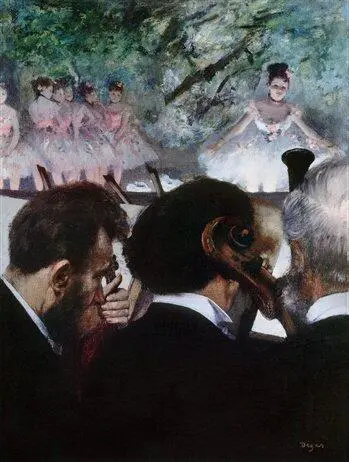

Oil on wood, 19.7 × 27 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

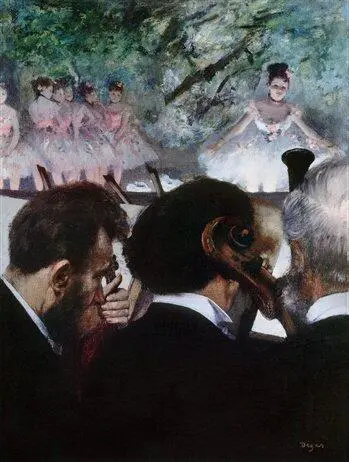

Orchestra Musicians, 1872.

Oil on canvas, 69 × 49 cm.

Städel-Museum, Frankfurt.

Around the time the notorious 1863 Salon des Refusés signalled the clear distinction in French painting between a revolutionary avant-garde and the conservative establishment, Edgar Degas painted a self-portrait which could hardly have looked less like that of a potential revolutionary. He appears a perfect middle-class gentleman or, as the Cubist painter André Lhote put it, like ‘a disastrously incorruptible accountant’. Wearing the funereal uniform of the 19 th-century male bourgeois which, in the words of Baudelaire, made them look like ‘an immense cortège of undertakers’ mutes’, Degas politely doffs his top hat and guardedly returns the scrutiny of the viewer. A photograph taken a few years earlier, preserved in the French National Library, shows him looking very much the same, although his posture is more tense and awkward than in the painting.

The Degas in the photo holds his top hat over his genital area in a gesture unconsciously reminiscent of that of the male peasant in Jean-François Millet’s Angelus . Salvador Dalí’s provocative explanation of the peasant’s uncomfortable stance was that he was attempting to hide a burgeoning erection. Degas’ sheepish and self-conscious expression also suggests an element of sexual modesty. For an artist who once said that he wanted to be both ‘illustrious and unknown’, any speculation about his sexuality would have seemed to him an unpardonable and irrelevant impertinence.

Nevertheless, the peculiar nature of much of Degas’ subject matter, the stance of unrelenting misogyny he adopted, and the very lack of concrete clues about his personal relationships have fuelled such speculation from the beginning. As early as 1869 Manet confided to the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, with whom Degas was conducting a bizarre and somewhat unconvincing flirtation, ‘He isn’t capable of loving a woman, much less of telling her that he does or of doing anything about it.’ In the same year, Morisot wryly described in a letter to her sister how Degas ‘came and sat beside me, pretending to court me – but this courting was confined to a long commentary on Solomon’s proverb, ‘Woman is the desolation of the righteous’…’.

Rumours of a sexual or emotional involvement with another gifted female painter, the American Mary Cassatt, can also be fairly discounted with confidence, although the fact that Cassatt burnt Degas’ letters to her might suggest that there was something that she wished to hide. Degas’ failure to form a serious relationship with any member of the opposite sex has been attributed to a variety of causes, such as the death of his mother when he was at the sensitive age of thirteen, an early rejection in love, and impotence resulting from a venereal infection. This last theory is based on a jocular conversation between Degas and a model towards the end of his life and need not be taken too seriously.

In 1858, Degas formed an intense and sentimental friendship with the painter Gustave Moreau. The emotional tone of Degas’ letters to the older artist might suggest to modern eyes an element of homosexuality in their relationship. ‘I am really sending this to you to help me wait for your return more patiently, whilst hoping for a letter from you… I do hope you will not put off your return. You promised that you would spend no more than two months in Venice and Milan.’

But whereas Moreau’s paintings exude an air of latent or even overt homosexuality, the same cannot be said of Degas’. There are accounts of Degas chatting in mellow and contented moods with models and dancers towards the end of his life, but it seems likely that, in common with many 19 th-century middle-class men, he was afraid of and found it hard to relate to women of his own class. His more outrageously misogynistic pronouncements convey a strong sense of his fear.

‘What frightens me more than anything else in the world is taking tea in a fashionable tea-room. You might well imagine you were in a hen-house. Why must women take all that trouble to look so ugly and be so vulgar?’ or ‘Oh! Women can never forgive me. They hate me. They can feel that I leave them defenceless. I show them without their coquetry, as no more than brute animals cleaning themselves!… They see me as their enemy – fortunately, for if they did like me, that would be the end of me!’

Degas’ portraits of middle-class women have faces, unlike his dancers, prostitutes, laundresses, milliners, and bathers who are usually stereotyped or quite literally faceless. On the other hand, these middle-class women may seem intelligent, rational, and sensitive, but are nevertheless a grim lot, without warmth or sensuality. Many of Degas’ female relatives seem to be overwhelmed by frigid and loveless melancholy. His nieces Giovanna and Giulia Bellelli turn from one another without the slightest trace of sisterly intimacy or affection. Grimmest of all is the portrait of his aunt, the Duchess of Montejasi Cicerale, and her two daughters in which the implacable old woman seems to be separated from her offspring by an unbridgeable physical and psychological gulf.

The theme of tension and hostility between the sexes underlies many of Degas’ most ambitious works of the 1860s, both in genre-like depictions of modern life such as Pouting and Interior (formerly known as The Rape and probably inspired by Émile Zola’s novel Thérèse Raquin ) and in elaborate historical scenes such as Young Spartans Exercising and Scene of War in the Middle Ages . This last – the most lurid and sensational picture Degas ever painted – shows horsemen shooting arrows at a group of nude women. The women’s bodies show no wounds or blood, but fall in poses suggestive more of erotic frenzy than of the agony of death. From the time that Degas reached maturity as an artist in the 1870s, most of his depictions of women – apart from a few middle-class portraits – include more than a suggestion that the women are prostitutes. Prostitution in 19 th-century Paris took a wide variety of forms, from the bedraggled street-walker desperate for a meal to the ‘Grande Horizontale’ able to charge a fortune for her favours. Virtually any woman who had to go out to work and earn a living was regarded as also liable to sell her body. So it was that Degas’ depictions of singers, dancers, circus performers, and even milliners and laundresses could have disreputable connotations for his contemporaries that might not always be apparent today.

A Woman Ironing, 1873.

Oil on canvas, 54.3 × 39.4 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

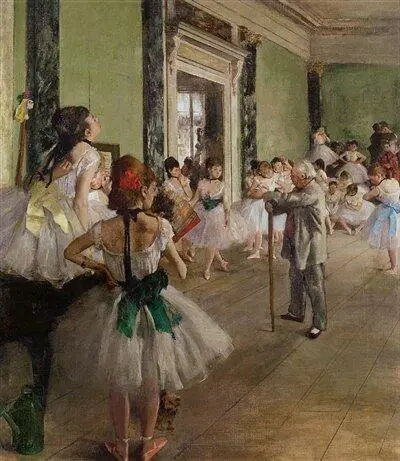

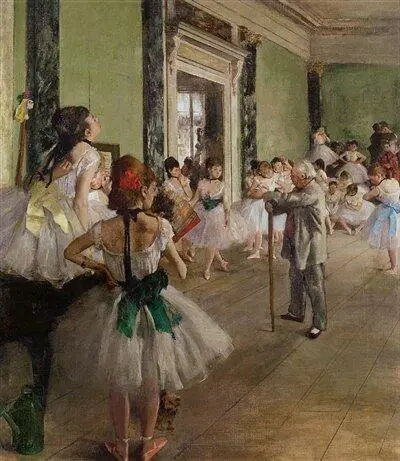

The Dance Class, c. 1873–1876.

Oil on canvas, 85.5 × 75 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

It was during the Second Empire (from 1852 to 1871) that Paris consolidated its reputation as the pleasure capital of Europe. That ‘love for sale’ was one of the chief attractions of Paris for foreign visitors is made abundantly clear by the operetta La Vie Parisienne composed by Jacques Offenbach for the 1867 Paris World Exhibition. The libretto, written by Degas’ close friend Ludovic Halévy and his collaborator Henri Meilhac, shamelessly celebrates Paris’ reputation as ‘the modern Babylon’ and a great focus for venal love.

Читать дальше