4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the United States by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers , in 2016

Copyright © Michael Chabon 2016

Cover design by Anna Morrison

Michael Chabon asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. Scout’s honor.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007548910

Ebook Edition © October 2016 ISBN: 9780008189860

Version: 2018-06-11

To them, seriously

To them

There is no dark side of the moon, really. Matter of fact, it’s all dark.

—Wernher von Braun

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication 1

Dedication 2

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Michael Chabon

About the Publisher

In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it. Wherever liberties have been taken with names, dates, places, events, and conversations, or with the identities, motivations, and interrelationships of family members and historical personages, the reader is assured that they have been taken with due abandon.

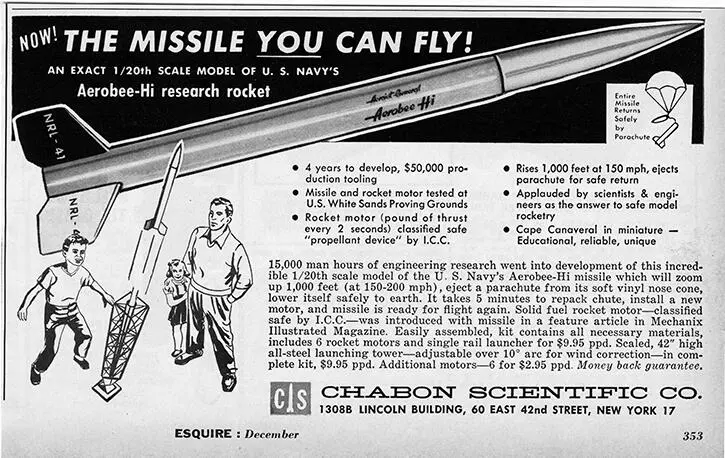

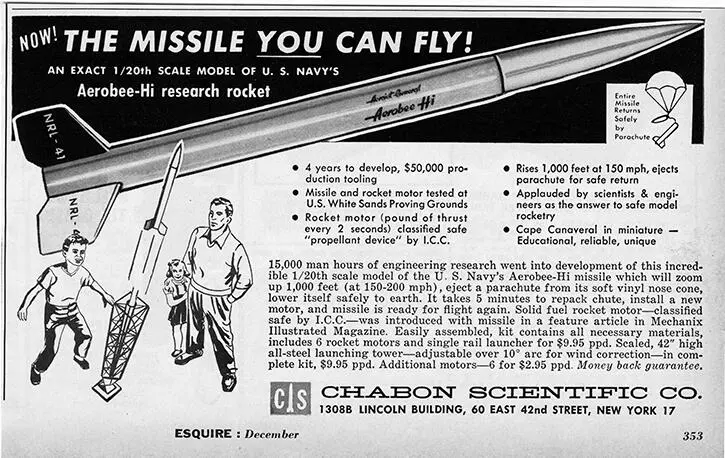

Advertisement , Esquire, October 1958

This is how I heard the story. When Alger Hiss got out of prison, he had a hard time finding a job. He was a graduate of Harvard Law School, had clerked for Oliver Wendell Holmes and helped charter the United Nations, yet he was also a convicted perjurer and notorious as a tool of international communism. He had published a memoir, but it was dull stuff and no one wanted to read it. His wife had left him. He was broke and hopeless. In the end one of his remaining friends took pity on the bastard and pulled a string. Hiss was hired by a New York firm that manufactured and sold a kind of fancy barrette made from loops of piano wire. Feathercombs, Inc., had gotten off to a good start but had come under attack from a bigger competitor that copied its designs, infringed on its trademarks, and undercut its pricing. Sales had dwindled. Payroll was tight. In order to make room for Hiss, somebody had to be let go.

In an account of my grandfather’s arrest, in the Daily News for May 25, 1957, he is described by an unnamed coworker as “the quiet type.” To his fellow salesmen at Feathercombs, he was a homburg on the coat rack in the corner. He was the hardest-working but least effective member of the Feathercombs sales force. On his lunch breaks he holed up with a sandwich and the latest issue of Sky and Telescope or Aviation Week . It was known that he drove a Crosley, had a foreign-born wife and a teenage daughter and lived with them somewhere in deepest Bergen County. Before the day of his arrest, my grandfather had distinguished himself to his coworkers only twice. During Game 5 of the 1956 World Series, when the office radio failed, my grandfather had repaired it with a vacuum tube prized from the interior of the telephone switchboard. And a Feathercombs copywriter reported once bumping into my grandfather at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn, where the foreign wife was, of all things, starring as Serafina in The Rose Tattoo . Beyond this nobody knew much about my grandfather, and that seemed to be the way he preferred it. People had long since given up trying to engage him in conversation. He had been known to smile but not to laugh. If he held political opinions—if he held opinions of any kind—they remained a mystery around the offices of Feathercombs, Inc. It was felt he could be fired without damage to morale.

Shortly after nine o’clock on the morning of the twenty-fourth, the president of Feathercombs heard a disturbance outside his office, where a quick-witted girl had been positioned to filter out creditors and tax inspectors. A male voice spoke with urgency that scaled rapidly to anger. The intercom on the president’s desk buzzed and buzzed again. He heard a chime of glass breaking. It sounded like a telephone when you slammed down the receiver. Before the president could rise from his chair to see what the matter was, my grandfather muscled into the room. He brandished a black handset (in those days a blunt instrument) that trailed three feet of frayed cord.

Back in the late 1930s, when he wasn’t hustling pool, my grandfather had put himself through four years at Drexel Tech by delivering pianos for Wanamaker’s department store. His shoulders spanned the doorway. His kinky hair, escaped from its daily paste-down of Brylcreem, wobbled atop his head. His face was so flushed with blood that he looked sunburned. “I never saw anyone so angry,” an eyewitness told the News . “You could almost smell smoke coming off him.”

For his part, the president of Feathercombs was astonished to discover that he had approved the firing of a maniac. “What’s this about?” he said.

It was a pointless question, and my grandfather disdained to answer it; he was opposed to stating the obvious. Most of the questions people asked you, he felt, were there to fill up dead space, curtail your movements, divert your energy and attention. Anyway, my grandfather and his emotions were never really on speaking terms. He took hold of the frayed end of the telephone cord. He wound it twice around his left hand.

The president tried to stand up, but his legs got tangled in the kneehole of his desk. His chair shot out from under him and toppled over, casters rattling. He screamed. It was a fruity sound, halfway to a yodel. As my grandfather fell on top of him, the president twisted himself toward the window overlooking East Fifty-seventh Street. He just had time to notice that passersby seemed to be crowding together on the sidewalk below.

Читать дальше