Two months later I landed at Cuyahoga County Airport, Cleveland, and taxied to the American Aviation factory, with its pond of bright-painted Yankees awaiting delivery. And out across the ramp came Bo Beaven to meet me. He wore white shirt and tie, to be sure, but it was not the businessman Frank, it was my friend. There were just bits of the Frank-mask left about him, bits that Bo had allowed to remain because they served a purpose in his job. But the man who had been walled away from the sky was now alive and well and in full charge of the body.

“You wouldn’t have any of these planes to deliver east, would you?” I said. “Maybe you and I could ferry one out.”

“Who’s to say? We just might have one to go.” He said it with a perfectly straight face.

His office now is the office of the Director of Purchasing, a mildly cluttered place with a window overlooking the factory floor. There on a filing cabinet stands a scratched and battered company model of an F-100, pitot boom missing, decal shredded, but proud and there, banking into the indoor sky. On the wall is a photograph of a pair of Yankees in formation over the Nevada desert. “That look familiar?” he asked shortly. I didn’t know whether he meant the desert or the formation. They were both familiar, to me and to Bo; the businessman Frank had never seen either one.

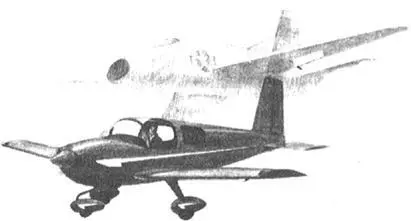

He showed me around the Yankee plant, at ease in this place where the seamless sport plane comes to life out of metal as he had come to life out of grounded flesh. He talked about the way the Yankee is bonded together instead of riveted, about the strength of the honeycomb cabin section, about problems in sheet planning and the shape of a control wheel. Technical business talk, for sure, but the business now was airplanes.

“All right, fella. What was it like, what has it really been like for you, the last ten years?” I said, relaxing in the car while he watched the road home carefully, not looking at me.

“I used to think about it,” he said slowly, “the first year out of flying, wandering to work in the morning when there was a bit of cloudiness. I’d think of the sun, up on top. It was awfully hard.” He took the turns fast, keeping his eyes on the road. “The first year was bad. But by the end of the second year, I almost never thought about it; but occasionally I would maybe in the corner of my ear hear an airplane above an overcast or something, and give some thought. Or maybe for business reasons I’d take a commercial flight to Chicago and have occasion to go on top, and then I’d remember all these things. ‘Yes, I used to do this frequently, that was fun, that was enjoyable, that made you feel clean and all that sort of stuff.’ But then I’d land, get to the business of the day, and maybe sleep on the way back, and I wouldn’t have that thought, I wouldn’t think of it tomorrow, or the next day.”

Tree-shadows flickered over the car. “I was unhappy, with that company. It had no relation to a product that I knew about or was interested in. I didn’t care if they ever sold another wringer washer or another ton of reclaimed rubber or another carload of diaper pails. I didn’t care at all.”

We stopped at his house, a white-painted lawn-surrounded picket-fence place in the shade of Maple Street, Chagrin Falls, Ohio. It was a moment before he left the car.

“Don’t get me wrong, now. I don’t think that at any time, other than just flying alone, tooling around, did I ever give any thought to things like breaking through the overcast. When I saw the sun, it was what I expected to see. It was very nice, pleasant to see all the clean tops-of-clouds where underneath there were all the dirty bottoms-of-clouds. But I don’t think I had any lofty godly-type thoughts when I was flying, that sort of thing.

“It might have been very casual, I might have broken out and said mentally, ‘Well, God, here I am up here looking at it the way you’re looking at it.’ And God would say, ‘Roj,’ and that’d be all there was to that. Or he’d click his mike button to acknowledge that I had spoken.

“I was always awe-stricken at how much there was of the top of clouds. And the fact that I was up there, tooling around with the bigness of it all, skirting a big thunderhead or something like that, when people on the ground were merely deciding whether they should take their umbrella. I’d think of these things, wandering to work…”

We walked to the house, and I tried to remember, No, he had never talked that way he had never said that kind of thing out loud, as long as I had known him.

“And now,” he said after supper, “well, very few people know of American Aviation. They either don’t know it, or they screw it up and say, ‘Oh, that’s the operation that’s going broke, or went broke.’ That’s good, because then I can give them my speech: ‘No, this isn’t going broke, this is American Aviation. We’ve got people who are pros…’ and all this sort of thing. And they are pros. This is one of the other things I wanted to do when I quit the wringer-washer job—I didn’t want to work with a bunch of… well I wanted to work with a more professional organization.”

We checked the Yankee for its ferry flight to Philadelphia, and I remembered what Jane Beaven had said the day before. “I don’t know him and I never will. But Bo was a changed man, when he went completely away from flying. It got to him, he was understimulated, he was bored. He doesn’t talk a great deal about what he feels, he doesn’t go on and on about anything. But when he quit at last, he had two choices of excellent jobs. One was with a big metals company and he would be there forever, and the other was with American Aviation which could, as far as we really knew, fold the next day. But after one interview I knew where we were going.” She had laughed out loud. “He kept saying, of course, ‘The metals company would be marvelous, and much more secure,’ and all that, and to me it was the biggest line of hogwash… I knew where we were going.”

The Yankee rolled out onto the runway, one of Beaven’s first flights after his years on the ground. “You’ve got it. Bo,” I said. “Your airplane.”

He pressed full throttle, tracked the centerline, and we found that the Yankee, over grass, on a hot day, is not a short-field airplane. We left the ground a good way down the runway, angling long and shallow up into the air.

The ten years absence showed, even in a man who at one time had been a better pilot than I could hope to be. He wasn’t thinking ahead of the airplane, he was rough on the controls, and the sensitive little Yankee pitched and rolled under his hands.

But oddly, he was perfectly confident. He was rough and he knew it, he was behind the plane and he knew it, but he also knew that all this was normal as he got used to flying again, and that he’d catch up before many minutes had gone by.

He flew the Yankee the way he last remembered to fly; he flew it like a North American F-100D. Our turn on course wasn’t a gentle sweeping general-aviation turn, it was WHAM! the wing slammed into a steep bank, dug into the air, turned , then flew back to wings-level in a furious hard whiplash.

I had to laugh. For the first time I could see what another human being saw, I could look inside his mind. And I saw not a little civilian Yankee slicing along at one hundred twenty-five miles per hour with a hundred horsepower spinning a fixed-pitch propeller up front, but a D-model F-100 single-seat day fighter streaking ahead of fifteen thousand pounds of thrust blasting diamond lights out the afterburner and the ground blurring by beneath us and that button-studded control stick under his hand, that magic grip that one need only touch to spin the world, or turn it upside-down or make the sky go black.

Читать дальше