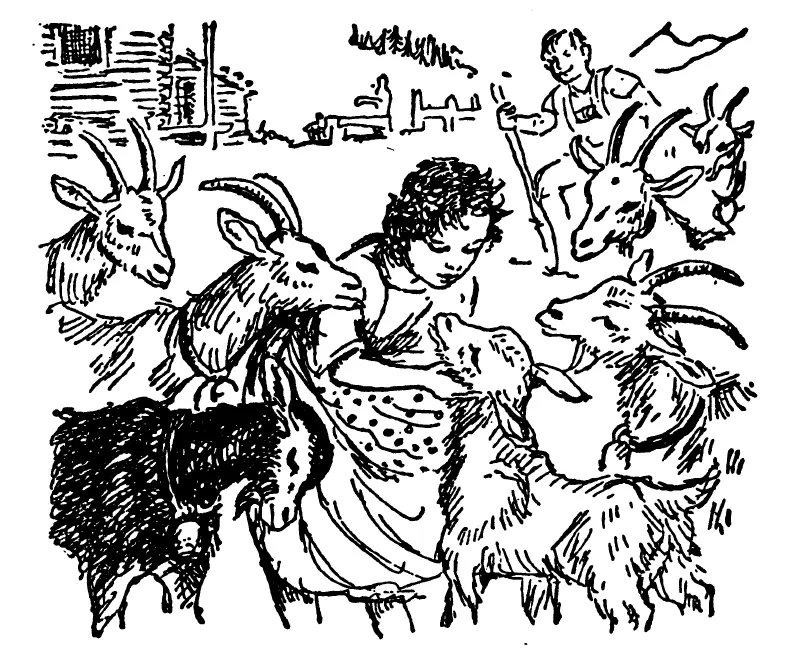

They pressed so close she was almost squashed between them but she did not mind that a bit. Only when the brown goat got too boisterous, she cried, ‘Really, Dusky, you’re as bad as Turk,’ and Dusky immediately drew back. Daisy stood a little aloof, looking as though she hoped no one could accuse her of behaving like Turk. She was always the more sedate of the two.

Peter was whistling as he came up the path, and soon the whole herd appeared, led by frisky Finch. They immediately bounded up to Heidi, pushing her from one side to the other as they greeted her in their own obstreperous fashion. She made her way through them to Snowflake who, being timid, had not been able to get near Heidi. Peter wanted to talk to Heidi himself, so he gave a particularly piercing whistle, which drove the animals off for the moment.

‘You might come up with me today,’ he said to her.

‘I can’t, Peter. My nice people from Frankfurt might come any minute now, and I must be here when they do.’

‘You keep saying that,’ he grumbled.

‘I shall go on saying it until they arrive,’ she answered. ‘I daresay you don’t think it’s necessary, but how could I not?’

‘Uncle would be here,’ he persisted.

At that moment, Uncle Alp called loudly from the hut, ‘What’s the delay? Is it the Field‐Marshal or his troops?’

At that Peter turned and slashed his stick through the air. The goats recognized the signal and ran off at full tilt to their high pasture and he followed them.

Heidi had brought several new ideas back with her from Frankfurt. She made her bed every morning now, tucking in the clothes so that it looked smooth and trim. Then she tidied up the hut, setting each chair in its proper place and putting anything which might be lying about back in the cupboard. After that she fetched a duster, climbed on a stool and polished the table till it shone. When her grandfather came in, he used to look round at her work, well pleased, and say to himself, ‘We look like Sunday every day now! Heidi didn’t go away for nothing.’

They had breakfast together as soon as Peter had gone that day, and then Heidi started the housework. But she did not get on with it very fast. First one thing, then another, distracted her. A sunbeam shone straight through the open window and seemed to be calling to her to come out. Out she ran, and found everything so beautiful and the ground so warm and dry that she could not resist sitting down for a while, just to look at the meadows and the trees and the mountains. Then she remembered she had left the three‐legged stool standing in the middle of the hut and that she had not polished the table, so up she jumped and ran in. But before long the rustling fir trees called her outside again. Grandfather was busy in the shed, but every now and then he came out to watch her dancing about in rhythm with the swaying branches. He had just gone in again when he heard her call, ‘Grandfather, Grandfather! Come quickly!’ He hurried out, afraid that something must be wrong, and saw her running away from him, down the slope.

‘They’re coming! They’re coming!’ she shouted over her shoulder. ‘That’s the doctor in front.’ She rushed on and greeted him affectionately. ‘Doctor, Doctor! Thank you again a thousand times!’

‘Bless you, child,’ cried the doctor. ‘What are you thanking me for?’

‘Why, for sending me home to Grandfather.’

The doctor’s face brightened. He had not expected a reception like this. Indeed he had felt rather gloomy as he climbed the mountain, and had not even noticed the beautiful surroundings. He had imagined that Heidi would scarcely remember him, for she had seen very little of him, and he was sure she would be disappointed to see him instead of her dear friends. But apparently she was overjoyed, for she held his arm tightly and lovingly.

‘Come, Heidi,’ he said, taking her hand in a fatherly way. ‘Take me to your grandfather and show me where you live.’

But she did not move. She was looking down the mountain path, puzzled. ‘Where are Clara and Grandmamma?’ she asked at last.

‘I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you, Heidi,’ he replied. ‘I’ve come alone. Clara has been very ill and wasn’t fit to travel, and so of course Grandmamma stayed with her. But they’ll come in the spring, as soon as the days begin to get longer and warmer.’

Heidi was very upset then, and found it difficult to believe that what she had looked forward to so long was not going to happen after all. For a minute or two she could not speak, and the doctor gazed in silence about him. Then the pleasure she had felt as she ran to meet him came back to her, and she remembered that he, at least, had come to visit her.

She looked up at him and saw the lonely look in his eyes which she did not remember seeing there when she was in Frankfurt. She could not bear to see anyone unhappy, least of all the good doctor, and thinking his sadness must be because Clara and her grandmother had not been able to accompany him, she tried to comfort him.

‘Oh, it will soon be spring,’ she reminded him, and herself. ‘Time goes quickly up here. They’ll be able to stay longer then, and Clara will like that. Now come and see Grandfather.’

They went towards the hut hand in hand. In her anxiety to chase the shadow from his eyes, she told him again and again how soon summer would come, and almost convinced herself of it, so that when they reached her grandfather, she called out, ‘They haven’t come yet, but they will quite soon.’

The doctor seemed no stranger to Uncle Alp, for Heidi had talked a great deal about him, and the old man put out his hand and welcomed him warmly. They sat down together on the seat outside, and the doctor made room for Heidi beside him. Sitting there in the September sunshine, he told them how Mr Sesemann had suggested he should come, and that it had seemed to him a good idea because he hadn’t been feeling well lately. Then he whispered to Heidi that there was something being brought up the mountain for her, something from Frankfurt, which would give her much more pleasure than he could. This news, of course, excited all her curiosity.

‘I hope you’ll spend as many of these beautiful autumn days as you can on the mountain,’ said Uncle Alp, explaining that unfortunately they could offer him no lodging in the hut, but that there was a good little inn at Dörfli. ‘There is no need to go all the way back to Ragaz,’ he assured him. ‘Ours is a simple little place, but clean. Then you could come up to us every day, which I know will do you good, and if you would like it, I will be your guide over any part of the mountains you wish to see.’

This suited the doctor very well and he accepted the suggestion with pleasure.

The sun by now was overhead, for it was midday, and the fir trees stood motionless. Uncle Alp went indoors and brought out the table which he placed in front of the seat. ‘Heidi,’ he said, ‘bring out what we need. The doctor must take us as he finds us. Our food is simple, but he will agree that the dining‐room is fine!’

‘I do indeed,’ said the doctor, looking down on the valley, which was gleaming in the sunlight. ‘I shall be glad to accept your invitation. Everything will taste extra good up here.’

Heidi ran back and forth, bringing out everything she could find in the cupboard. She felt very proud to be helping to entertain the doctor. Grandfather was preparing the food, and came out presently with a steaming jug of milk and a piece of golden toasted cheese. Then he cut thin slices of the delicious meat which he had dried in the open air during the summer, and the doctor enjoyed his meal more than any he had eaten that year.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу