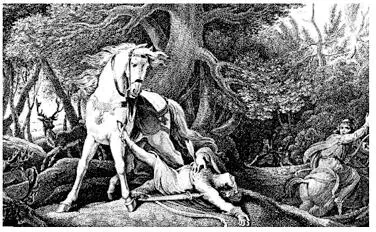

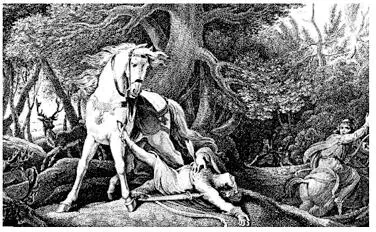

The oaks still stand that witnessed these deeds, although their hearts have been eaten away by fungus as old as the wood itself, leaving hollow crowns, shadows of their living selves. In the eighteenth century, a stone was erected where Rufus fell, although even this site, near Minstead, was disputed, as if elusive myth rejected hard fact. Here, it was said, a ghostly hart would appear at times of national crises and, like King Arthur sleeping in Avalon, Rufus would wake and fight for his country. The spectral animal was sighted during the Crimean War, again in 1914, and on the eve of the deaths of George IV and Edward VII. It has yet to be seen again.

Leaving Southampton, westwards, monstrous cranes straddle the estuary’s upper reaches, where mudflats meet the industrial port on land reclaimed from the sea. The dock wharves are strewn with tank-like containers and row after row of brand new cars awaiting export, shiny from the production line. Electric pylons stalk across this confluence of water and land, while herons pick their way gracefully through the mud and ponies perch on the grassy bank of the dual carriageway, their bodies improbably tilted at right angles to the busy road. In high summer, daredevil lads balance on the old stone bridge beneath the flyover, yanking off their shirts and jumping into the water, the brief arch of their leap caught in freeze-frame by the cars speeding overhead.

I once flew over this interzone in a balloon, rising noiselessly from the city’s common at dawn, borne up by a raw flame roaring under the neon nylon tent which billowed between us and infinity. Our wickerwork cradle creaked as we were lifted into the sky and over the park, its green carpet falling away as we sailed silently into the air, bumping with the unseen thermals. We drifted over the Civic Centre and its needle tower, built to emulate an Italian campanile, and over the port in whose great dry docks ocean liners were once prised out of their element like stranded cetaceans while workers examined their barnacled hulls. Southampton Water opened out ahead, and in the distance, on an horizon below rather than level with the eye, the Solent and its fluttering yachts held the Isle of Wight in a silvery embrace.

For a brief moment, in the hour after dawn, we were caught out of time and space, suspended above the world and the suburban plots whose tenants were just beginning to surface that Saturday morning, waking to see our airy leviathan floating noiselessly over their heads. In that moment ordinary life stopped: all that was below had been disconnected as the lines between us and the earth snapped as we had tugged away from the field and pulled up the anchor. Now we were left to nothingness, in limbo, supported by no more than a thin layer of fabric as we hung in mid-air, dangling like puppets.

Then, just as imperceptibly as we had gained this strangely unvertiginous height, the great sphere above us began to lose its tautness. The crimson licking flame diminished, and slowly, with pathetic gasps, the heat and air began to go out of our inflated world. The wind caught us, and we went with it, gliding past the military port at Marchwood and its ordered terrain, then dipping over the wetlands as the ground rushed up to meet us faster and faster until, ordered into landing positions, we crouched down in the basket, backs braced, knees drawn up to our chests like parachutists ready to return to earth. Through the willow-woven cracks, the bright light was dimmed by approaching land. Suddenly we hit the grass, ripping up clods and biting into the field before dragging to a violent halt, our bodies tossed about in the basket like so much fruit. We climbed out on uncertain legs, as though we’d experienced zero gravity and had to reaccustom ourselves to firm ground. But we really were in another world, for we had flown free of the city and into the forest itself.

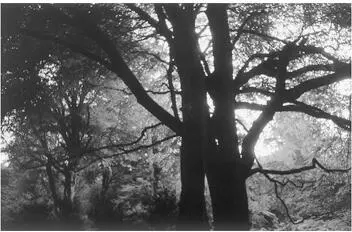

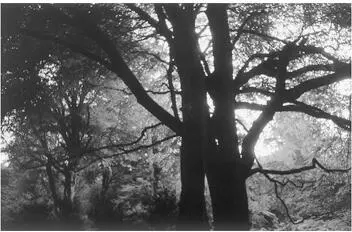

Walking into the woods is like entering a rainforest. In the stillness, which isn’t still at all, birds sing and boughs sigh, unseen in the translucent green canopy above, which filters a subaqueous light. The world is dampened here, muffled by brilliant green moss and held in by sinuous roots, as though the earth were bursting with its own fertility. The forest floor clings to the feet, the senses heightened by the silence; intensely aware of cracking twigs and rustling leaves and rotting vegetation dragged down into the soil by worms and beetles, adding another layer to this fecund, decaying, self-regenerating organism. You must tread carefully here, for you are walking on the living and the dead.

Once all of England looked like this; even a thousand years after its enclosure, the New Forest still feels medieval: an ancient domain which ought not to exist at all, and which, ironically, owes its preservation to an invader. It has no physical boundaries to mark its beginning or its end, and yet it encompasses a third of Hampshire. It is barely an hour and a half’s drive from London, but it is a liminal region, for all its apparent accessibility. In the Dark Ages, this was one of the last parts of the country to remain pagan; in the Second World War, witches gathered here to ward off an invasion force invested with its own occult beliefs. This place of purity has ever been suffused with the alien: from the Romans and the Vikings, to whom I owe the kink in my little finger, to the gypsies who first came here from Europe five hundred years ago, and who until recently sent their children to school wearing rabbit-skins under their clothes.

Even its name is deceptive – ‘forest’ was the word for a hunting ground, rather than woods – and modern visitors wonder where all the trees are. For mile after mile, the eye sees nothing but great stretches of heathland flattened by the sky: the spaces where the woods once were. Calluna vulgaris and Ulex europaeus – the pink-belled heather and the coconut-scented gorse – colonise these gravelly expanses with relentless efficiency. These are tough, hard-bitten plants used to the hooves of the ponies that congregate idly on the verges, their thick hides, shaggy manes and round bellies stolid and unmoving as their big black eyes reflect the cars which occasionally cull one of their number, each sweet stupid victim awaiting its turn.

Yet for all its contradictions, or perhaps because of them, the forest is a compendium of myth. It reaches back to an age before the cruel Norman laws which would amputate the fingers of poachers and mutilate their dogs’ feet, to dark woods peopled by Herne the Hunter, a man in stag’s guise, his antlers ‘spreading like mantling in the breeze’; and to the wise wild men, strange figures part way between animal, vegetable and human who had their Victorian counterpart in Brusher Mills, the snake-catcher who allowed his reptiles to slither through his beard.

A place where the pagan worship of trees conflated with the verdant cross of Christian immortality, ever subject to the immemorial cycle of life, death and resurrection, this new-old forest stands for all threatened wildernesses. It promises a sylvan idyll, the greenwood of all our imaginings, invested with certainty and superstition, hope and fear; a place of sanctuary, mystery and magical transformation, here in the heart of England, our lost and ancient Eden.

Читать дальше

Читать дальше