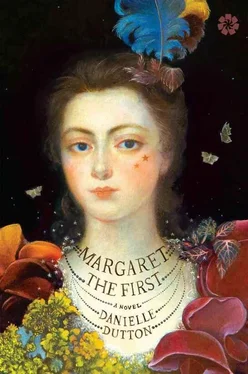

Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Danielle Dutton - Margaret the First» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Catapult, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Margaret the First

- Автор:

- Издательство:Catapult

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Margaret the First: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Margaret the First»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Margaret the First — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Margaret the First», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was Michaelmas and William was recovered.

Now I myself fell ill.

William wrote to Mayerne that I was bilious, passed a great amount of urine with specks of white crystals in it. The doctor wrote back: “Her ladyship’s occupation in writing of books is absolutely bad for health!” And what if it truly was? But if anything, I insisted, I’d only just begun, was off, at last, and thirty- one. I might be praised, I might be censured, but my desire was such, I explained, it was such. but I could not find the words. Judiciously, steadily, William worked to get me out — from my bed, my room, the house — and for his sake, I rallied. I promised him I’d lead a more sensible life.

Of course, by this time my manuscript was already off to London.

So one night, returning from a circus — monsters, camels, baboons, a man with sticks for fingers, a woman with soft brown fur — we opened the door to The World’s Olio arrived in the publisher’s crates.

~ ~ ~

WHILE ONE BOOK IN THE WORLD MIGHT BE CONSIDERED AN anomaly, two books, it seemed, sounded an alarm. The lady is a fraud! Even if the books were ridiculous , how could a woman speak the language of philosophy at all ? I hadn’t attended university. They knew I didn’t read Latin. It fell to reason a man was behind my work — writing it, dictating it, or even perhaps unknowingly the victim of my theft.

But hadn’t Shakespeare written with natural ability?

Every tree a teacher, every bird?

Alone in my room, I fought with the air: “If any thinks my book so well wrote as that I had not the wit to do it, truly I am glad for my wit’s sake!”

~ ~ ~

DEFENDING A SECOND BOOK QUICKLY LED TO A THIRD. Philosophical and Physical Opinions , 1655. In it I argued all matter can think: a woman, a river, a bird. There is no creature or part of nature without innate sense and reason, I wrote, for observe the way a crystal spreads, or how a flower makes way for its seed. I shared each page with William, often before the ink had dried. It put me at odds, he explained, with the prevailing thought of the day. But how could the world be wound up like a clock? It was pulsing, contracting, attracting, and generating infinite forms of knowledge. Nor could man’s be supreme. For how could there be any supreme knowledge in such an animate system? One critic called the book a “vile performance.” But another said my writing proved the mind is without a sex!

At dinner parties now, I was sometimes asked to account for myself, to speak of my ideas. I very rarely could. Bold on the page, in life I was only Margaret.

Still, Antwerp, the parties, my husband’s talks — all of it fed my mind. I’d hardly set down my quill before I took it up again, writing stories unconnected — of a pimp, a virgin, a rogue — strung up like pearls on a thread. This one, my fourth, called Natures Pictures , was something of a hit. It opens with a scene of family life — men blowing noses, humble women in rustling skirts — and closes somewhat less humbly, I admit, with “A True Relation of My Birth, Breeding, and Life”—in which, for the sake of history, I describe in my own words my childhood in Essex, my experiences of war, my marriage and disposition — in short, my life — and ultimately declare: “I am very ambitious, yet ’tis neither for Beauty, Wit, Titles, Wealth or Power, but as they are steps to raise me to Fames Tower.” O minor victory! O small delight! My star began to rise.

ANTWERP, 1657

~ ~ ~

I PAUSED IN THE HALL BEFORE GOING IN TO EAT. “I’VE HAD IT,” William spat, “with this damned unending war.” I took a spoonful of chestnut soup. “Yes,” I said, and watched him as he chewed. He finished his dinner in silence, hulked off to his room. Alone with the duck and a vase of roses, was I to blame for his mood? The latest round of gossip had rattled him, I knew. “Here’s the crime,” he’d said in a fit, “a lady writes it, and to entrench so much upon the male prerogative is not to be forgiven!” He’d defended me at every turn. Yet lately he’d been riled. And for my part — riled, too — I decided simply to busy myself with the summer as best I could.

There was a housekeeper to hire.

A neighbor starting an archery school on the opposite side of our fence.

A portrait to sit for — or rather, I stood.

And Christina, Queen of Sweden, was on a European tour.

Of course I’d heard the stories, impossible to avoid: how the queen drew crowds in Frankfurt and Paris, where one lady, shocked, wrote that her “voice and actions are altogether masculine,” noted her “masculine haughty mien,” and bemoaned a lack of “that modesty which is so becoming, and indeed necessary, in our sex.” She wore breeches, doublets, even men’s shoes. She smoked. She’d sacked Prague. She wore a short periwig over her own flaxen braids, and a black cap, which she swept off her head whenever a lady approached. Most importantly, she’d be traveling to Antwerp next, and Béatrix in her castle would host a masquerade.

A Gypsy, a flame, a sea nymph? I wondered what to be.

Late one night, with the ball still weeks away, a messenger banged on our door. Voices from the courtyard, footsteps down the hall — I found William in the parlor and a letter on the floor. The Viscount of Mansfield, Charles Cavendish, Charlie, his eldest, was dead. A “palsy” was how the letter writer put it: raised a glass to his lips and choked on the lamb. “Inconceivable,” William choked. He muttered to himself. Only thirty-three and alive last week. I reached out for his hand. Was there anything he needed? But he didn’t see that the fire smoked. He didn’t hear me leave. I stepped into the courtyard, where out under the whirling stars I prayed for a grandson, many grandsons, legions of grandsons for William, who sat in front of the fire with the blankest of looks on his face. I watched him through the windowpane as through a room of glass. Later, too — tossing, restless — I watched as if from another world as he sweated through his sheets. He took a glass of brandy. He drifted off at last.

Next came a flurry of letters, back and forth. William grew suspicious, suspected the widow — of what? And Henry, so long a second son, was quick to claim his dead brother’s title, even as his sisters begged him to delay, ensure that Charlie’s widow wasn’t pregnant with an heir. William shouted at servants. He fired the cook, rang the bell. Meanwhile, feeling so far from my husband’s grieving, I felt strangely aware of myself. My face in the mirror was only one year older than Charlie’s had been last week. How odd that I could still feel like a girl, be made to feel it, feel the cold floors of St. John’s Green beneath my feet—“Picky Peg,” my brothers called me — yet my neck was beginning to sag, the skin grown soft and loose. I was all discontent. Angry, in fact. At Charlie for dying so suddenly, at Henry for causing William to suffer, at William for letting his children upset him as much as they did.

A week passed with hardly a word in the house.

I worked at poems, he on his book about manège .

At last, one night, he asked me to sit up with him, and I agreed to a small glass of wine. We settled on a sofa near the fire. A quiet rain was falling. A dog in the corner scratched. My husband began to cry. “Now my best hope is that his widow will be pregnant.” He choked back a sob. “A link to poor Charlie,” he sighed. He took out a handkerchief, blew his nose: “Of course, I do not blame you.” I put down the glass of wine. “Blame me for what?” I asked. He fiddled with a ring. “I will never hold our disappointment against you,” he finally said. His words, though softly spoken, meant, I saw, he did.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Margaret the First»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Margaret the First» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Margaret the First» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.