Doctor Who’s Dutch cousin

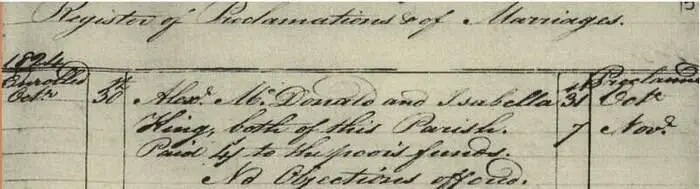

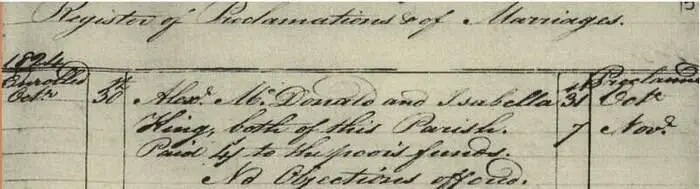

TOP: The marriage proclamation of David Tennant’s great-great-great-grand parents in 1824 reads: Alexr McDonald and Isabella King, both of this Parish, Paid 4s/ to the poor’s funds. No Objections offered Proclaimed 31st Octr 7 Novr This entry employs a number of abbreviations, for the months and also Alexander’s name. It was found on the ScotlandsPeople website, but only after using the Soundex option (see p. 49), as he was indexed as ‘Alexr’, not ‘Alexander’.

LEFT: David Tennant.

Joining a contact website such as Genes Reunited is seldom a waste of effort. Kenny Graham, who lives in the Netherlands, had been tracing his mother’s MacDonald family tree since about 1990, and a few years ago put it on Genes Reunited. His children never took much interest in it until an email arrived from me. ‘Suddenly,’ wrote Kenny, ‘Daddy’s “boring” hobby became cool.’

I was tracing the family tree of David Tennant, the West Lothian-born actor who is the latest incarnation of science fiction hero Doctor Who. David’s real name is David MacDonald. His father, Alexander, Moderator of the Church of Scotland, was the great-grandson of John MacDonald, son of Alexander MacDonald, a road labourer at Kilmadock, who married Isabella King at Lecropt, Co. Perth, in 1824.

I wanted to see if David had any relatives out there, so I looked these ancestors up on Genes Reunited, and found their names had been entered by Kenny, whose great-great-grandfather Peter MacDonald was another son of Alexander and Isabella’s.

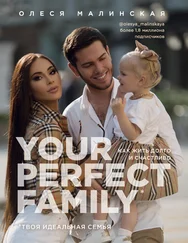

‘I couldn’t believe it when we got the email,’ said Kenny, ‘because it is not every day you find out that David Tennant is your fourth cousin!’ His son Ben, nine, was even more excited: ‘When I told my friends a few believed me but most of them didn’t. It seems a bit different watching David on TV now because I try to imagine what he is like in real life.’ His sister Kirsty, aged seven, said, ‘I was really surprised when I found out. My friends didn’t believe me but when they found out it was true they were amazed. My friends and I made a Doctor Who Club at school where we talk about the last episode.’ Kenny told me that ‘this experience has helped us greatly in keeping the children aware of their “Scottishness” and also brought to life my hobby to my siblings.’

RIGHT: The Graham family (courtesy of K. Graham).

Original records are usually held in the archives of the organization that created them, or in public repositories, local or national. As it is not always practical to visit an archive, there are other options:

1.The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also called the Mormon Church, has an ever-growing archive of microfilm copies of original records from all over the world, including Scotland, many of which are indexed on the Mormon website www.familysearch.org.Founded in 1830, the Utah-based church has a religious mission to trace all family trees, and they hold ceremonies that allow the deceased to become Mormons, should their souls desire. They have Family History Centres (FHCs) in most major towns: find your nearest at www.familysearch.org.FHCs are open to all – entirely without any compunction to convert – and here you can order any microfilms to be delivered from the Mormon’s Family History Library in Utah.

2.Many Scottish records have been published, as indicated where appropriate in this book, especially by the Scottish History Society (SHS) www.scottishhistorysociety.organd the Scottish Record Society (SRS) www.scottishrecordsociety.org.Volumes can be bought, examined in genealogical libraries, or ordered through interlibrary loan.

General Register House, Princes Street, Edinburgh, where the ScotlandsPeople Centre is housed.

3.You can hire a genealogist or record agent. Genealogists like myself charge higher fees and organize and implement all aspects of genealogical research. Record agents charge less and work to their clients’ specific instructions, for example: ‘Please list all Colquhouns in the Old Parochial Registers of Oban between 1730 and 1790’. Most archives have a search service, or a list of local researchers. Many advertise in genealogy magazines or at www.genealogypro.com, www.expertgenealogy.comand www.cyndislist.org, and some belong to the Association of Scottish Genealogists and Researchers in Archives, www.asgra.co.uk, whose members charge a minimum rate of £20 per hour, though membership does not guarantee quality. The NAS website has links to some genealogists on www.nas.gov.uk/doingResearch/remotely.asp.

Most professionals are trustworthy, and many offer excellent services, though ability varies enormously. Generally, the more prompt and professional the response, and neater the results, the more likely they are to be any good. Hiring help is not ‘cheating’: if you only want one record examined but are not sure it will contain your ancestor, it makes no sense to undertake a long journey when you can pay someone a small fee for checking for you, and a local searcher’s expertise may then point you in the right direction anyway.

4.By using the ScotlandsPeople Centre in Edinburgh and its website. In the ‘Old Days’, the only way to trace Scottish family history was to go to New Register House, Edinburgh, and search the indexes to births, marriages and deaths (from 1855), and the censuses (currently from 1841 to 1901), and then walk round to the National Archives of Scotland to examine the Old Parochial Registers (that can go back to the 1500s) and testaments (also from the 1500s).

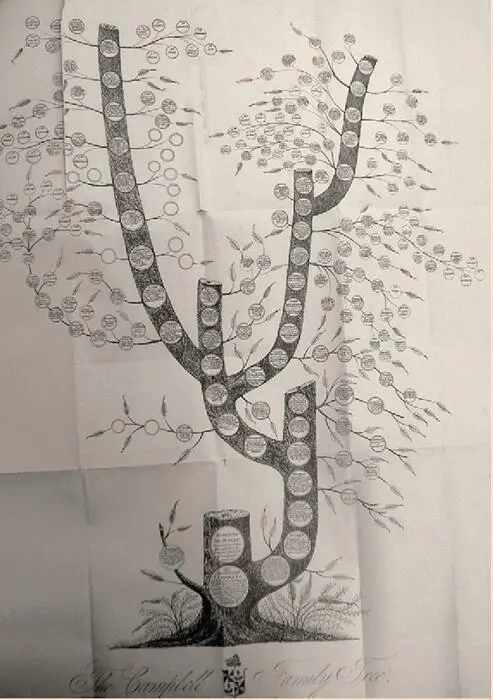

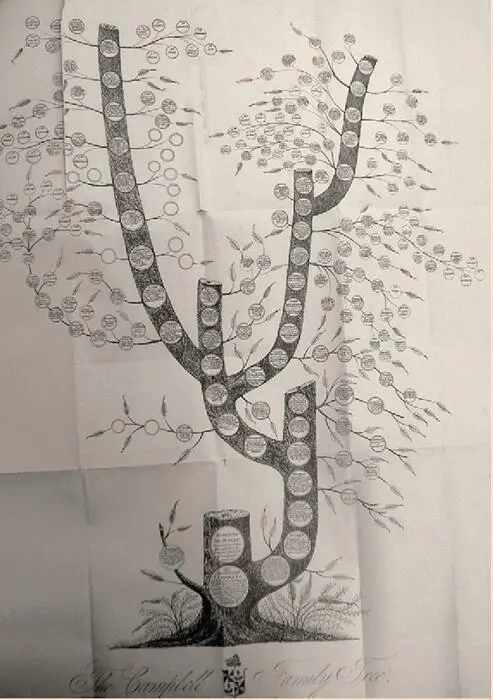

A family tree of the Campbell Clan, drawn as a real tree, complete with trunk and branches, from The House of Argyll and the Collateral Branches of Clan Campbell (1871) – courtesy of SoG.

Some people enjoy using family tree computer programs. A comparative table of those available is at www.My-history.co.uk.Many are based on the transferable ‘Gedcom’ format, so once you have typed in your data you can move it between programs, including the one used in Genes Reunited.

Others (like me) aren’t so keen: most have limitations, or pester you for ‘vital data’ that you don’t have, almost forcing you into making misleading assumptions. Many demand dates of birth, marriage and death. From 1855 onwards in Scotland this is all very well, as these are very well recorded. Before then, however, Old Parochial Registers (and most non-Established church registers) can record baptisms, not births, and proclamations, not marriages, and few programs make allowances for such subtleties, resulting in people entering the former as the latter. Just recently I saw a Family Group Sheet giving a death date of 5 July 1617. The evidence was a burial dated 6 July 1617, and my poor client, browbeaten by the computer’s demand for a date of death, had simply guessed that the burial was the day after the death – which is in fact rather unlikely.

Читать дальше