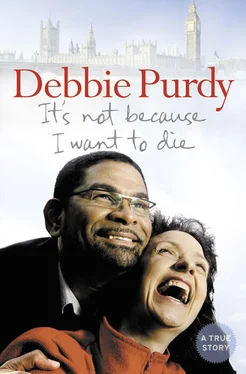

‘Debbie, the only thing I can tell you is that it’s not going to get any better. That’s pretty much it.’ He was watching me closely for a reaction, but I was too busy weighing up his words and trying to read causes for optimism into them. ‘Get on with everything you want to do whenever you want to do it, and when you find you can’t do something, just stop.’

‘OK,’ I said cautiously.

‘Meanwhile I think we should measure you for a walking stick to help broaden your base.’

What? My base is broad enough as it is, thank you. (Like I said, my bottom just can’t be disguised, but people don’t have to comment!)

The neurologist obviously saw my confused expression. ‘I mean to steady your walking,’ he replied, smiling. ‘You’re dragging your left foot a bit.’

My walking was particularly wobbly because I’d sprained my ankle navigating some uneven ground with Mildred’s partner just before I left Singapore. We’d gone out walking in a quest for fitness and had ended up having to take a taxi home after my stumble. The episode seemed ridiculous now.

‘OK,’ I said. I hadn’t realised you needed to be measured for walking sticks, but apparently you did.

‘Any more questions?’ he asked, leaning back to indicate he had all day if I needed, even though I knew he had a bulging waiting room outside.

So I took a deep breath and asked the Big One: ‘There’s no cure, is there?’

‘No, there’s no cure.’

We sat in silence for a while, my mind blank. I knew there were dozens of questions I should be asking, but I couldn’t think of them and the list I’d made lay forgotten in my pocket. I decided I had better let him get on with his day, so I stood up, shook his hand and turned to leave.

I was halfway through the door when I turned back.

‘Can I scuba-dive?’ I asked, thinking about my job on the adventure travel brochures.

‘I don’t know. Can you?’ he replied.

It took me a few more days to process and digest all the information he had given me because it was just so contrary to what I’d expected. I’d had a good life and thought of myself as a lucky person. Suddenly things were running away from me, escalating out of my control. I’d been expecting to be diagnosed with something serious but curable, not some incurable illness that would just keep plodding on relentlessly. I wanted something glamorous with bells and whistles. I wanted miracle-drugs and dramatic surgical interventions and cutting-edge medical breakthroughs.

‘This is it, the end of my life,’ I sobbed to my sister Carolyn. ‘It’s going to get worse and worse and then I’ll die.’

‘Stop being so histrionic,’ she told me. ‘The doctor might have got it wrong. Even if he’s right, there’s bound to be something that can be done. We’ll just find out what it is and we’ll do it.’

Although they’re very different personalities, all my siblings reacted in much the same way. My brother, Stephen, was typically matter-of-fact: ‘Right, OK, let’s get on with things, then. No point making a fuss.’

The neurologist had said it was incurable. How was that possible? If my dad were still alive, I knew he would have found a cure. He’d been an incredible character. Thrown out of school at the age of 13 because he had a tendency to question the ‘correctness’ of his textbooks rather than spouting the answers teachers wanted to hear, he made a career out of his questioning mind. He was working as a photo-journalist for the Brighton News Agency when he was asked to look after a friend’s typesetting business while he was on holiday. Dad thought there had to be a better way of setting type rather than placing each letter by hand. Other people had tried, but they hadn’t been able to create the right size or shape of cathode-ray tube (the things that make televisions work). Dad didn’t have any qualifications in electronics, and he hadn’t read the books that would have told him that it wasn’t possible to manufacture a tube of the size he wanted, so he just went ahead and made the right size of tube and used it to build the Linotron 505, which was the first commercially viable cathode-ray-tube typesetting machine.

He’d always been creative. Back at the age of 13, just before he was thrown out of school, he thought of a way of improving the mechanism of wind-up gramophones and wrote to HMV to tell them about it. He got a letter by return saying they had already done it, but they were impressed by his initiative and invited him to work for them. Sadly, he had to decline on the grounds that he was just a schoolboy.

Dad had tremendous enthusiasm for a challenge, as I have, and would work on one project for a few years and take it as far as he could before moving on to the next thing. After some years working as a photo-journalist, photographer and icecream maker, he found his raison d’être in new technologies that helped to revolutionise printing. The word ‘incurable’ would never have been in his vocabulary. Like Augusto and Michaela Odone, who researched and formulated a new drug called Lorenzo’s Oil after their son, Lorenzo, was diagnosed with ALD (adrenoleukodystrophy, to give it its full name), my dad would have taken my MS diagnosis as a challenge. I’m convinced he would have cured me because he could make most things possible.

If Mum were still around, she would have given me a big hug and said, ‘Don’t worry, Debbie. We’ll get through this, whatever it takes.’ She was gone, though, and I had no one left to give me a mother’s unconditional love.

This thought made me cry more than any other. I had to face this on my own, without parents. If my dad had still been alive, I’d have gone to stay with him in America and let him take care of me. I’d have felt more secure if I had even just one parent to fall back on. My sisters and brother were sympathetic, but they had busy lives with jobs and partners, and I didn’t want to move in with them and lie on a sofa waiting for things to get worse. I had to figure out how to manage this disease on my own.

Should I stay in the UK to be near my doctors? Should I go back out to Singapore and try to carry on with life as it had been before? That seemed to be what the doctor was suggesting, but I was scared I wouldn’t be able to manage on my own out there if my symptoms worsened.

And what about Omar? We’d only been dating for two weeks before I came back to the UK for my appointments. He couldn’t be expected to take my problems on board. I didn’t even know how I could begin to explain them to him, given the language barrier. He would still be in Jakarta, but I had a phone number for the club there, so I decided to call and attempt to explain what had happened.

First of all, I rang the Spanish Embassy in London and asked the woman who answered the phone, ‘How do you say “multiple sclerosis” in Spanish?’

‘Esclerosis múltiple,’ she told me. (So glad I got that sorted!)

Then I rang Omar and tried to tell him, in our usual mishmash of languages, what was wrong.

‘Je suis malade. Esclerosis múltiple.’

I was crying and I hadn’t a clue what he was saying or even whether he had understood, but the calmness of his tone was comforting.

‘No te preocupes. Come back to Singapore.’

‘OK,’ I sniffed. I’d had a look at the flights and there was a cheap one available on 3 April, so I told him I would get that.

‘See you at Fabrice’s!’ I said, hoping he would pick up on the name and understand what I meant.

When I walked through the arrivals gate at Changi Airport expecting to be met by my boss, Peter, there was Omar standing waiting for me. I’ve never been so pleased to see anyone in my life. I ran into his arms and hugged him tightly, so relieved I couldn’t speak. It was a wonderful, euphoric feeling. But what was he doing there? How had he known which flight I was on? I hadn’t mentioned it to Mildred and he didn’t know Peter.

Читать дальше