But what was alchemy? The familiar response is that it involved the pursuit of the transmutation of base metals such as lead into gold. In practice, the aims of the alchemist were often a good deal broader, and it is only because we take a false perspective in seeing chemistry as arising from alchemy that we normally narrowly focus on to alchemy’s concern with the transformation of metals. However, as Carl Jung pointed out in his study Psychology and Alchemy , there are similarities between the emblems, symbols and drawings used in European alchemy and the dreams of ordinary twentieth-century people. One does not have to believe in psychoanalysis or Jungism to see that the most obvious explanation for this is that alchemical activities were often concerned with a spiritual quest by humankind to make sense of the universe. It follows that alchemy could have taken different forms in different cultures at different times.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, after the elderly French chemist, Marcellin Berthelot, had made available French translations of a number of Greek alchemical texts, an American chemist, Arthur J. Hopkins (1864–1939), showed how they could be interpreted as practical procedures involving dyeing and a series of colour changes. He was able to show how Greek alchemists, influenced by Greek philosophy and the practical knowledge of dyers, metallurgists and pharmacists, had followed out three distinctive transmutation procedures, which involved either tincturing metals or alloys with gold (as described in the Leiden and Stockholm papyri), or chemically manipulating a ‘prime matter’ mixture of lead, tin, copper and iron through a series of black, white, yellow and purple stages (which Hopkins was able to replicate in the laboratory), or, as in the surviving fragments of Mary the Jewess, using sublimating sulphur to colour lead and copper.

While Hopkins’ explanation of alchemical procedures has formed the basis of all subsequent historical work on early alchemical texts, and while Jung’s psychological interpretation has stimulated interest in alchemical language and symbolism, it was the work of the historian of religion, Mircea Eliade (1907–86), who, following studies of contemporary metallurgical practices of primitive peoples in the 1920s, firmly placed alchemy in the context of anthropology and myth in Forgerons et Alchimistes (1956).

These three twentieth-century interpretations of alchemy, dyeing, psychological individuation and anthropology, together with the historical investigation of Chinese alchemy being undertaken by Joseph Needham and Nathan Sivin in the 1960s, stimulated the late Harry Sheppard to devise a broad definition of the nature of alchemy 3 :

Alchemy is a cosmic art by which parts of that cosmos – the mineral and animal parts – can be liberated from their temporal existence and attain states of perfection, gold in the case of minerals, and for humans, longevity, immortality, and finally redemption. Such transformations can be brought about on the one hand, by the use of a material substance such as ‘the philosopher’s stone’ or elixir, or, on the other hand, by revelatory knowledge or psychological enlightenment.

The merit of such a general definition is not only that it makes it clear that there were two kinds of alchemical activity, the exoteric or material and the esoteric or spiritual, which could be pursued separately or together, but that time was a significant element in alchemy’s practices and rituals. Both material and spiritual perfection take time to achieve or acquire, albeit the alchemist might discover methods whereby these temporal processes could be speeded up. As Ben Jonson’s Subtle says in The Alchemist , ‘The same we say of Lead and other Metals, which would be Gold, if they had the time.’ And in a final sense, the definition implies that, for the alchemist, the attainment of the goals of material, and/or spiritual, perfection will mean a release from time itself: materially through riches and the attainment of independence from worldly economic cares, and spiritually by the achievement of immortality.

The definition also helps us to understand the relationship between the alchemies of different cultures. Although some historians have looked for a singular, unique origin for alchemy, which then diffused geographically into other cultures, most historians now accept that alchemy arose in various (perhaps all?) early cultures. For example, all cultures that developed a metallurgy, whether in Siberia, Indonesia or Africa, appear to have developed mythologies that explained the presence of metals within the earth in terms of their generation and growth. Like embryos, metals grew in the womb of mother Nature. The work of the early metallurgical artisan had an obstetrical character, being accompanied by rituals that may well have had their parallel in those that accompanied childbirth. Such a model of universal origin need not rule out later linkages and influences. The idea of the elixir of life, for example, which is found prominently in Indian and Chinese alchemy, but not in Greek alchemy, was probably diffused to fourteenth-century Europe through Arabic alchemy. The biochemist and Sinologist, Joseph Needham, has called the belief and practice of using botanical, zoological, mineralogical and chemical knowledge to prepare drugs or elixirs ‘macrobiotics’, and has found considerable evidence that the Chinese were able to extract steroid preparations from urine.

Alongside macrobiotics, Needham has identified two other operational concepts found in alchemical practice throughout the world, aurifiction and aurifaction. Aurifiction, or gold-faking, which is the imitation of gold or other precious materials – whether as deliberate deception or not depending upon the circumstances (compare modern synthetic products) – is associated with technicians and artisans. Aurifaction, or gold-making, is ‘the belief that it is possible to make gold (or “a gold”, or an artificial “gold”) indistinguishable from or as good as (if not better than) natural gold, from other different substances’. This, Needham suggests, tended to be the conviction of natural philosophers rather than artisans. The former, coming from a different social class than the aurifictors, either knew nothing of the assaying tests for gold, or jewellery, or rejected their validity.

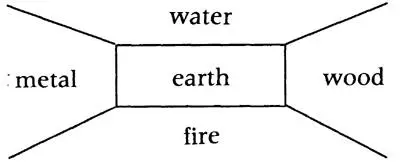

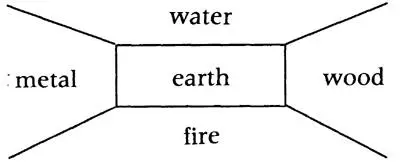

Aurifactional alchemical ideas and practices were prevalent as early as the fourth century BC in China and were greatly influenced by the Taoist religion and philosophy devised by Lao Tzu ( c. 600 BC) and embodied in his Tao Te Ching ( The Way of Life ). Like the later Stoics, Taoism conceived the universe in terms of opposites: the male, positive, hot and light principle, ‘Yang’; and the female, negative, cool and dark principle, ‘Yin’. The struggle between these two forces generated the five elements, water, fire, earth, wood and metal, from which all things were made:

Unlike later Greco-Egyptian alchemy, however, the Chinese were far less concerned with preparing gold from inferior metals than in preparing ‘elixirs’ that would bring the human body into a state of perfection and harmony with the universe so that immortality was achieved. In Taoist theory this required the adjustment of the proportions of Yin and Yang in the body. This could be achieved practically by preparing elixirs from substances rich in Yang, such as red-blooded cinnabar (mercuric sulphide), gold and its salts, or jade. This doctrine led to careful empirical studies of chemical reactions, from which followed such useful discoveries as gunpowder – a reaction between Yin-rich saltpetre and Yang-rich sulphur – fermentation industries and medicines that, according to Needham, must have been rich in sexual hormones. As in western alchemy, Taoist alchemy soon became surrounded by ritual and was more of an esoteric discipline than a practical laboratory art.

Читать дальше