Miss that Big Briefing In The Sky, and you have to find out for yourself about flying coast to coast in old airplanes. If you don’t get the word from someone else, an airplane has to teach you.

And the lesson? People can fly old open-cockpit biplanes thousands of miles, can learn things of their country, of the early pilots to whom aviation owes its life, and of themselves. Something perhaps, that no Briefing could ever teach.

I was supposed to write a story about the man, not to kill him in cold blood. But somehow I couldn’t make him believe that—it was one of those rare times that I had met a person so frightened he was alien, and I stood helpless to talk with him as though I spoke ancient Urdu. It was disconcerting, to find that words sometimes have no meaning, and no effect at all. The man who was to have been the central figure of the story advised me clearly that he was on to me, he knew that I was a puppet, a boor, an ingrate, and a mob of other unsavory characters all wrapped in a faded flying jacket.

A few years earlier, I might have experimented with violence to communicate with him, but this time I chose to leave the room. I walked out into the night air, and in the dim moonlight by the shore of the sea—for this was to have been a story of the man and his resort paradise.

The breakers boomed along the dark beach, flickering blue-green-phosphorous like gentle peaceful howitzers firing in the dark, and I watched the salt ocean rush in swift and steady, slow and back, hissing softly. I walked half an hour perhaps, trying to understand the man and his fear, and finally gave it up as a bad job. It was only then, turning away from the ground, that I happened to look up.

And there, over the elegant resort lands and over the sea, over the oblivious guests at the indoor bar and over me and all my little problems, was the sky.

I slowed, there on the sand, and at last stopped and looked way on up into the air. From past-horizon north to past-horizon south, from beyond land’s end to beyond the depths of the western sea, lived the billion-mile sky. It was very calm, very still.

Some high cirrus drifted along under a slice of moon, borne ever so carefully on a faint, faint wind. And I noticed something that night that I had never noticed before.

That the sky is always moving, but it’s never gone.

That no matter what, the sky is always with us.

And that the sky cannot be bothered. My problems, to the sky, did not exist, never had existed, never would exist.

The sky does not misunderstand.

The sky does not judge.

The sky, very simply, is.

It is, whether we wish to see that fact or to bury ourselves under a thousand miles of earth, or even deeper still, under the impenetrable roof of unthinking routine.

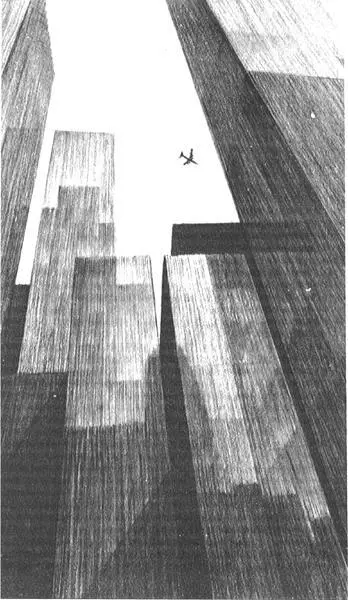

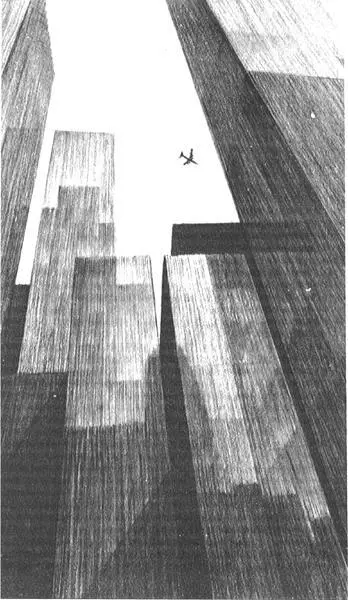

It happened a year later that for some reason I was in New York City, and everything was going wrong and my total assets equaled twenty-six cents and I was hungry and the very last place I wanted to be was in the prison streets of sundown Manhattan, with iron-barred windows and quintuple-lock doors. But it happened that I looked up, which is something one never does in Manhattan, of course, and again, as it had been by the sea—way on up there, way high over the canyons of Madison Avenue and Lexington and Park—was the sky. It was there. Unhurried. Unchanged. Warm and welcome as home.

What do you know, I thought. What do you know about that. No matter how tangled and twisted and distressful goes the life of an airplane pilot, he always has a home, waiting. For him always waits the joy of being back in the air, of looking down at and up to the clouds, for him always waits that inner cry, “I’m home again!”

“Bunch of mist, bunch of empty air,” the people of the ground will say. “Get your head out of the clouds, get your feet on the ground.” Yet in times as far separated as that lonely beach and the crowded Manhattan street, I was lifted from black despair into freedom. From annoyance and anger and fear to a thought, Hey! I don’t care! I’m happy!

Just by looking into the sky.

This kind of thing happens, perhaps, because pilots aren’t far-traveling wanderers after all. It may be that pilots are happy only when they are at home. And it may be that they are home only when they can somehow touch the sky.

Steel, aluminum, nuts and bolts

An airplane is a machine. It is not possible for it to be alive. Nor is it possible for it to wish or to hope or to hate or to love.

The machine that is called “airplane” is made of two sections, the “engine” and the “airframe,” each of which is built of common machine-building materials. There is no secret, no dark magic, there are no incantations said over any airplane in order to make it fly. It flies because of known and invariable laws which cannot be changed for any reason.

An “engine,” briefly, is a block of metal that has been drilled with certain holes and set with certain springs and valves and gears. It does not in any way come into life when it is bolted on the front of an airframe. Those vibrations through an engine are caused by the rapid burning of fuel within its cylinders, by the action of its moving parts, by the forces that a spinning propeller creates.

An “airframe” is a sort of cage built of steel tubing and sheet aluminum. It is tin and fabric and wire. It is nuts and bolts. An airframe is made to the calculations of the aircraft designer, who is a very wise and practical man who makes his living at this sort of thing and does not mess around with esoteric mumbo-jumbo.

There is no part in any airplane for which there does not exist a blueprint. There is no part which cannot be unscrewed into simple plates and castings and forgings. The airplane was invented. It did not “come into being,” it was never brought to life. An airplane is a machine as an automobile is a machine, as a chain saw is a machine, as a drill press is a machine.

Is there a voice in reply to this, from perhaps the newest of student pilots, saying that an airplane is a creature of the air, and so has special forces acting upon it that a drill press does not have?

Wrong. An airplane is not a creature. It is a machine: blind, dumb, cold, dead. Every force upon it is a known force. A million hours of research and flight tests have shown us all there is to know about an airplane: Lift-Weight-Thrust-Drag. Angles of attack, centers of pressure, power required versus power available, and parasite drag increases as the square of the airspeed.

Yet there are a few airplane pilots who somehow want to believe that this machine is an animal, that it is alive. Make certain that you do not believe it. That is absolutely impossible.

The takeoff performance of any aircraft, for instance, depends upon wing loading, power loading, airfoil coefficients, and upon density altitude, wind, slope and surface of the runway. All these are things that can be measured with tape measures and test machines, and when they are run through charts and computers, they give us an absolute minimum takeoff distance.

There is no sentence, no word, no hint in any technical manual ever printed that even remotely says that this machine’s performance can possibly change because of a pilot’s hopes or his dreams, or his kindness to his airplane. This is critically important for you to know.

I give you an example. I give you a pilot. Let’s say that his name is… oh… Everett Donnelly. Let’s say that he learned to fly in a 7AC Aeronca Champion. N2758E.

Then later, let’s say that Everett Donnelly became a first officer with United Air Lines, and then a captain, and that for fun he began looking for that same old Aeronca Champ. Let’s say he asked questions and wrote letters and searched for a year and a half across the country, and that at last he found what was left of N2758E, smashed under a fallen hangar at an abandoned airport. Let’s say he spent just under two years rebuilding the airplane, touching and finishing every nut and bolt and pulley and seam of it. And then perhaps he flew that Champ for five years, and perhaps he refused quite a few good offers from people who wanted to buy it, and perhaps he kept it in perfect condition because it was a part of his life that he enjoyed and because the airplane itself had become something that he loved.

Читать дальше