of my mind. In the mornings I met with a magistrate or bid a neighbor farewell. I myself packed linen-wrapped manuscripts into crates. The plays had a box to share, each handwritten folio tied with purple ribbon: in Bell in Campo , the Kingdom of Restoration and the Kingdom of Faction prepare to go to war, and the wives, with Lady Victoria at their helm, insist on joining the battle; in The Matrimonial Trouble , a housemaid who has married the master proceeds to put on airs; in The Convent of Pleasure —the only not quite finished — Lady Happy, besieged by men who wish to marry her fortune, escapes to a cloister. But the pesky men sneak in, dressed like women, to join the ladies’ play within the walls. Enter Monsieur Take-pleasure and his Man Dick.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.