Adventures in a Victorian Utopia

For Mark

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

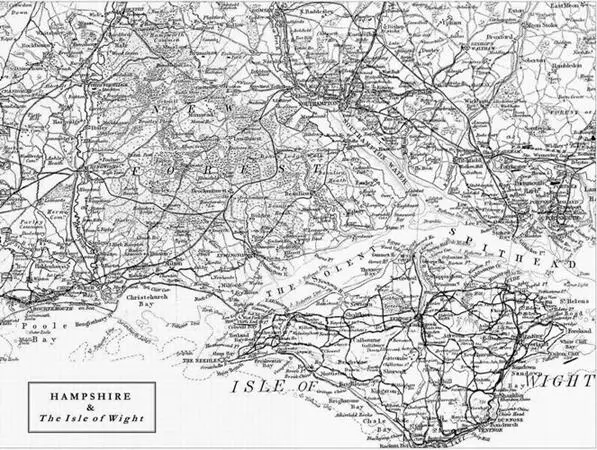

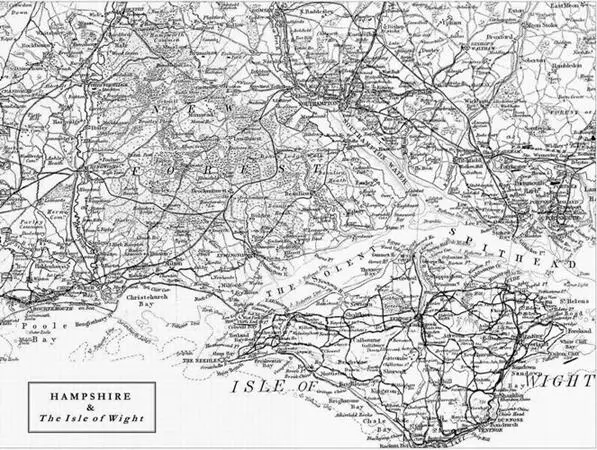

Map

Prologue : A place of royal death

PART I: Green and Pleasant Land

1 A Voice in the Wilderness

Into the forest; Mary Ann’s life & visions in Suffolk; the Girlingites’ debut

2 Turning the World Upside-Down

Bunhill Fields & the Camisards; Ann Lee & the Shakers; American utopias

3 Human Nature

Elder Evans & James Burns; Human Nature & spirit photography; the mission to Mount Lebanon

PART II O Clouds Unfold!

4 The Walworth Jumpers

Sects, spiritualism, & Swedenborg; Mary Ann at the Elephant & Castle

5 The New Forest Shakers

Hordle, the Girlingites’ heyday; Peterson & his mesmeric experiments

6 The Dark and Trying Hour

Eviction & despair; Mary Ann examined on the condition of her mind

PART III Arrows of Desire

7 The Sphere of Love

Broadlands & the Cowpers; Rossetti & Beata Beatrix ; Myers & Gurney; the Broadlands Conferences

8 The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century

Ruskin & the Spiritualists, the Guild of St George & Fors Clavigera ; Brantwood

9 The Names of Butterflies

Rose La Touche, Broadlands & the spirits

PART IV The Countenance Divine

10 This Muddy Eden

Isaac Batho’s mission; Auberon Herbert & naked dancing; Julia Wood interned; Girlingites on tour

11 Mr Peterson’s Tower

A.T.T.P. & Wm Lawrence, pet medium; the tower rises

12 The Close of the Dispensation

The Census; the rival ‘Mother’; Mary Ann’s stigmata

PART V A New Jerusalem

13 In Borderland

Laurence Housman & ‘Jump-to-Glory Jane’; Herbert & Theosophy; Ruskin’s last days; Georgiana & the Wildes; The Sheepfold

14 Resurgam

The quest for Mary Ann & her followers; Peterson’s transition

Epilogue : The forest once more

Source and Bibliographical Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Early in May 1100 – the exact date is uncertain – the king’s bastard nephew was hunting deer in the New Forest when he was killed by an arrow loosed by one of his own party. Thirty years before, his uncle, the king’s brother, had been gored to death by a stag in the same forest. Both deaths were seen as a judgement on the Norman invaders who had imposed their rule on the land, sweeping aside entire villages to create a vast hunting ground, a kind of royal Eden. An elderly victim of that enclosure cursed the reigning family, predicting their demise within its woods; and so when, later that fateful year, a stray arrow claimed the life of the king himself, it was seen as a death foretold, an ironic end for a man whose father had claimed to love deer more than his own flesh and blood.

William Rufus, forty-year-old son of the Conqueror, was named after his florid complexion rather than his hair, which was flaxen like that of his Viking ancestors. Rufus had ruled England for thirteen years: a fair-minded king to many, but to others, especially the Church, his rival in temporal power, a godless man of pagan leanings. Some called him a warlock; others accused Rufus of the more worldly vice of sodomy. In that last year, the Devil appeared to men ‘in the woods and secret places, whispering to them as they passed’. One bishop exiled by the king saw him in a vision, condemned to the fires of Hell.

In his final hours, these stories began to accelerate around Rufus, as though the forest itself were closing in upon him. As day broke on the morning of 2 August 1100, a monk appeared before the hunting party, relating a dream in which the king had swaggered into a church and seized the crucifix from its altar, tearing its arms and legs ‘like a beast … with his bare teeth’. The cross had hurled its assailant to the ground, and ‘great tongues of flame, reminiscent of the stream of blood, spurted from his mouth and reached towards the sky’. Later that day, the Earl of Cranborne went out hunting and met a black goat with the body of a naked, wounded man on its back. The animal said it was the Devil, crying, ‘I bear to judgement your King, or rather your tyrant, William Rufus. For I am a malevolent spirit and the avenger of his wickedness which raged against the Church of Christ and so I have procured his death.’

Disconcerted by these portents, Rufus delayed his sport until the evening. Riding with the king’s hunting party was his brother Henry, Walter Tirel of Poix, and other powerful men, jangling arrogantly through a forest they regarded as their private domain. The deer were to be driven towards them and, accordingly, a stag entered the clearing in which the king waited, the long shadows of the summer’s evening cast before him. It was as if the entire affair were choreographed and lit to give it theatricality; shielding his eyes from the rays of the setting sun, Rufus loosed his arrow. As he watched the animal stagger, another appeared, distracting the king’s attention, and ‘at this instant Walter … unknowingly, and without power to prevent it, Oh gracious God! pierced his breast with a fatal arrow. On receiving the wound, the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the weapon where it projected from his body, fell upon the wound, by which he accelerated his death.’

The horror of the scene – played out in slow-motion, as it were – was counterpointed by its setting: the silent beauty of the glade, the swift arrow seeking its pre-ordained target, the venal king falling to the forest floor. It was a death given transcendence by its victim’s sovereignty, and by the reaction of the royal body to the arrow’s penetration, by which he accelerated his death . And in the multiple perspective of historical record, the act acquired other meanings, as though filmed by another camera. It was claimed that the arrow was aimed away from the king, but was deflected by an oak tree, while others discerned conspiracy at work among those with rival claims to the throne. Over the next millennium, myth and legend gathered round this royal assassination. Some saw Rufus as ‘the Divine Victim, giver of fertility to his kingdom’, killed on the morrow of the pagan feast of Lammas in order to propitiate the gods. The notion of ritual sacrifice linked William Rufus’s murder with that of Thomas à Becket; with witchcraft, Cathar heresy and Uranianism – ‘the persistence of “unnatural love” as a mark of the heresy’. To others, however, the king’s demise was just ‘a stupid and an accidental death’.

Читать дальше