I was grateful that a UK trip had come up; I knew it would be a helpful distraction from the pain. The sleepless flight wasn’t helping, though, as memories of the wedding played on my mind all night. Jammed into my coach-class seat, staring out the window into the darkness, I felt my heart free-falling into nothing, as lonely and endless as the cold midnight sky.

A lifetime of secret sadness was washing over me. This certainly wasn’t my first heartbreak. I felt stuck in a recurring cycle of unexpressed feelings, repeatedly watching the women I’d fallen for walk away with someone else. It wasn’t that they’d rejected me—they’d never even known how I felt because I couldn’t tell them. I couldn’t tell anyone.

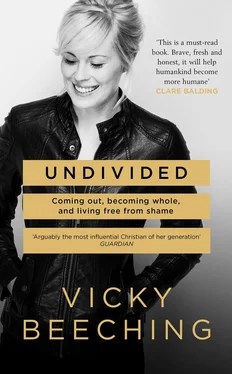

Since childhood, the church had taught me that homosexuality was an “abominable sin.” As a result, I couldn’t accept my own gay orientation. As an adult, my only survival solution was to shelve my feelings, keep them entirely private, and assume I’d never be able to date or marry. This way I could still belong to my faith community, keep my livelihood—the church-music career I loved—and not risk losing everything and everyone.

I was only twelve or thirteen when I first realized I was different, and knowing how “sinful” these feelings were caused waves of shame to crash over me. At that age, I’d felt shame before—when I’d lied to my parents about something small or failed to do school homework. But the feelings around my sexuality were different. This wasn’t shame about anything I’d done ; it was shame about who I was .

I’d first fallen in love around my fourteenth birthday, and, in the way of teenagers, I fell hard. Everything she said was magical. Everything she did captivated me. Our class had been together for a couple of years already, but as with most kids, puberty brings a totally new perspective on people you’ve been next to every day and never noticed.

Suddenly, I realized how incredibly blue her eyes were, how gracefully her body moved, and I could pick out the sound of her voice from another room. I wanted to be around her, to matter to her, to hear her thoughts on everything and anything. It was unlike anything I’d ever felt before and definitely a world away from the platonic emotions I had for boys.

One fateful day she confided in me that she’d met an amazing guy and that they were dating. The moment I heard this, it felt like all the lights in my world went out. I went home that night and sobbed into my carpet, utterly heartbroken and weighed down by the shame of my “sinful attractions.” After hours of crying, my thoughts kept turning to suicide. I told God I’d rather end my own life now if I had to continue to live with the tension of being gay and Christian; it was just too much to bear. If this was just the first of many such broken hearts, I could tell it would eventually leave me in pieces too shattered to mend.

There was a lot of pressure on me during those formative years from another source too—my profile as a young Christian leader. In my late teens I was already singing in front of hundreds of people at worship gatherings. As that grew to national and international exposure, the pressure increased. I was a role model—parents encouraged their kids to buy my CDs, and pastors told their youth groups to follow my example. I was terrified at the thought of disappointing them all. What if they knew who I really was? Being put on a pedestal felt as much like a prison as it did a privilege.

Year had followed year, and heartbreak had followed heartbreak as reliably as the changing of seasons. I sensed the future held more of the same, and if that was the life ahead of me, I wasn’t sure I wanted to live.

My peers were now marrying and starting families as we all progressed through our twenties. They were moving forward with their lives, celebrated at every step by their families and their faith communities—bringing a partner to church for the first time, getting engaged, getting married, announcing a pregnancy, baptizing a child. Every heterosexual social milestone was met with smiles and church ceremonies.

I felt frozen in time. No one would have celebrated my feelings, had I expressed them. No one would have celebrated my milestones if I’d gone on dates, brought a female partner to church, gotten engaged or married. For straight people, finding a spouse and starting a family were viewed as blessings from God. For anyone gay, these exact same steps were seen as sinful and something to be ashamed of.

Because of this, I’d never acted on my feelings for girls—not so much as even the briefest kiss, despite the fact I was nearing thirty. All of it was locked away inside as I tried to impeccably do the right thing by my Christian values. As I saw it, I’d chosen God instead of these attractions, pursuing holiness instead of sin. I’d boxed my feelings up and put them on a high shelf in my psyche, leaving them there—I believed—permanently. But I had no idea how deeply it would damage me.

Slowly but surely, over the years, all my emotions began shutting down and switching off, like a giant factory closing up until every machine is still and every light is out. My heart stood like an abandoned building. Empty and echoey. Uninhabited, unvisited, with doors and windows all boarded up. A monument to someone I used to be—or maybe could have been. I felt like a shell of a human being.

My life seemed a monotonous drone of work with no one to come home to. I kept my friends and family at arm’s length, because my core identity was something they couldn’t know about, and most likely wouldn’t understand. I asked my music manager to book gigs on as many holidays and special occasions as possible, so I never had to be home alone—especially on my birthday, Valentine’s Day, and New Year’s Eve. Since I was always on the go, my undecorated apartment was simply the place I did laundry, repacked my suitcase, and left again.

Weighed down by these thoughts, I stared out of the plane window as we descended into London’s Heathrow airport and taxied on the tarmac. Soon I was inside, lugging my equipment off the baggage carousel. I slung a heavy guitar case over my shoulder and wheeled a large suitcase behind me, heading toward a train bound for central London.

Fifteen minutes later, the Heathrow Express train pulled in to Paddington station. One more quick journey on the Underground, and I’d meet the conference runner who would take me to the event. The idea of stepping into the busy, upbeat energy of a worship conference felt utterly overwhelming—I had cried all night; I could barely speak, let alone sing.

On the Underground platform, the first train to arrive wasn’t going to my destination. It rushed in at breakneck speed, and I felt the whoosh of air as it sped toward me. People boarded, and then with a release of energy it sped away into the blackness of the tunnels.

I dropped my luggage next to a bench and sat with my head in my hands. My mind kept returning to the same question: “What’s the point anymore?” This frightened me to the core. I was usually a stable, balanced person, but this inner struggle with my sexuality and the incessant cycle of brokenheartedness had brought me to the point of breakdown. Embarrassed to cry in public, I tried to brush the tears away as they fell down my cheeks, but no one was watching anyway. Busy, faceless commuters stared into space, lost in their own worlds as they rushed past.

I was so incredibly tired. Every cell in my body, every fiber of my being was exhausted from carrying this emotional weight since my teens. Growing up, I hadn’t known a single gay person and had had no LGBTQ+ role models; social media didn’t exist back then in the early 1990s, so finding solace in YouTube’s coming-out advice videos—as young people do today—was a universe away from my teenage experience. I’d felt utterly isolated back then, and all these years later, I still felt the icy grip of loneliness; the passing of time only made it harder to bear.

Читать дальше