Or perhaps it’s about neurodiversity. You’re on the autistic spectrum and don’t want to mention it for fear that people will treat or think of you differently. Maybe it’s about gender roles; you might be a teenage boy who dreams of becoming a ballet dancer (like the fabulous Billy Elliot), but you’re afraid your friends (and enemies) would endlessly tease you and make life unbearable if you chased that dream.

Of course, it’s totally fine to keep these things private if it feels safer; only you know what’s right for you. Not everyone needs to “come out,” and you can be perfectly happy, healthy, and whole without taking that step. What is crucial, though, is this: we need to love and accept who we are. It’s about making peace with ourselves.

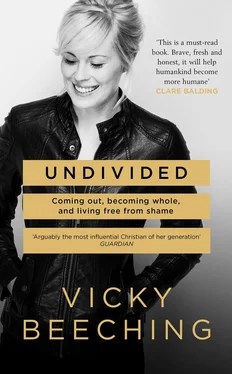

It’s about finally feeling comfortable in our own skin, not allowing others to make us ashamed or embarrassed of things that are part of our beauty, our diversity and uniqueness. When we take those pieces, shattered by shame, and dare to be ourselves, we find healing. We’re not forced to choose between aspects of our identity. We become whole and “undivided.”

Isn’t this just a bunch of selfish navel-gazing?” critics may ask.

No, it’s quite the opposite. We can only love others well when we live from a place of wholeness.

The Christian faith teaches: “Love your neighbor as you love yourself ”—the implication being that we must learn to love ourselves first, in order to love others from a place of health and well-being. Otherwise, it’s like pouring a glass of water from a broken jug; our fragmentation affects everyone.

Entrepreneur and inventor Steve Jobs, in his 2005 address at Stanford University, said, “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life … Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice … Have courage.”

He’s right. When fear and shame push us to copy the crowd, we risk living someone else’s life. Everyone loses when that happens; we won’t be the best family member, coworker, or friend we can be unless we’re authentic and whole.

So becoming “undivided” is not just about us: When we make peace with ourselves and are no longer fearful or defensive, it changes how we engage with the world . If enough of us do this, the ripple effect will go far and wide, from neighborhoods to nations.

Often, we humans run away from what we can’t relate to, from people who seem different to us. It might be someone from a different political party, a refugee from a far-flung nation, someone from a different socioeconomic background, or someone who is LGBTQ+. We build walls, bunker ourselves away, and allow stereotypes to govern the way we view the people we don’t understand. This is rife in global politics and in the church right now and requires urgent change.

Fear of the “other”—fear of the person who is different from you—is something I’ve felt personally and painfully. One moment I was seen as an insider in my evangelical Christian world; the next, I was treated as an outsider. People I’d known my entire life suddenly saw me as different, because my orientation did not match theirs. I felt their suspicion and coldness as they stepped away. They didn’t see me anymore—they just saw someone who was different from them, and they relied on broken stereotypes and judgments. Experiencing this firsthand has fueled my desire to see society change.

So, as well as becoming “undivided” on an individual level, I hope we can break down the walls that divide us societally. If we exchange our fear of others’ differences for a love that transcends stereotypes, it could have vast impact.

I’ll bring this preface to a close and let you dive into the book itself. As you read on, whoever you are and whatever the reason this book came to be in your hands, my hope for you is this: May you find the courage to be yourself in all your uniqueness. Then, free from fear and shame, may you live and love from that place of healing and wholeness.

Never underestimate the change you can bring to the world around you. Authenticity and vulnerability have a powerful domino effect. If enough of us try to live in an authentic and vulnerable way, who knows what might happen. The world could become a very different place.

Blinking in the bright lights, I stared out at twenty thousand people. The stadium was filled to capacity, and they sang along to one of my songs, “Yesterday, Today and Forever,” at the top of their lungs. I was in my late twenties and living in the US, and although I’d been recording and touring for a decade, I still treasured every time I was able to play and sing.

The volume of so many voices always takes my breath away. It sounds like a waterfall—thunderous. Crowds that big have an energy all their own, and emotion hangs in the air like a tangible mist.

I motioned to my band to bring the music down to a softer volume and, taking the microphone, I asked for the arena lights to be dimmed. I then invited the crowd to get out their phones and hold them up. Doing this creates a beautiful moment at any concert; each phone shines a tiny speck of light, and they join together to illuminate the darkness, like thousands of glowing candles, or stars in the night sky.

I’m sure all songwriters feel deeply moved when they hear people using their lyrics and melodies to express themselves—I certainly always have. It meant even more to know that people were using my songs to connect with God, as the events I played at were faith based.

I stood back, watching the sea of faces and listening to the beautiful thunder of twenty thousand voices. Every hair on the back of my neck stood on end as I captured the moment in my mind: every voice, each harmony, every sparkling light. They sang and sang, and I listened, soaking it all in. I could’ve watched them forever. It was like visiting a loved one for the last time, knowing you’ll never see that person again; you struggle to take note of all the details in an effort to ward off the inevitable dimming of the precious memory with time.

I knew that someday very soon I would lose all of this. Something in me was breaking, and I couldn’t keep going much longer. There were things I needed to say—and doing so would bring it all crumbling down.

But in that brief moment, my heart was at peace. The crowd and I were one as we sang in the darkness.

If I close my eyes, even now, I can still hear them singing.

One week after that stadium event, I sat on an overnight flight to England, headed to a Christian conference where several thousand people gathered every year. Despite trying, I hadn’t slept a wink as my mind raced with emotion. My body ached from months of touring and constant jet lag, but far more painful was my inner world: I was heartbroken because the girl I’d secretly fallen in love with had just got married.

I say secretly fallen in love with, because she never knew about my feelings—no one knew. Nobody in my life had the faintest idea that I was gay, as I’d never dared talk about it, despite the fact I was now in my late twenties. So, unknown to anyone but me, these feelings had grown the more I’d got to know this smart, vivacious, and creative American girl.

We’d become close friends over the years, so I was the first person she called when she met the guy she’d ultimately marry. I got to hear every detail of their relationship whether I wanted to or not—their first date, their first kiss, and a year later the evening he got on one knee and proposed. Wanting to be a good friend to her, I’d been there to watch the couple walk down the aisle in a New York church. As they drove off at the end, headed for their honeymoon, my heart was shattered at the loss.

Читать дальше