This photograph of Catherine and Jane Wilson in 1923 is usefully marked on the back ‘Drummond Shields Studio, Edinburgh’, thus suggesting the area where these girls may have grown up (courtesy of Jane’s daughter-in-law, Helen Taylor).

When you interview a relative, use a big piece of paper to sketch out a rough family tree as you talk, to keep track of who is who. Structure your questions by asking the person about themselves, then:

• their siblings (brothers and sisters)

• their parents and their siblings

• their grandparents and their siblings

…and so on. Then, ask about any known descendants of the siblings in each generation. The key questions to ask about each relative are:

• full names

• date and place of birth

• date and place of marriage (if applicable)

• occupation(s)

• place(s) of residence

• religious denomination, whether Church of Scotland, Free Church, Catholic, Jewish, and so on.

• any interesting stories and pictures.

Next, ask for addresses of other relatives, contact them and repeat the process. Once you know the name of a village where your ancestors lived, try tracking down branches of the family who remained there, for people who

Before Christianity and literacy came to Britain, a special class of Druid, the seanachaidh or sennachie, memorized and recited the royal sloinneadh or pedigree. Long after other forms of Druidism had fallen away, sennachies remained, some as villagers who remembered the local family histories, others in the clan chiefs’ households. In about 1695, Martin Martin wrote in A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (Birlin, 2002):

‘Before they engaged the enemy in battle, the chief druid harangued the army to excite their courage. He was placed on an eminence, from whence he addressed himself to all of them standing about him, putting them in mind of what great things were performed by the valour of their ancestors…’

Martin, who used the term ‘marischal’ for the chief’s sennachie, also said he was,

‘obliged to be well versed in the pedigree of all the tribes in the isles, and in the Highlands of Scotland; for it was his province to assign every man at table his seat according to his quality; and this was done without one word speaking, only by drawing a score with a white rod which this marischal had in his hand, before the person who was bid by him to sit down; and this was necessary to prevent disorder and contention; and though the marischal might sometimes be mistaken, the master of the family incurred no censure by such an escape.’

It’s good to know that, occasionally, we genealogists were allowed to get it wrong.

Dr Johnson (1709-84), the London essayist and lexicographer who travelled around Scotland with the writer James Boswell in 1773, had trouble finding whether the bard and sennachie were different people, or one and the same, though he acknowledged different customs may have prevailed in different places: touring the Hebrides, he found that neither had existed there for some centuries. However, we do remain: Lord Lyon is High Sennachie of Scotland, and all genealogists worth their salt have inherited their share of this ancient Druidic mantle.

Aristocrats, such as John Campbell, fourth Duke of Argyll, shown in this painting by Thomas Gainsborough, have always had the help of sennachies or genealogists to record their family history.

have never left may know a lot about the ancestors you have in common, and might have tales about your forbears who migrated away.

What you are told will be a mixture of truth, confused truth and the odd white lie. Write it all down and resolve discrepancies using original sources. Watch out for ‘honorary’ relatives. Whilst writing this, I received an email telling me, ‘I recall as a boy, being introduced to people named to me as Uncle Ned, Auntie Jo, and Cousin Francis. Many years later, I found during my family history searches that none of them were in fact relatives, just very close friends at that time. Yet the oldest relative I was interviewing still described them as Uncle, Auntie, and Cousin, even under my challenge, with the result that I spent many weeks searching records for these people as relatives, and I never found any of them – but I eventually did find them as ordinary individuals shown as living in the same neighbourhood.’

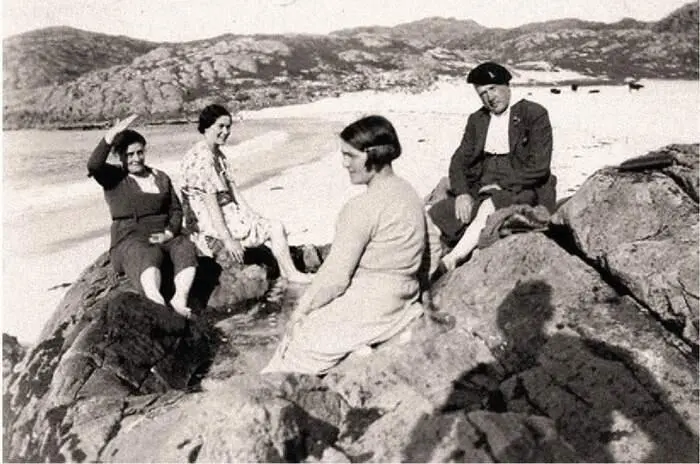

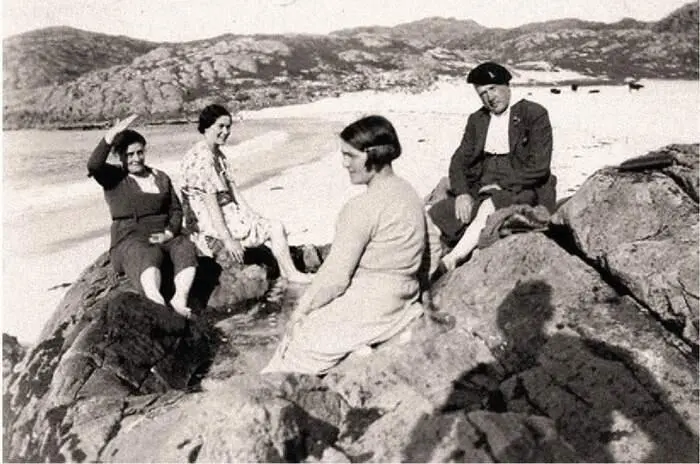

Photographs of family holidays are particularly valuable when people used the time to retrace their roots. Alexandrina (‘Alice’) MacLeod left her ancestral home in Badnaban, Sutherland, to become a servant in Glasgow, marrying Walter Hooks there in 1935. They came back on holiday, bringing along Walter’s parents: here she is with her parents-in-law and sister Annie at nearby Achmelvish. There is more on tracing the roots of this family on pp. 50-1. (Photo courtesy of MacLeod Family Collection.)

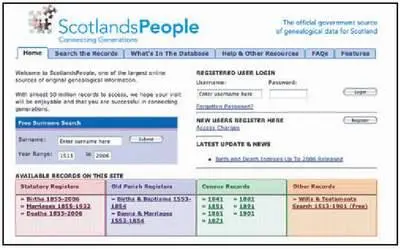

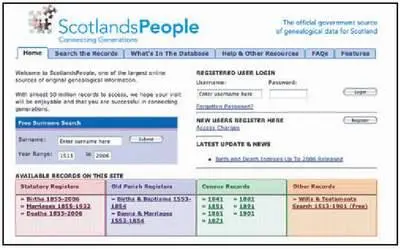

Genealogy has been revolutionized by computers, bringing data and even images of records to your own home and, more significantly, making them really easy to search. Being able to look at the whole Scottish 1851 census online is useful: being able to search it in seconds for your great-granny is revolutionary. Scotland has led the way in making its national records accessible and searchable online, and the website www.ScotlandsPeople.gov.ukis a unique resource that has changed the face of Scottish genealogy for ever. It is your great good fortune to be tracing your Scottish family history now.

Computers are readily available in libraries or internet cafés (or friends’ houses!). If you don’t use the internet already, I would strongly recommend learning from a friend or joining a class, as it will make tracing your Scottish roots vastly easier. If you absolutely can’t bear the idea, ask an internet-savvy friend or relative to do your look-ups for you.

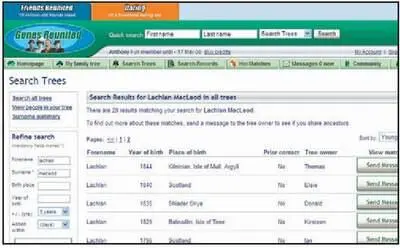

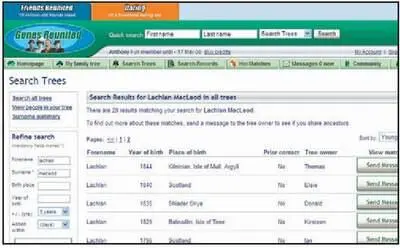

LEFT: A page from www.genesreunited. com showing a list of references to ancestors called Lachlan MacLeod. You can tell which may be relevant by the years and places of birth: by clicking on the name you can send an email to the person who submitted the information.

There are several excellent websites that put like-minded genealogists in touch with each other, particularly the British-based www.genesreunited.com, though sites such as the American www.onegreatfamily.comwill contain many families of Scottish descent too. You enter names, dates and places for your family, and the sites tell you if anyone else has entered the same details. When new people join and enter the same relatives, they’ll easily find you. It’s a new method, that really works.

RIGHT: The front page of the ScotlandsPeople website.

Читать дальше