1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...50 He stood up and held out his hand. ‘I shall count on seeing you back among us next winter, old friend,’ he said. ‘I should be sorry if we had to put any pressure upon you. Give me your hand and promise you’ll come down and live among us again and be reconciled to God and to your neighbours.’

Uncle Alp shook hands with him, but said slowly, ‘I know you mean well, but I can’t do what you ask. That’s final. I shan’t send the child to school, nor come back to the village to live.’

‘May God help you, then,’ said the pastor and he went sadly out of the hut and down the mountain.

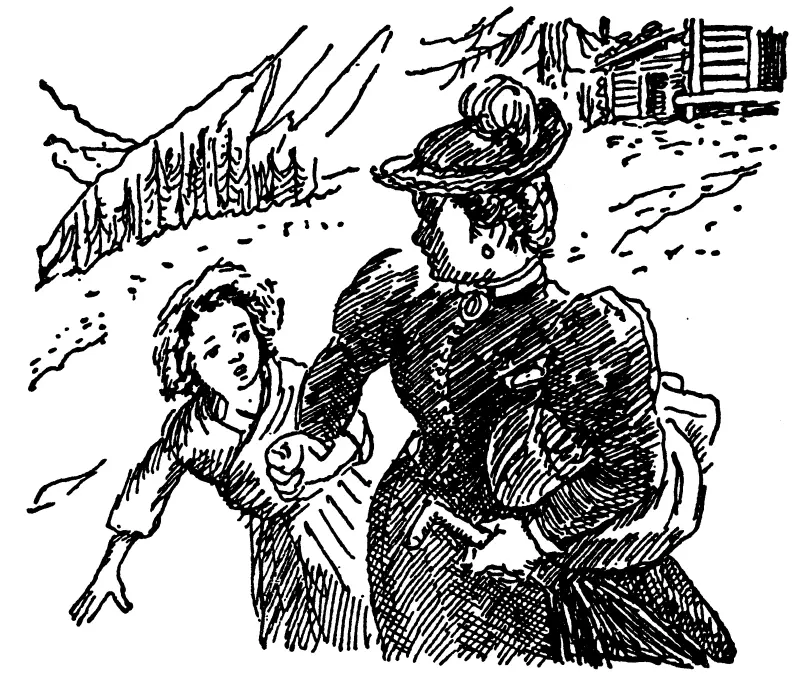

He left Uncle Alp out of humour. After dinner when Heidi said as usual, ‘Now it’s time to go to Grannie’s,’ he only replied, ‘Not today,’ and didn’t say another word that day. Next morning she asked again if they were going to Grannie’s, and he only said gruffly, ‘We’ll see.’ But before the dinner dishes had been cleared away they had another visitor. This time it was Detie. She was wearing a smart hat with a feather and a long dress which swept the ground as she walked — and the floor of the hut was not particularly good for it. Uncle Alp looked her up and down in silence. However Detie was all amiability, and started to talk at once.

‘How well Heidi looks,’ she exclaimed. ‘I hardly recognize her! You’ve certainly looked after her all right. Of course I always intended to come back for her because I know she must be in your way, but two years ago I just didn’t know what else to do with her. I’ve been on the lookout for a good home for her ever since, and that’s why I’m here now. I’ve heard of a wonderful chance for her. I’ve been into it all thoroughly and everything’s all right. It’s a chance in a million! The family I work for have got some very rich relations who live in one of the best houses in Frankfurt. They’ve a little girl who’s paralysed on one side and very delicate. She has to be in a wheel‐chair all the time and has lessons by herself with a tutor. That’s terribly dull for her and she longs for a little playmate. They’ve been talking about it at my place because of course my family, being relations, are very sorry for her and would like to help her. That’s how I heard what they wanted — a simple, unspoilt child to come and stay with her, they said, someone a bit out of the ordinary. I thought of Heidi at once, and I went and saw the lady who keeps house for them. I told her all about Heidi and she said she thought she would do. Isn’t that wonderful? Isn’t Heidi a lucky girl? And, if they like her, and anything were to happen to their daughter, which is quite likely, you know, it might well be that…’

‘Have you nearly finished?’ Uncle Alp interrupted her, having listened so far in silence.

Detie tossed her head in exasperation. ‘Anyone would think I’d been telling you something quite unimportant,’ she said. ‘There’s no one else in the whole district who wouldn’t be thankful to hear such a piece of news.’

‘Tell them then,’ he said drily, ‘it doesn’t interest me.’

Detie flew up like a rocket at these words. ‘If that’s what you think, let me tell you something more. The child will soon be eight and she doesn’t know a thing and you won’t let her learn. Oh yes, they told me in Dörfli about your not sending her to school or to church. But she’s my sister’s child and I’m still responsible for her welfare. And when the chance of such good fortune has come her way, only a person who doesn’t care what happens to anyone could want to keep her from it. But I shan’t let you, I warn you, and everyone in Dörfli’s on my side. Also I’d advise you to think twice before taking the matter to court. You might find things being remembered which you’d rather forget. There’s no knowing what may come to light in a court of law.’

‘That’s enough,’ thundered the old man, with his eyes ablaze. ‘Take her then and spoil her. But don’t ever bring her back to me. I don’t want to see her with a feather in her hat or hear her talk as you have done today.’ And he strode out of the hut.

‘You’ve made Grandfather angry,’ said Heidi, giving her aunt a far‐from‐friendly look.

‘He’ll get over it,’ said Detie. ‘Come on now, where are your clothes?’

‘I’m not coming,’ said Heidi.

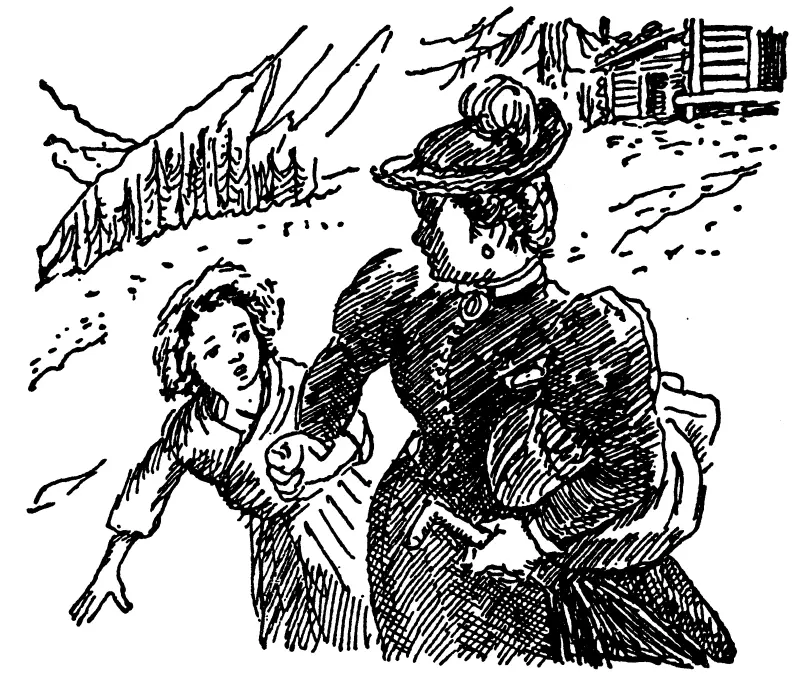

‘Don’t talk nonsense,’ snapped her aunt, but continued in a coaxing tone, ‘you don’t know what a good time you’re going to have.’ She went to the cupboard and took out Heidi’s things and made them into a bundle. ‘Put your hat on. It’s pretty shabby, but it’ll have to do. Hurry now, we must be off.’

‘I’m not coming,’ Heidi repeated.

‘Don’t be stupid and obstinate like one of those old goats!’ snapped Detie again. ‘I suppose it’s from them you’ve learned such behaviour. Just you try to understand now. You saw how angry your grandfather was. You heard him say he didn’t want to see us again. He wants you to go with me, so you’d better obey if you don’t want to make him angrier still. Besides you can’t think how nice it is in Frankfurt and how much there is going on there. And if you don’t like it you can always come back here. Grandfather will be in a better mood by then.’

‘Could I come straight back again this evening?’ asked Heidi.

‘Well, no. We shall only get as far as Mayenfeld today. Tomorrow we’ll go on by train, but you can always get back the same way if you want to come home. It doesn’t take long.’ Detie caught hold of Heidi with one hand, and tucked the bundle of clothes under the other arm, and so they set off down the mountain.

It was still too early in the year for Peter to be taking the goats up to the pasture, so he was at school in Dörfli — or should have been. But every now and then he played truant, for he thought school a great waste of time and could see no point in trying to learn to read. He liked much better to wander off and gather wood, which was always needed. On this particular day he was just coming home with an enormous bundle of hazel twigs when he saw Heidi and Detie. ‘Where are you going?’ he asked, as they came up to him.

‘I’m going to Frankfurt on a visit with Auntie,’ said Heidi, ‘but I’ll come in and see Grannie first. She’ll be expecting me.’

‘No, you won’t, there’s no time for that,’ said Detie firmly, as Heidi tried to pull her hand away. ‘You can go and see her when you come back.’ And she kept tight hold of her and hurried on. She was afraid Heidi would change her mind again, if she went in there, and the old woman would certainly take her side. Peter rushed into the cottage and flung his sticks on the table as hard as he could. He just had to relieve his feelings somehow. Grannie jumped up in alarm and cried, ‘Whatever’s that noise?’ His mother, who had almost been knocked out of her chair, said in her usual patient voice, ‘What’s the matter, Peterkin? Why are you so wild?’

‘She’s taking Heidi away,’ he shouted.

‘Who is? Where are they going?’ asked Grannie anxiously, though she could guess the answer, for her daughter had seen Detie pass on her way up to Uncle Alp’s, and had told her about it then. Now she opened the window and called beseechingly, ‘Don’t take the child away from us, Detie!’ But they had hurried on, and though they heard her voice, they couldn’t make out the words, but Detie guessed what they were and pulled Heidi along as fast as she could go.

‘That was Grannie calling. I want to go and see her,’ said Heidi, trying again to free her hand.

‘We can’t stop for that, we’re late as it is,’ retorted Detie. ‘We don’t want to miss the train. Just you think of the wonderful time you’ll have in Frankfurt, and when you come back again — if indeed you ever want to, once you’re there — you can bring a present for Grannie.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу