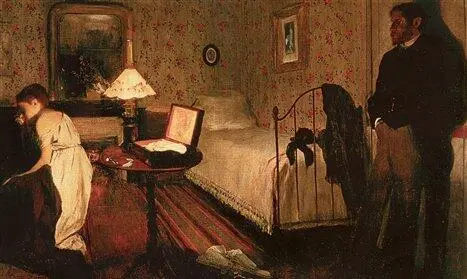

Oil on canvas, 56.5 × 46 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

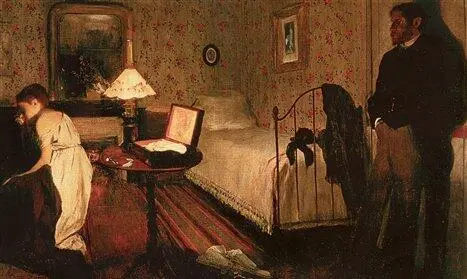

Interior (The Rape) (detail), c. 1868–1869.

Oil on canvas, 81.3 × 116.3 cm.

The Philadelphia Museum of Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

The Ballet from “Robert le Diable”, 1871.

Oil on canvas, 66 × 54.3 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The second difference between Degas and the Impressionists was in his attitude towards drawing. Renoir and his friends had been accused of not knowing how to draw because, in their work, the vibrations of air and light had the effect of blurring their line; their colour predominated over their drawing. For Degas drawing always came first.

After the death of Degas’ father in 1873, the Degas family bank failed and there was nothing left for the painter but to rely on his art. Like the other Impressionists, he suffered from the fact that his paintings were impossible to sell and, like Renoir, Monet, Sisley, and Camille Pissarro, he went to Durand-Ruel to ask for money. And, like Sisley, he never painted commissions, he worked only on what interested him. He kept repeating, reworking, and varying his same favourite motifs, he liked improving himself. His friends recounted how he could start over and over again on one and the same work without ever fully completing it.

At the close of the 1870s, Degas added cabaret scenes to his repertoire – before Manet painted his Bar at the Folies-Bergère . What is represented in The Absinthe Drinker is, in fact, the work of a stage or film director. In 1877, Degas painted two paintings, Women on a Café Terrace , sometimes called Café, Boulevard Montmartre and Café-Concert at ‘ The Ambassadors ’. In these, the painter seems to be representing a moment glimpsed at random. Objectively and instantaneously the painter sets down on canvas the posturing, gestures, and expressions of the ladies as they chatter among themselves. “M. Degas seems to have hurled a challenge at the Phillistines, that is to say the classicists,” wrote the critic Alexandre Pothey in an article on the third exhibition of the Impressionists. “The women in Women on a Café Terrace are frighteningly realistic. These painted, withered creatures, reeking of vice, cynically recounting the events and gestures of the day – you’ve seen them, you know them, and you’ll come across them again on the boulevards soon” (L. Venturi, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 303).

It seems strange that as refined an artist as Degas, a frequenter of society salons, would have been aware in Paris of those washerwomen and pressers who became the objects of his study. Yet, when he was in New Orleans and felt nostalgic for France, it was the washerwomen who embodied and symbolised the French life of his time for him, to which he dreamt of returning as quickly as possible. He drew women leaning over their irons and found an original grace and beauty in their repetitive movements. His firm line set down the mechanics of their movements, while the colour, by means of a few light patches, gave the appearance of a black and white photograph as it is being developed ( Two Laundresses ).

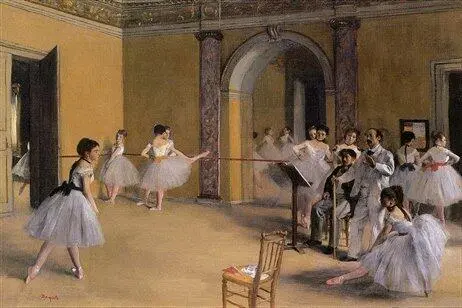

He painted ballet classes during lessons and as the dancers rested. It was rare for a ballet dancer to appear on his canvases as an airy, ethereal vision. Drawing, in these instances, makes way for colour to play the principal role. In the unreal atmosphere of the stage, the pink, sky-blue, and white tutus glitter and disappear. Most often, the ballet dancer in a Degas work is shown simply as a woman exhausted from pushing herself too hard. She has lost her stage charm. She exercises endlessly at the bar, and she strains as she stretches her tired legs. She is weak and miserable. The truth of everyday life would enter in at the moments when the ballet dancer was protected from the gaze of strangers, or when, bent over with fatigue, she would have to go through the humiliation of a long wait to be seen by the theatrical director ( Waiting , New York, Havemeyer Collection).

At the sixth Impressionist exhibition everyone marvelled at the wax statuette of a ballet dancer, almost one metre high, The Little Ballet Dancer . The tutu was of real white tulle, the bodice of waxed yellow canvas, the hair was knotted in a ponytail with a red satin ribbon, and the ballet slippers had yellow laces. Upright, in ballet position, her hands are behind her back, her head thrown back. “With her tarlatan petticoat, skinny, and as ugly as can be,” wrote the critic Charles Ephrussi, “but standing erect, arching back, and swaying, with that angular movement common to dance apprentices. She is rendered firmly, boldly, and with shrewdness, in a way that conveys, with infinite wisdom, the private demeanor and manner as well as the profession, embodied in the person… An ordinary artist would have turned this dancer into a puppet. M. Degas has turned her into a distinct, incisive, technically precise work, and in a truly original form” ( Degas Inédit [Degas Unpublished ], op. cit., p. 336–337).

The nude was no less important as an object of study for Degas: he drew it tirelessly all his life. “The same subject has to be done ten, a hundred times. Nothing in art should look like an accident, even movement” (J. Bouret, op. cit., p. 58). Movement, still more movement, always movement… Professional models would pose for Degas; his demands seemed absurd to them. Instead of sitting the young woman down or placing her, standing, in a well defined pose, he asked her to dry herself and do up her hair. Was the painter even drawing her? No: he stood standing against the wall, arms folded across his chest, watching her. Occasionally he climbed on a stool and watched her from above. Only after the model left would he begin to draw. Degas gained access to a world that, until then, had never let people from the outside come near: he represented women in their private surroundings, which belonged to them alone. He drew them in poses in which it is impossible to pose. She washes, squatting, in the bathtub. She combs her long hair, which a moment later she will toss back. Twisting around clumsily, she dries her back. Each drawing and each pastel seems to represent one image from an endless film of women washing and grooming themselves.

As he grew older, Degas made more and more sculpture. “With my eyesight going,” he said to the dealer Vollard, “I now have to take up blind men’s work” (J. Bouret, op. cit., p. 209). He modelled, in wax, what he knew best: ballet dancers, horses, and nudes. Ambroise Vollard was crestfallen to see how Degas would destroy his wax masterpieces so he could have the pleasure, as he put it, of starting them again. In his last years, Degas was almost completely blind. He died 27 September 1917. Among the group of several friends who came to accompany him to Montmartre cemetery there was only one Impressionist: Claude Monet. The other friend who had survived him, Renoir, was confined to an invalid’s armchair. In the midst of the First World War, the painter’s death went almost unnoticed.

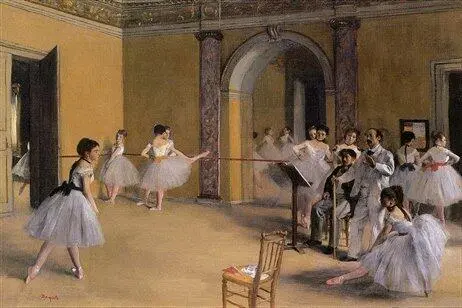

The Dance Foyer at the Opera on the rue Le Petelier, 1872.

Oil on canvas, 32.7 × 46.3 cm.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The Dancing Class (detail), c. 1870.

Читать дальше