In the middle of the set, the band launched into a version of ‘La Cucaracha’. The percussionist, Juan Carlos, stood on his chair and put one leg on his conga drum. Then they all stopped playing and did pelvic thrusts in time to the ‘Da-da-da-da dah-dah’ bit in the chorus. It was crude and obscene, but mesmerising.

I came back to Fabrice’s later that night to watch the proper show. The band was not dressed up in their performance shirts, so I figured Omar had been trying to be interesting for the press. (Now I realise it was me he was trying to impress.) He had a very charismatic presence, interacting with the audience and chatting to them between numbers, and moving around the stage with ease. He wasn’t the best-looking band member, but you couldn’t take your eyes off him, mainly because you wanted to see what he would do next. All the band members moved with an easy, natural rhythm, the music was note-perfect, and their set was a huge hit with the regulars at Fabrice’s.

After they finished playing, Omar walked off stage and came over to sit beside me, bringing his friend Rolando, who spoke a bit of English and tried to translate for us.

‘Will you be nice about us in your magazine?’ Omar and Rolando asked. Well, that’s what they were trying to ask.

‘Of course,’ I said. They were so earnest and incredibly entertaining to watch that being anything less than glowing about them would have been like kicking a puppy.

The two of them would feverishly converse in Spanish, words tripping over one another, for several minutes before Omar would try to say something in English.

‘Do you live in Singapore?’ he asked next, and I told him that I did.

Our scintillating conversation floundered a bit when one of Rolando’s girlfriends arrived, but Omar didn’t leave my side for the rest of the evening except to get back on stage and play the second set.

At two or three in the morning, when Singapore was winding down, I was in the habit of stopping at a market for an early breakfast on the way home. I invited Omar to join me so we could continue trying to talk. We borrowed an English–Spanish dictionary, as Rolando didn’t consider his role much fun and the girlfriend clearly was. We walked down to the market and bought bowls of congee (a kind of rice porridge) and some other snacks, and sat at a roadside table to eat.

Now we were away from his job and the band, Omar dropped his earlier, more fatherly persona and started to be flirtatious, touching my arm and offering me bites of his food to sample. It dawned on me that he thought I had asked him on a date. I was just being professional and finishing the interview (I think). He was all smiles and charm until he accidentally bit on a piece of chilli, which ruined his composure. His eyes started watering and he was coughing and spluttering. I handed him a bottle of water to cool his mouth down. Not the most romantic start, and nothing to indicate that this would be the love of my life.

I still hadn’t asked about how much the band was being paid, so I opened the dictionary at the word ‘fee’. Omar signalled, ‘Twenty,’ with his fingers.

‘A day?’ I was horrified.

He nodded.

I thought we were talking about Singapore dollars, which

are worth a lot less than US dollars. Believing that the band was being paid a tiny fraction of what their Singaporean counterparts would earn, my trade-unionist instincts kicked in and my hackles rose. After some frantic investigation, though, I realised that he was telling me how much their daily allowance was, rather than their total fee, and he was talking in US dollars.

I later learned that their income had also been affected by a bad business decision. Most musicians pay an agent fee to whoever got them the job. For this type of long-term contract, it’s usually no more than 15 per cent, and if two or more agents are involved they share the fee. Omar had been a band leader for a short time and his business skills were only marginally better than his language ones. Consequently, his limited (to put it politely) English meant that the Cuban Boys were paying two agents 15 per cent each, which resulted in the ten Cubans receiving just 70 per cent of the fee. It didn’t seem right, but no one person was to blame. The band saved most of their pay to buy instruments, as they would need better equipment to be the next ‘super group’. I could see they would also need better business sense.

We had been speaking at cross-purposes and not even in the same language. It’s hard to make sense when you have to flick through a whole dictionary to locate every word, and even when you find the right one, cultural references mean you still speak at cross-purposes.

After I’d finished eating, I stood up to leave, laying my hands against my cheek to indicate that I needed to sleep. Dawn was breaking and people with normal jobs were starting to make their way to work. Omar asked, ‘Fabrice’s?’ and I realised he was inviting me to come to the gig that evening. I couldn’t make it, so I shook my head and said, ‘Au revoir. A bientôt.’ The Singapore music scene was tiny and I had no doubt we would bump into each other again before too long.

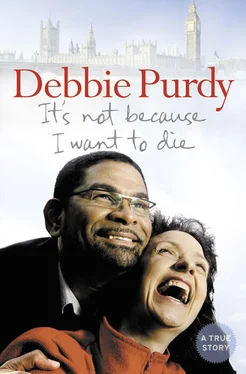

Years later we would still disagree on the details of the day we met. I remember wearing a little black dress, looking sexy and sophisticated, whereas he said I was wearing a white T-shirt and a black skirt. (I know he’s wrong because he says I wasn’t wearing a bra!) I probably had the skirt and T-shirt on in the afternoon for the interview (but with a bra) and the dress on in the evening when I returned to the club for the set. He says it was me who came on to him, whereas I know it was definitely him. He says he was initially attracted by my bottom, and even said so in an Observer article in 1998. (Talking about the size of a girl’s bottom in print must be grounds for divorce!) I wasn’t really that interested in him at first, but I loved the way he played violin. We had the same experience, but we both have different memories of it. Mine, of course, are right!

A couple of days after meeting Omar, Belinda and I went to a jam session at Harry’s Bar – all the musicians in Singapore ended up there on Sundays because if you played you got free drinks – and as soon as we walked in I spotted Omar. He came straight over, but there was an awkward silence because there wasn’t much we could say without someone to translate for us. Normally, you would move on and talk to someone else at this point, but Omar sat down. We listened to the music and had a few drinks. Every time a male friend of mine came over to chat, Omar positioned himself between me and the other man like a bodyguard and watched intently. I wasn’t sure that I wanted this sort of attention, but I felt flattered to be pursued by someone so ‘present’. Gradually I realised that he seemed to have decided I was his.

Back at the flat I shared with Tetsu and Belinda, Belinda quizzed me about him. ‘He looks pretty interested. How about you?’

‘A moot point – we can’t even discuss the weather. He seems nice, but he could be an axe murderer for all I know.’

Belinda couldn’t communicate with him either, and his easy charm and macho display at Harry’s rang warning bells. Besides, her own experience of Latin musicians hardly endeared Omar to her. She herself knew charming Latin men who would quickly make beautiful declarations of love, mean it when they said it, but then leave the room and fall in love with someone else, before finally going home to a wife and kids.

Omar was only a year and a bit older than me – 33 when we met – but he took responsibility for the whole band, and being a band leader is probably the closest thing to being a parent you can get without having to change nappies. Omar could never relax properly at Fabrice’s, where he had nine Cuban kids to look out for. The language barrier was the main problem for them all, but there was always something ready to trip them up. They had a safe refuge on stage. When the band members were together, they could be themselves – crazy and funny, a little wild but always in control – and they had their fearless leader, who was, like any parent, ready to do anything to protect them. Omar loved his band, his music and his life. There was no language barrier with a violin in Omar’s hands.

Читать дальше