Helmont’s tree leads us both backwards and forwards in time – forwards to when evidence accrued that air (and gases) did participate in chemical change, and backwards to the ancient traditions of elements and of transmutation that Helmut had inherited. The book opens with the roots of chemistry and the social, economic and religious environments that promoted it before the time of Helmont. In particular, the opening chapter examines early chemical technologies and their rationalization by Greek philosophers in theories of elements or, more iconoclastically, in terms of corpuscules and atoms. The tree enters here again, for one of the perennial proofs for the existence of elements and for their number was the destructive distillation of wood by fire – an important phenomenon empirically (for it was the model for distillation techniques generally) and cognitively because it was the basis of the concepts of analysis and synthesis. Chemistry was, and is, concerned with the analysis of substances into their elements and the synthesis of substances from their elements or immediate principles.

The possibility of manipulating elementary matter into substances of commercial or – at the extreme – of spiritually uplifting value, such as silver and gold or an elixir of life, led to alchemy. The latter’s origin, as well as its formal connections with chemistry, are complex and even contentious. However, our contemporary demand for science to have empirical validation, as well as our respect for the technological manipulation of Nature’s resources for the benefit of humankind, can be traced back to the philosophical spirit of enquiry that underpinned alchemical investigations. And it goes without saying that alchemy provided early chemistry with much of its apparatus and manipulative techniques, as well as the idea of a formal symbolic language for practitioners of the art.

Each of the sciences, no doubt, has its own difficulties and peculiarities when it comes to presenting its historical development to a diverse audience of professional historians, scientists, students and laypersons; but chemistry, like mathematics, possesses a particularly intimidating obstacle in its language and symbolism, which potentially obscures what are usually quite simple theoretical ideas and experimental techniques. As William Crookes noted in 1865 when reviewing a book on stuttering that had been inappropriately sent to Chemical News for review:

Chemists do not usually stutter. It would be very awkward if they did, seeing that they have at times to get out such words as methylethylamylophenylium.

However, if (as Peter Morris has noted) the historian avoids chemical detail and language, the scientific story become exigious and almost trivial. For this reason, while the first twelve chapters should present little difficulty to a sophisticated general reader, I have not hesitated to use technical language in the five chapters that are devoted to twentieth-century chemistry. Because this is a history, and not a textbook, of chemistry, I have not defined and explained symbols, equations and technical vocabulary. These chapters will present little difficulty to readers who have a secondary or high-school foundation in chemistry (and will have the privilege of being critical of my treatment). At the same time, it is to be hoped that there is sufficient of a human interest story in the intellectual and experimental worlds of Pauling, Ingold, Nyholm, Woodward and the other giants of twentieth-century chemistry, to propel the non-chemical reader towards the final pages.

The history of chemistry has served and continues to serve many purposes: didactic and pedagogic, professional and defensive, patriotic and nationalistic, liberalizing and humanizing. As I write, especially in America, where words like ‘chemical’, ‘synthetic’ and ‘additive’ have unfortunately become associated with the pollution, poisoning and disasters caused by humans, the history of chemistry has come to be seen by leaders of chemical industry and educators as a possible way of revaluing chemical currency: that is, of demonstrating not only the ways in which chemistry plays a fundamental role in nature and our understanding of cosmic processes, but also how it is essential to the economy of twentieth-century societies. In other words, the history of chemistry not only informs us about our great chemical heritage, but justifies the future of chemistry itself. Such a justification echoes the liberal and moving words of the first major historian of chemistry, Hermann Kopp 1 :

The alchemists of past centuries tried hard to make the elixir of life … These efforts were in vain; it is not in our power to obtain the experiences and views of the future by prolonging our lives forward in this direction. However, it is possible and in a certain way to prolong our lives backwards, by acquiring the experiences of those who existed before us and by learning to know their views as if we were their contemporaries. The means for doing this is also an elixir of life.

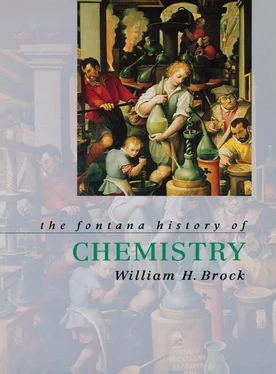

It is in this spirit that The Fontana History of Chemistry has been written.

1 On the Nature of the Universe and the Hermetic Museum

Maistryefull merveylous and Archimastrye Is the tincture of holy Alkimy;

A wonderful Science, secrete Philosophie,

A singular grace and gifte of th’Almightie:

Which never was found by labour of Mann,

But it by Teaching, or by Revalacion begann.

(THOMAS NORTON, The Ordinall of Alchemy, c. 1477)

In 1477, having succeeded after years of study in preparing both the Great Red Elixir and the Elixir of Life, only to have them stolen from him, Thomas Norton of Bristol composed the lively early English poem, The Ordinall of Alchemy. Here he expounded in an orderly fashion the procedures to be adopted in the alchemical process, just as an Ordinal lists chronologically the order of the Church’s liturgy for the year. Unfortunately, although the reader learns much of would-be alchemists’ mistakes, and of the ingredients and apparatus, of the subtle and gross works, and of the financial backing, workers and astrological signs needed to conduct the ‘Great Work’ successfully, the secret of transmutation remains tantalisingly obscure.

The historian Herbert Butterfield once dismissed historians of alchemy as ‘tinctured with the kind of lunacy they set out to describe’; for this reason, he thought, it was impossible to discover the actual state of things alchemical. Nineteenth-century chemists were less embarrassed by the subject. Justus von Liebig, for example, used the following notes to open his Giessen lecture course:

Distinction between today’s method of investigating nature from that in olden times. History of chemistry, especially alchemy …

Liebig’s presumption, still widespread, was that alchemy was the precursor of chemistry and that modern chemistry arose from a rather dubious, if colourful, past 1 :

The most lively imagination is not capable of devising a thought which could have acted more powerfully and constantly on the minds and faculties of men, than that very idea of the Philosopher’s Stone. Without this idea, chemistry would not now stand in its present perfection …[for] in order to know that the Philosopher’s Stone did not really exist, it was indispensable that every substance accessible … should be observed and examined.

To most nineteenth-century chemists, and historians and novelists, alchemy had been a human aberration, and the task of the historian seemed to be to sift the wheat from the chaff and to discuss only those alchemical views (chiefly practical) that had contributed positively to the development of scientific chemistry. As one historiographer of the subject has put it 2 :

[the historian] merely split open the fruit to get the seeds, which were for him the only things of value. In the fruit as a whole, its shape, colour, and smell, he had no interest.

Читать дальше