Ursula K. Le Guin

LAVINIA

sola domum et tantas servabat filia sedes,

iam matura viro, iam plenis nubilis annis.

multi illam magno e Latio totaque petebant

Ausonia…

A single daughter, now ripe for a man,

now of full marriageable age, kept the great

household. Many from broad Latium and

all Ausonia came wooing her…

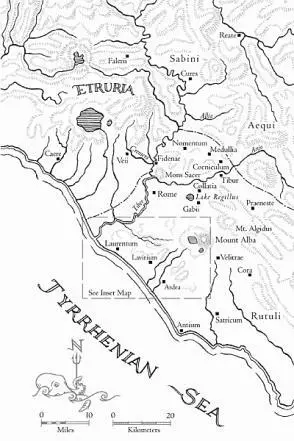

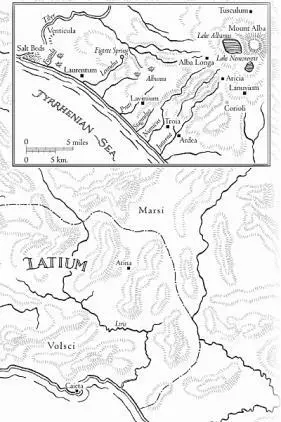

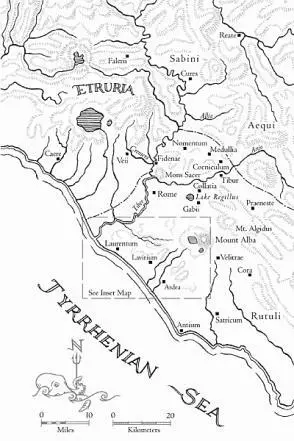

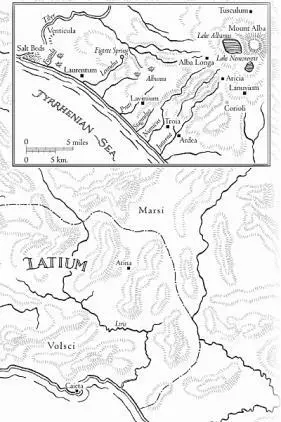

I went to the salt beds by the mouth of the river, in the May of my nineteenth year, to get salt for the sacred meal. Tita and Maruna came with me, and my father sent an old house slave and a boy with a donkey to carry the salt home. It’s only a few miles up the coast, but we made an overnight picnic of it, loading the poor little donkey with food, taking all day to get there, setting up camp on a grassy dune above the beaches of the river and the sea. The five of us had supper round the fire, and told stories and sang songs while the sun set in the sea and the May dusk turned blue and bluer. Then we slept under the seawind.

I woke at the first beginning of light. The others were sound asleep. The birds were just beginning their dawn chorus. I got up and went down to the mouth of the river. I dipped up a little water and let it fall back as offering before I drank, saying the river’s name, Tiber, Father Tiber, and his old, secret names as well, Albu, Rumon. Then I drank, liking the half-salt taste of the water. The sky was light enough now that I could see the long, stiff waves at the bar where the current met the incoming tide.

Out beyond that, on the dim sea I saw ships—a line of great, black ships, coming up from the south and wheeling and heading in to the river mouth. On each side of each ship a long rank of oars lifted and beat like the beat of wings in the twilight.

One after another the ships breasted the waves at the bar, rising and plunging, one after another they came straight on. Their long, arched, triple beaks were bronze. I crouched by the waterside in the salty mud. The first ship entered the river and came past me, dark above me, moving steadily to the heavy soft beat of the oars on the water. The faces of the oarsmen were shadowed but a man stood up against the sky on the high stern of the ship, gazing ahead.

His face is stern yet unguarded; he is looking ahead into the darkness, praying. I know who he is.

By the time the last of the ships passed by me with that soft, labored beat and rush of oars and vanished into the forest that grows thick on both banks, the birds were singing aloud everywhere and the sky was bright above the eastern hills. I climbed back up to our camp. No one was awake; the ships had passed them in their sleep. I said nothing to them of what I had seen. We went down to the salt pans and dug up enough of the muddy grey stuff to make salt for the year’s use, loaded it in the donkey’s baskets, and set off home. I did not let them linger, and they complained and dawdled a little, but we were home well before noon.

I went to the king and said, “A great fleet of warships went up the river at dawn, father.” He looked at me; his face was sad. “So soon,” was all he said.

I know who I was, I can tell you who I may have been, but I am, now, only in this line of words I write. I’m not sure of the nature of my existence, and wonder to find myself writing. I speak Latin, of course, but did I ever learn to write it? That seems unlikely. No doubt someone with my name, Lavinia, did exist, but she may have been so different from my own idea of myself, or my poet’s idea of me, that it only confuses me to think about her. As far as I know, it was my poet who gave me any reality at all. Before he wrote, I was the mistiest of figures, scarcely more than a name in a genealogy. It was he who brought me to life, to myself, and so made me able to remember my life and myself, which I do, vividly, with all kinds of emotions, emotions I feel strongly as I write, perhaps because the events I remember only come to exist as I write them, or as he wrote them.

But he did not write them. He slighted my life, in his poem. He scanted me, because he only came to know who I was when he was dying. He’s not to blame. It was too late for him to make amends, rethink, complete the half lines, perfect the poem he thought imperfect. He grieved for that, I know; he grieved for me. Perhaps where he is now, down there across the dark rivers, somebody will tell him that Lavinia grieves for him.

I won’t die. Of that I am all but certain. My life is too contingent to lead to anything so absolute as death. I have not enough real mortality. No doubt I will eventually fade away and be lost in oblivion, as I would have done long ago if the poet hadn’t summoned me into existence. Perhaps I will become a false dream clinging like a bat to the underside of the leaves of the tree at the gate of the underworld, or an owl flitting in the dark oaks of Albunea. But I won’t have to tear myself from life and go down into the dark, as he did, poor man, first in his imagination, and then as his own ghost. We each have to endure our own afterlife, he said to me once, or that is one way to understand what he said. But that dim loitering about, down in the underworld, waiting to be forgotten or reborn—that isn’t true being, not even half true as my being is as I write and you read it, and nowhere near as true as in his words, the splendid, vivid words I’ve lived in for centuries.

And yet my part of them, the life he gave me in his poem, is so dull, except for the one moment when my hair catches fire—so colorless, except when my maiden cheeks blush like ivory stained with crimson dye—so conventional, I can’t bear it any longer. If I must go on existing century after century, then once at least I must break out and speak. He didn’t let me say a word. I have to take the word from him. He gave me a long life but a small one. I need room, I need air. My soul reaches out into the old forests of my Italy, up to the sunlit hills, up to the winds of the swan and the truth-speaking crow. My mother was mad, but I was not. My father was old, but I was young. Like Spartan Helen, I caused a war. She caused hers by letting men who wanted her take her. I caused mine because I wouldn’t be given, wouldn’t be taken, but chose my man and my fate. The man was famous, the fate obscure; not a bad balance.

All the same, sometimes I believe I must be long dead, and am telling this story in some part of the underworld that we didn’t know about—a deceiving place where we think we’re alive, where we think we’re growing old and remembering what happened when we were young, when the bees swarmed and my hair caught fire, when the Trojans came. After all, how can it be that we can all talk to one another? I remember the foreigners from the other side of the world, sailing up the Tiber into a country they knew nothing of: their envoy came to my father’s house, explained that he was a Trojan, and made polite speeches in fluent Latin. Now how could that be? Do we all know all the languages? That can be true only of the dead, whose land lies under all the other lands. How is it that you understand me, who lived twenty-five or thirty centuries ago? Do you know Latin?

But then I think no, it has nothing to do with being dead, it’s not death that allows us to understand one another, but poetry.

If you’d met me when I was a girl at home you might well have thought that my poet’s faint portrait of me, sketched as if with a brass pin on a wax tablet, was quite sufficient: a girl, a king’s daughter, a marriageable virgin, chaste, silent, obedient, ready to a man’s will as a field in spring is ready for the plow.

Читать дальше