Enjoyment is the sole reason many of us started to fly; we wanted to sample the stimulation of flight. Perhaps in the back of our minds, as we pushed the high-winged cabin into the sky, we thought, “This isn’t like I hoped it would be, but if it’s flying I guess it will have to do.”

A closed cabin keeps out rain and lets one smoke a cigarette in unruffled ease. This is a real advantage for IFR conditions and chain smokers. But is it flying?

Flying is the wind, the turbulence, the smell of exhaust, and the roar of an engine; it’s wet cloud on your cheek and sweat under your helmet.

I’ve never flown in an open-cockpit airplane. I’ve never heard the wind in the wires, or had only a safety belt between me and the ground. I’ve read, though, and know that’s how it once was.

Are we doomed by progress to be a colorless group who take a roomful of instruments from point A to point B by air? Must we get our thrill of flying by telling how we had the needles centered all the way down the ILS final? Must the joy of being off the ground come by hitting those checkpoints plus or minus fifteen seconds every time? Perhaps not. Of course, the ILSs and the checkpoints have an important place, but don’t the seat of the pants and the wind in the wires have their places too?

There are old-timers with frayed logbooks that stop at ten thousand hours. They can close their eyes and be back in the Jenny with the slipstream drumming on a fuselage fabric; the exhilaration of the wind rush through a hammerhead stall is there any time they call it up. They’ve experienced it.

It isn’t there for me. I started to fly in a Luscombe 8E in 1955, no open cockpits or wires for us new pilots. It was loud and enclosed, but it was above the traffic on the highways. I thought I was flying.

Then I saw Paul Mantz’s Nieuports. I touched the wood and the cloth and the wire that let my father look down on the men who fought in the mud of the earth. I never got that delicious excited feeling by touching a Cessna 140 or a Tri-Pacer or even an F-100.

The Air Force taught me how to fly modern airplanes in a modern efficient manner; no covering the airspeed indicator here. I’ve flown T-Birds and 86s and C-123s and F-100s. The wind hasn’t once gotten to my hair. It has to get through the canopy (“CAUTION—Do not open above 50 knots IAS”), then through the helmet (“Gentlemen, a square inch of this fiberglass can take an eighty-pound shock force”). An oxygen mask and a lowered visor complete my separation from possible contact with the wind.

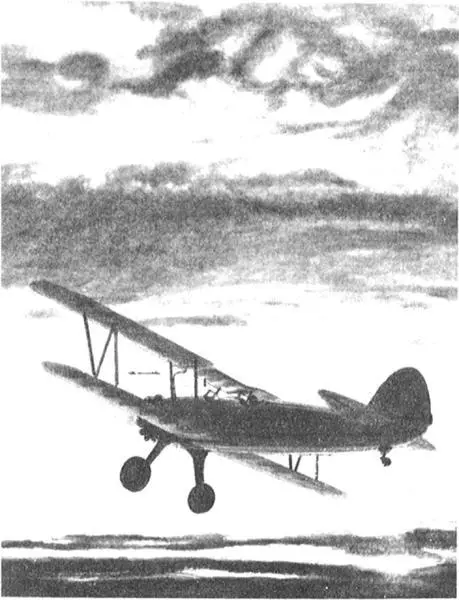

That’s the way it has to be now. You can’t fight MIGs with an SE-5. But the spirit of the SE-5 doesn’t have to disappear, does it? When I land my F-100 (chop the power when the main gear touches, lower the nose, pull the drag chute, apply brakes till you can feel the antiskid cycle), why can’t I go to a little grass strip and fly a Fokker D7 airframe with one hundred fifty modern horses in the nose? I’d pay a lot for the chance!

My F-100 will clip along at Mach One plus, but I don’t feel the speed. At forty thousand feet, the drab landscape creeps under the droptank as if I were in a strictly enforced twenty-five mile speed zone. The Fokker will do an indicated one hundred ten miles per hour, but it will do it at five hundred feet and in open air, for the fun of it. The landscape wouldn’t lose its color to altitude, and the trees and bushes would blur with speed. My airspeed indicator wouldn’t be a dial with a red-line somewhere over Mach One, it would be the sound of the wind itself, telling me to drop the nose a little and get ready to hop on the rudders, for this plane doesn’t land itself.

“Build a World War I airframe with a modern engine?” you ask. “You could get a four-place plane for the money!”

But I don’t want a four-place plane! I want to fly!

I shot down the Red Baron, and so what

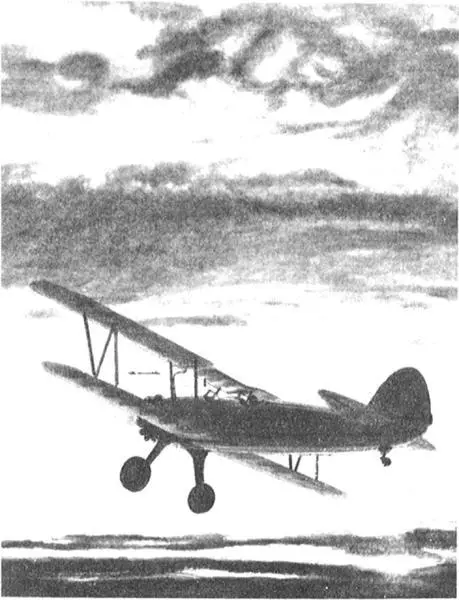

It was not a Mitty dream. It was no fantasy at all. That was a hard roaring black-iron engine bolted to the firewall ahead of my boots, those were real Maltese-crossed wings spanning out over my cockpit, that was the same ice-and-lightning sky I had known most of my life long, and over the side it was a long fall to the ground.

Now, down there in front of me, was a British SE-5 fighter plane, olive drab with blue-white-red roundels on the wings. He hadn’t seen me. It all felt exactly the way I had known it would feel, from reading the yellow old war-books of flight. Exactly that way.

I stepped hard on the rudder bar, pulled the joystick across the cockpit and rolled down on him, tilting the world about me in great sweeping tilts of emerald earth and white-flour cloud, and blasting slants of blue wind across my goggles.

While he flew along unaware, the poor devil.

I didn’t use the gunsight because I didn’t need it. I lined the British airplane between the cooling jackets of the two Spandau machine guns on the cowl in front of me, and pressed the firing button on the stick.

Little lemon-orange flames licked from the gun muzzles with a faint pop-pop over the storm of my dive. Yet the only move the SE made was to grow bigger between my guns.

I did not shout, “Die, Englander pig-dog!” the way the Hun pilots used to shout in the comic books.

I thought, nervously, You’d better hurry up and burn or it’ll be too late and we’ll have to do this all over again.

In that instant a burst of night swallowed the SE. It leaped up into an agonized snap roll, clouting black from its engine, pouring white fire and oil smoke behind it, emptying junk into the sky.

I dove past him like a shot, tasting the acid taste of his fires, twisting in my seat to watch him fall. But fall he did not. Smoke gushing dark oceans from his plane, he wobbled half-turn through a spin, pointed straight down at me, and opened fire with his Lewis gun. The orange light of the gun barrel flickered at my head, twinkling in dead silence from the middle of all that catastrophe. All I could think was, Nicely done. And that this must have been just the way it was.

The Fokker snatched into a vertical climb in the same instant that I hit the switch labeled SOOT ( foof! from beneath my engine) and the one next to it labeled SMOKE. The cockpit went dim in roiling yellow-black which I breathed in tiny gasps. Right rudder to push the airplane into a falling slide to the right, full back-stick to spin it. One turn… two… three… the world going round like a runaway Maytag. Then a choking recovery into a diving spiral, followed every foot by that river of wicked fog.

Presently the cockpit cleared and I recovered to level flight, a few hundred feet above the green farms of Ireland. Chris Cagle, flying the SE-5, turned a quarter mile away, rocking his wings in signal to join in formation and fly home.

As we crossed the trees side by side and touched our tailskids to the wide grass of Western Aerodrome, I counted that this had been an eventful day. Since dawn I had shot down one German and two British airplanes, had myself been shot down four times—twice in an SE-5, once in a Pfalz, once in this Fokker. It was a lively introduction to the way that a movie pilot earns his keep, and there was a month more of it to come.

The film was Roger Corman’s Von Richthofen and Brown , an epic featuring a fair amount of gore, some sex, a tampering with history, and twenty minutes of aerial footage that several living pilots nearly stopped living to produce. The gore and sex and history were make-believe, but the flying, as flying always is, was the real thing. Chris and I learned that first day in the air what every movie pilot since Wings has known: nobody has “ever told the airplanes that this is all in fun. The aircraft still stall and spin, they’ll have real mid-air collisions if you let them do it. No one else but pilots can understand this.

Читать дальше