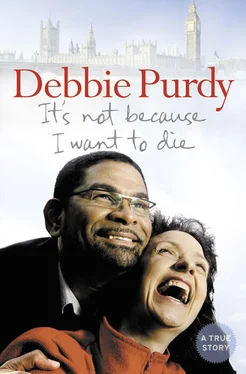

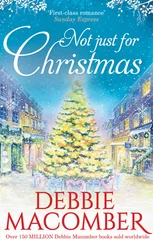

It’s Not Because I want to Die

Debbie Purdy

Cover Page

Title Page It’s Not Because I want to Die Debbie Purdy

Preface

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains

Chapter 2 Wading through Honey

Chapter 3 ‘Can I Scuba-Dive?’

Chapter 4 My Beautiful Career

Chapter 5 The Boys from Cuba

Chapter 6 ‘My Missus’

Chapter 7 ‘Your Grass Is White’

Chapter 8 In Sickness and in Health

Chapter 9 The Baby Question

Chapter 10 The View from 4 Feet

Chapter 11 The Big Four

Chapter 12 Let’s Talk about Death

Chapter 13 The Speeding Train

Chapter 14 Cuban Roots

Chapter 15 A Negotiated Settlement

Chapter 16 A Short Stay in Switzerland

Chapter 17 Entering the Fray

Chapter 18 My High-Tech House

Chapter 19 Some Real-Life, Grown-Up Decisions

Chapter 20 My Day(s) in Court

Chapter 21 Round Two

Chapter 22 The Tide Turns

Chapter 23 My Own Little Bit of History

Chapter 24 Listening to All Sides

Chapter 25 Lucky Me

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the publisher

‘Jump!’ the instructor yelled.

I obeyed instinctively, then immediately regretted it. What the hell was I doing jumping out of a perfectly good aeroplane 3,000 feet in the air?

‘One thousand and one.’ Training kicked in and I adopted the spread-eagle position, face down. Why am I doing this? What was I thinking?

‘One thousand and two,’ I counted aloud, as we’d been taught, then squinted upwards. Was there any way back into the plane? Surely there had to be. I was still attached by a static line that would pull my chute open. Could I climb up it?

‘One thousand and three.’ The Doc Martens I was wearing were too wide and my feet were shaking, hitting each side so rapidly I thought they might come loose and fall off. I can’t believe I’m doing this, I thought. This is so stupid.

Terror was making me alert to every tiny sensation and I could feel the blood pumping hard through my veins.

‘One thousand and four. Check, shit, malfunction. If your parachute hasn’t deployed by the time you’ve finished counting, you’re in trouble and it’s time to open your secondary chute. Just then, though, I felt a gentle lift and I was pulled upright as my main chute opened. The static line detached and I felt intense relief as I looked up at the billowing white canopy. I’ve never felt so grateful to see anything!

The relief was short-lived because I then looked down and saw that there was nothing between me and the ground. I was falling more slowly, but I was still very definitely falling.

It was deathly quiet up there, and very peaceful. I’d been told to scope out a big yellow cross on the ground and aim for that using the toggles on either side of my chute to change direction, but I couldn’t even see the damn cross. Where the hell was it? I spotted a parachute in front of me and thought I would just aim for that in the hope that it was aiming for the cross. All the guys who were jumping with me that day had seemed cool, calm and confident, so I figured that whoever I was following was going the right way.

I played with the toggles but wasn’t sure how much effect I was having. I kept aiming for the guy ahead and praying that he wasn’t headed for a tree. I still couldn’t see the cross, but by that stage I didn’t care if I was miles away so long as I hit the ground with both feet and didn’t end up hanging from an electricity cable or the upper branches of a tree.

Suddenly the ground was right there and I closed my eyes and went into autopilot, rolling on impact as we’d been taught. When I opened my eyes, I looked down my body to make sure nothing was broken or bleeding and realised my arm was lying on a yellow cross. I’d landed right on top of the target. The guy I had been following was a few hundred yards further on. There was no blood. I was alive and intact.

The instructor who filled out my logbook later wrote, ‘GATW,’ meaning ‘Good all the way.’ I didn’t mention that it was a matter of luck rather than careful control. I felt fantastic. Sheer terror turned to sheer exhilaration and I asked, ‘When can I have another go?’

That was in 1981 and I was 17 years old.

In 1995, fourteen years later, a doctor said to me, ‘When I first saw you, I thought you had MS,’ and inside my head I started to count, one thousand and one.

He organised an MRI scan and a lumbar puncture. One thousand and two.

It was MS and I was in freefall, scared and lonely. One thousand and three.

I walked into the arrivals hall at Singapore’s Changi Airport and saw Omar waiting. I felt a gentle lift and I was upright again – still falling, but I knew I was safe and would be able to control my descent.

I haven’t hit the ground yet. What follows is the story of my journey down so far.

Chapter 1 A Heart in Chains

In January 1995, at the age of 31, I had recently moved to Singapore and was earning my keep with a pen. (Well, a Mac laptop, but that’s product placement!) I wrote brochure copy for an adventure travel company, and music reviews and features for a number of magazines. A welcome perk of my job was that I got into all the live music clubs free, so of course I was having fun (especially as the bars wouldn’t take money from me for drinks). I shared a flat with an Australian bass player, Belinda, and a Japanese teacher, Tetsu, and was dating my fair share of men without having anyone serious on the scene.

One night Belinda came home from work raving about a band she had seen playing in a club called Fabrice’s. ‘There are seven gorgeous men,’ she said, ‘and they’re explosive on stage. You have to see them.’

‘What are they called?’

‘The Cuban Boys.’

I rang Music Monthly to ask if they’d be interested in a review and they said, ‘Sure.’

I was interested in exploring why foreign musicians were frequently paid so little. I had dreams of doing some investigative journalism to rival All the President’s Men. It was a genuine problem, but I have to admit I was looking for a problem I could bury myself in solving.

I turned up at Fabrice’s on the afternoon of 25 January, toting my notebook and camera, to sit in on the band’s rehearsals. My first thought was that ‘the Cuban Boys’ was a strange name for a group that had seven blokes and three girls in it. My second thought was that Belinda had been exaggerating. Only two of the band members, Emilio and Juan Carlos, were particularly good-looking, while the rest could be described as having ‘good personalities’.

It was the band leader, Omar Puente, who came over to talk to me for the interview, and I thought he seemed a bit Mafioso with his little moustache. He sat opposite me looking very serious and frowning in concentration as we struggled to overcome the language barrier. I spoke English, some Norwegian and a little French, while Omar spoke Spanish, Russian and a little French, so French it was. It took me about twenty minutes to get a single quotable sentence. (I wasn’t 100 per cent sure of how much I understood, but he didn’t read English, so I was unlikely to be sued.)

I picked up the camera and motioned that I wanted to take a picture of them playing. Omar indicated in sign language that they should get changed into their performance outfits, instead of the casual clothes they were wearing.

‘No, don’t bother,’ I said. ‘If you could just play a number for me as you are, that would be fine.’ I motioned towards the stage.

When they started playing, I was instantly impressed. They had a really good sound, and Omar’s violin-playing was fantastic. The repertoire comprised modern and traditional Cuban dance music, but Omar also did a little Bach as a solo and I could hear humour as well as hard work and technique in his playing. On the violin he obviously felt in control; he was a complete master of it.

Читать дальше