It was in this little hut, with its tilting floor, that on my first day of school I answered the register by calling out ‘Yes, Mummy’, and shortly afterwards wet myself; the water trickled slowly down the slope to the back of the classroom. I was not easily reconciled to leaving home: no sooner had my mother put me on the bus in the morning than I got off at the next stop and promptly walked back again. An ex-police station, a military hut and open air toilets did little to allay the fears of a knock-kneed boy in a home-knitted green jumper and grey shorts; still less an elderly teacher with an iron calliper on her leg.

In our tin classroom we would dutifully copy out Miss Clements’ copperplate writing from the blackboard, dipping our nibs in china inkwells filled by the ink monitor from a giant bottle of Quink, inevitably staining our fingers and our shirts dark blue. We recited our times tables, and on Wednesday mornings we’d file next door for Mass in the big ‘new’ church, built in 1939 (and promptly gutted by incendiary bombs in 1940). Now refurbished, with its green stained-glass windows, a stone statue of St Patrick over the entrance and, inside, another huge portrait of the saint driving the serpents out of Ireland, it was as invested with Irishness as were our green school uniforms and the bunches of shamrock which would mysteriously arrive from Ireland on St Patrick’s Day. They were symbols of a statehood I did not share, except by the association of faith, and, somewhere in my green eyes, the faint traces of a genetic Irishness.

Class by class we’d troop across a parquet floor dented by a decade of Sixties stilettos, file into our seats and pull down the kneelers. Crouching, I’d look through my fingers to the wounded, contorted figure of Christ above the altar, and the glass mosaics on either side, art deco versions of Byzantine icons. On one side, Jesus pointed to the exposed and radiant heart, red and glowing in His chest; on the other, in front of me, was the Blessed Virgin, her oval face surrounded by a gold tesseral halo. Like her grown-up son, her body lay full length against the wall, floating in space and impossibly attenuated; but in the folds of her transcendent blue gown she clasped an unwounded and perfectly formed Christ Child holding up His baby hand in blessing. Sometimes, as I stared, I felt I too could float into the air, to be suspended above the congregation, to the amazement of my fellow pupils. At the end of term we would return for Benediction and its Latin litany intoned in clouds of intoxicating incense, and on May Day we would process through the church gardens behind a statue of Our Lady carried on a wooden stretcher, her beautiful neat head crowned with a garland of flowers as we sang, ‘Ave, ave, ave Maria’.

One dinnertime I ran down to the school gate to see my father arrive in the big old family car with my beaming little sister, her brown hair in bunches, not yet old enough for school, jumping excitedly up and down on the passenger seat. We drove home to see our new baby sister, pink and bawling in crocheted wool and carry cot by my mother’s bedroom window. She was as blonde as my elder sister was dark; they were a perfect pair, and I loved them and they loved me. The world seemed as safe and secure as our new baby swaddled in her cot, her tiny fingers clasping the wool like soft pink bird’s talons. I read the Beano on my father’s knee on dark winter evenings and he cut my finger- and toenails.

The house was yellow and warm, but one day I came home from school to find my mother airing clothes on a wooden clothes horse in front of the coal fire, upset by the news she had just heard on our old valve radio (with its illuminated dial and place names as strange as the lunchtime shipping forecast). Many children had died after a mountain of coal had fallen on their school in Wales. Later, on TV, there would be grainy black and white images of a destroyed building in a mining village, and men in coats picking over what looked like a bomb site. In my mind’s eye I saw the black soot engulfing the high ceilings of my classroom, pouring in through the big wide window, silently crashing and crushing. *

But mostly life and death carried on over my pudding-basin-haircut head. I went to school as the sun rose at one end of the street, and went to bed as it set at the other. I saw my first streak of lightning make an electrified crack in the sky, and ran home for cover. I played soldiers and feared hospitals, and once visited the dentist’s in an Edwardian house opposite our school to have a tooth pulled out. In grey shorts, another green home-knitted jumper, and a permanent scab on my knees, I saw the brass plate at the entrance, the venetian blinds at the windows, the unadorned front garden: all too neat, too clean, too white to be a home. I panicked as the black rubber mask descended, halo’d by the yellowy examination light that shone on the steel instruments laid out in a tray at my shoulder. The nauseous smell of the rubber was pressed down on my memory with the hiss of the gas as it was clamped over my small face, the dentist’s white coat and stubble and glasses above. The next thing I remember was staggering out of the porch, spitting gobs of gelatinous blood like leeches, reeling on to the front lawn and lying there, the world turning above me as I experienced my first intoxication, mixed with medically-induced pain from a suburban house of torture.

If these were the worst things in my life, the rest of it must have been pretty good. But then everything changed.

It was a Saturday morning. I remember coming downstairs and looking over the banisters – another aerial view, as if I were removed from these proceedings in my life, these out-of-body experiences – and watching my parents moving about in the front room. They were not doing the housework; they were not moving in the way parents should move.

My brother had been injured in a car crash. He was twenty-three years old. After a week in a coma, my mother and his young wife staying at the hospital to be at his bedside, Andrew died.

The news permeated the house like an invisible gas. I remember being told about it while standing by the kitchen door; I knew it had happened, but I must have appeared as if I didn’t. Crouching down to my eleven-year-old level, my brother explained in slow, clear tones that Andrew was dead. ‘I know’, I said, and ran out, down to the bottom of the garden, where the snakes hid in the privet hedge.

Everything seemed thrown in the air, as though the atmosphere itself had buckled and warped. Nothing was right; everything was wrong. It was almost exhilarating, as though you were moving backwards at speed, removed from the events that were taking place, that you knew you were witnessing and yet could not feel.

Later, I tried to access the emotion I should have felt. I tried to remember Andrew, with his thick, dark spiky hair and round head, shaped like mine, and which my parents said was as hard as a bullet. I thought of his kind face, his stocky body, his sports shirt, the tinned steak and kidney puddings he sold from the back of his van, even though he was a vegetarian. But all I could remember was the day he took my sister up to the corner shop and filled her dolls’ pram full of sweets for her birthday. For that act alone he was a hero. He became the lost connexion that would have made the rest of my life happy.

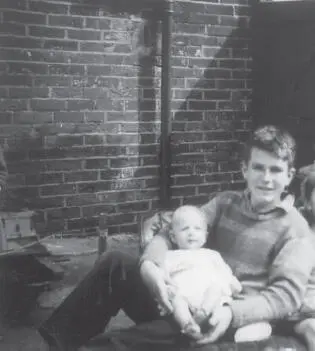

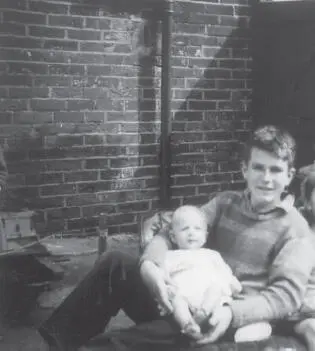

In the back garden of Akaba, sitting against a brick wall, my dead brother cradles me proudly in his strong arms, my plump little baby’s fingers in his. He grins at Dad’s camera, his arms full of me: pale and pudgy, I look straight ahead, eyes unfocused, nonplussed, still vaguely embryonic, as though I’d only just emerged into the world. Over in our new suburban home, with its smaller rooms and without my brother’s wide arms, I would grow like a goldfish grows to the size of its bowl; knees bent as I crouched by the gas fire in grey wool dressing gown tied with a twirly cord, chilblains on my feet in winter, burning ginger biscuits in front of the ash-white ceramic that glowed luminous red with internal heat as the wind whistled up the chimney.

Читать дальше