For Tommy and Lori Spruce

And thinking of James T. Farrell

These are the slums of the heart.

JOHN D. MAC DONALD

DEAR CONSTANT READER,

This is a trunk novel, okay? I want you to know that while you’ve still got your sales slip and before you drip something like gravy or ice cream on it, and thus make it difficult or impossible to return. [1] In saying this, I assume you’re like me and rarely sit down to a meal — or even a lowly snack — without your current book near at hand.

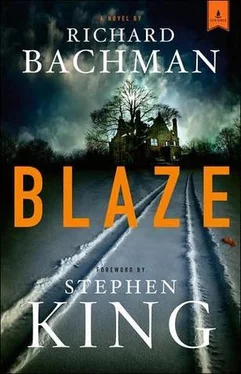

It’s a revised and updated trunk novel, but that doesn’t change the basic fact. The Bachman name is on it because it’s the last novel from 1966-1973, which was that gentleman’s period of greatest productivity.

During those years I was actually two men. It was Stephen King who wrote (and sold) horror stories to raunchy skin mags like Cavalier and Adam, [2] With this exception: Bachman, writing under the pseudonym of John Swithen, sold a single hard-crime story, “The Fifth Quarter.”

but it was Bachman who wrote a series of novels that didn’t sell to anybody. These included Rage, [3] Now out of print, and a good thing.

The Long Walk, Roadwork, and The Running Man . [4] The Bachman novel following these was Thinner, and it was no wonder I got outed, since that one was actually written by Stephen King — the bogus author photo on the back flap fooled no one.

All four were published as paperback originals.

Blaze was the last of those early novels—the fifth quarter, if you like. Or just another well-known writer’s trunk novel, if you insist. It was written in late 1972 and early 1973. I thought it was great while I was writing it, and crap when I read it over. My recollection is that I never showed it to a single publisher — not even Doubleday, where I had made a friend named William G. Thompson. Bill was the guy who would later discover John Grisham, and it was Bill who contracted for the book following Blaze, a twisted but fairly entertaining tale of prom-night in central Maine. [5] I believe I am the only writer in the history of English story-telling whose career was based on sanitary napkins; that part of my literary legacy seems secure.

I forgot about Blaze for a few years. Then, after the other early Bachmans had been published, I took it out and looked it over. After reading the first twenty pages or so, I decided my first judgment had been correct, and returned it to purdah. I thought the writing was okay, but the story reminded me of something Oscar Wilde once said. He claimed it was impossible to read “The Old Curiosity Shop” without weeping copious tears of laughter. [6] I have had the same reaction to Everyman, by Philip Roth, Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, and The Memory Keeper’s Daughter, by Kim Edwards — at some point while reading these books, I just start to laugh, wave my hands, and shout: “Bring on the cancer! Bring on the blindness! We haven’t had those yet!”

So Blaze was forgotten, but never really lost. It was only stuffed in some corner of the Fogler Library at the University of Maine with the rest of their Stephen King/Richard Bachman stuff.

Blaze ended up spending the next thirty years in the dark. [7] Not in an actual trunk, though; in a cardboard carton.

And then I published a slim paperback original called The Colorado Kid with an imprint called Hard Case Crime. This line of books, the brainchild of a very smart and very cool fellow named Charles Ardai, was dedicated to reviving old “noir” and hardboiled paperback crime novels, and publishing new ones. The Kid was decidedly softboiled, but Charles decided to publish it anyway, with one of those great old paperback covers. [8] A dame with trouble in her eyes. And ecstasy, presumably, in her pants.

The whole project was a blast — except for the slow royalty payments. [9] Also a throwback to the bad old paperback days, now that I think of it.

About a year later, I thought maybe I’d like to go the Hard Case route again, possibly with something that had a harder edge. My thoughts turned to Blaze for the first time in years, but trailing along behind came that damned Oscar Wilde quote about “The Old Curiosity Shop.” The Blaze I remembered wasn’t hardboiled noir, but a three-handkerchief weepie. Still, I decided it wouldn’t hurt to look. If, that was, the book could even be found. I remembered the carton, and I remembered the squarish type-face (my wife Tabitha’s old college typewriter, an impossible-to-kill Olivetti portable), but I had no idea what had become of the manuscript that was supposedly inside the carton. For all I knew, it was gone, baby, gone. [10] In my career I have managed to lose not one but two pretty good novels-in-progress. Under the Dome was only 50 pages long at the time it disappeared, but The Cannibals was over 200 pages at the time it went MIA. No copies of either. That was before computers, and I never used carbons for first drafts — it felt haughty, somehow.

It wasn’t. Marsha, one of my two valuable assistants, found it in the Fogler Library. She would not trust me with the original manuscript (I, uh, lose things), but she made a Xerox. I must have been using a next-door-to-dead typewriter ribbon when I composed Blaze, because the copy was barely legible, and the notes in the margins were little more than blurs. Still, I sat down with it and began to read, ready to suffer the pangs of embarrassment only one’s younger, smart-assier self can provide.

But I thought it was pretty good — certainly better than Roadwork, which I had, at the time, considered mainstream American fiction. It just wasn’t a noir novel. It was, rather, a stab at the sort of naturalism-with-crime that James M. Cain and Horace McCoy practiced in the thirties. [11] And, of course, it’s an homage to Of Mice and Men — kinda hard to miss that.

I thought the flashbacks were actually better than the front-story. They reminded me of James T. Farrell’s Young Lonigan trilogy and the forgotten (but tasty) Gas-House McGinty . Sure, it was the three Ps [12] Purple, pulsing, and panting.

in places, but it had been written by a young man (I was twenty-five) who was convinced he was WRITING FOR THE AGES.

I thought Blaze could be re-written and published without too much embarrassment, but it was probably wrong for Hard Case Crime. It was, in a sense, not a crime novel at all. I thought it could be a minor tragedy of the underclass, if the re-writing was ruthless. To that end, I adopted the flat, dry tones which the best noir fiction seems to have, even using a type-font called American Typewriter to remind myself of what I was up to. I worked fast, never looking ahead or back, wanting also to capture the headlong drive of those books (I’m thinking more of Jim Thompson and Richard Stark here than I am of Cain, McCoy, or Farrell). I thought I would do my revisions at the end, with a pencil, rather than editing in the computer, as is now fashionable. If the book was going to be a throwback, I wanted to play into that rather than shying away from it. I also determined to strip all the sentiment I could from the writing itself, wanted the finished book to be as stark as an empty house without even a rug on the floor. My mother would have said “I wanted its bare face hanging out.” Only the reader will be able to judge if I succeeded.

Читать дальше