|

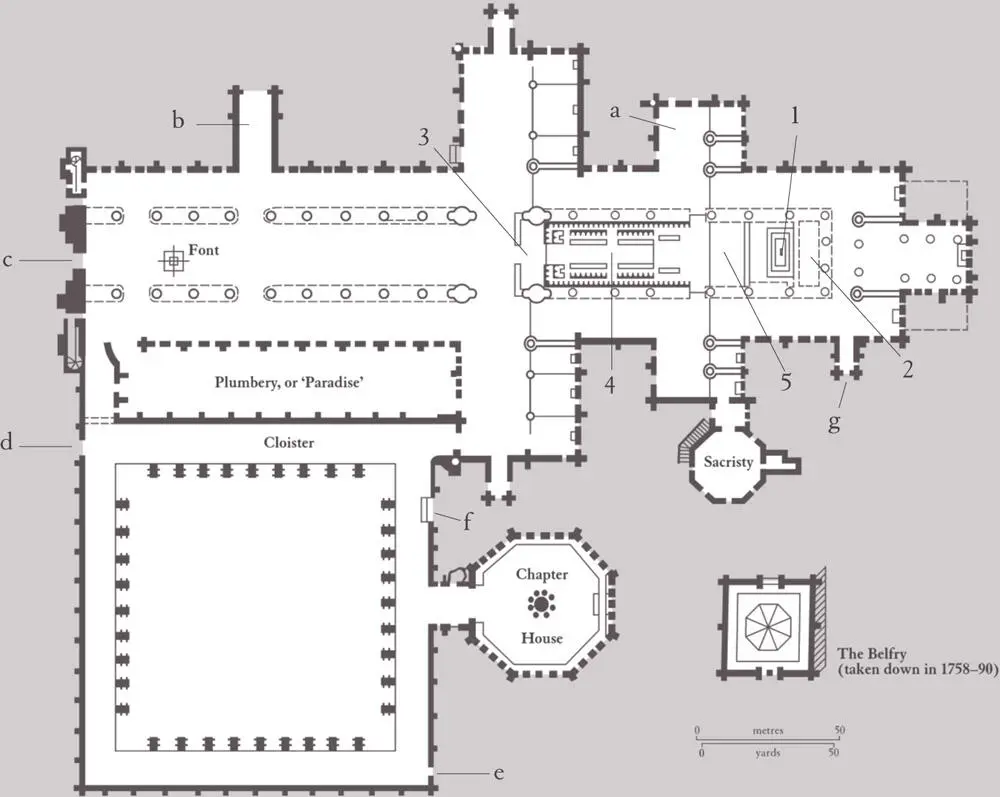

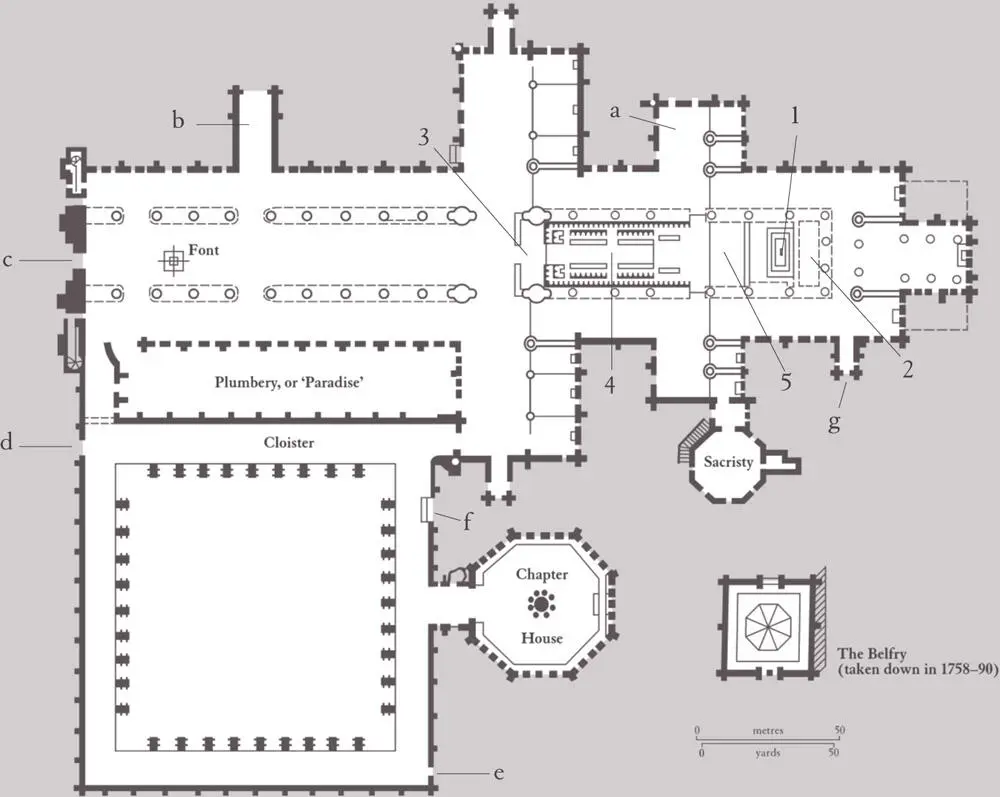

| Fig. 108 Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire; plan of the cathedral showing liturgical arrangements. Liturgical features: 1) high altar; 2) Shrine of St Osmund; 3) pulpitum with rood above; 4) choir stalls; 5) presbytery. Doors: a) original entrance; b) entrance for laity; c) west entrance reserved for processional use; d) exit to cloisters for processional use; e) exit to Bishop’s palace; f) exit to cemetery g) exit for funerals. |

| These spaces were available to the laity, when not in use by the canons and monks, and strategically placed boxes would elicit donations from the curious and the pious. The cathedral’s shrines would be regularly visited and at some times of the year mobbed. Pilgrims would leave objects at the shrine as either offerings of thanks or as requests; in 1307 papal commissioners listed 2,204 items next to St Thomas’s shrine at Canterbury, including nightgowns, ships made of wax, wood and even of silver. On ordinary days people would congregate in the seat-less naves and genuflect at the Elevation of the Host. But many would come for the spectacle of the processions and for the music, both of which would have been infinitely more impressive than any parish church could achieve. 25 |

| New Urban Religious Institutions |

| Growing towns, filled with increasingly well-off and literate populations, began to present a challenge to the Church in the late 12th century. Its structures were organised to minister to populations in rural areas, where congregations were illiterate and priests barely above the intellectual level of their rustic parishioners. The rectors of churches in towns had either been appropriated by monasteries or were too poor to attract educated clergy. The church thus perceived a crisis in which educated townspeople would fall into heresy uninformed by the teachings and guidance of the Church. The solution was a radical new type of monasticism, that of the mendicant friars. The friars broke with the established principles of monasticism by refusing to own property and relying on charity for support, while at the same time abandoning the seclusion of the cloister to work among ordinary citizens. In 1221 the first of these orders, the Dominicans (Black Friars), came to England, followed in 1224 by the Franciscans (Grey Friars). 26 |

| By 1250 the two orders had established 70 convents in England, and 100 by 1300. Friaries of both sorts were found in 30 towns and, as other orders such as the Carmelites (White Friars) and Austin Friars joined them, many towns might have as many as four friaries. These were often built on the peripheries, as most of the central plots were already occupied by the mid 13th century. The new orders became very fashionable and almost immediately enjoyed generous patronage from bishops, the universities and, crucially, the Crown. Edward I, for instance, never visited a town without giving alms to the friars. As the friars were not allowed to own property their buildings were held in trust for them by corporations of citizens. Individual donors gave buildings or plots of land, but friars never held estates for investment like earlier orders. |

| At first friaries were very modest, even deliberately uncomfortable, but as their congregations grew the friars needed places in which to preach and work. The earliest surviving Dominican house is at Gloucester. Here there were also Grey and White Friars, but the first were the Black Friars, invited to found a house in 1239. Although later converted into a domestic house, here the essential features of an urban friary can be grasped. The church has a very wide nave designed to enable men from the town to hear sermons. The chancel is much narrower and was for the friars themselves, 40 in all. The rest of the buildings accorded to no set plan, as each friary organised its ancillary buildings itself. At Gloucester there was a simple cloister of timber and, on the south, its most important and rare survival, a library or scriptorium. This has ten or more carrels on each long side, divided by stubby stone screens and each lit by its own window. |

| The friars, like their predecessors, eventually acquired property and became rich, profiting from the desire of wealthy town dwellers to speed the passage of their souls through purgatory. The richest friaries, such as the London Blackfriars, which enjoyed consistent royal patronage, became palaces with luxurious lodgings and guest accommodation, as well as big, handsome churches. 27Much of the Norwich Blackfriars survived the Reformation as a civic building and, even in its current state, gives a strong impression of a large and luxurious foundation ( fig. 109). As with the friary at Gloucester the space inside the church was maximised, with narrow aisles and a wide nave lit by big windows and a slight clerestory. The junction between the nave and the chancel was occupied by an octagonal tower, a common feature of urban friaries. The passage beneath it gave access to the cloister, chapter house, dormitory and refectory. In due course the design of parish churches was influenced by rich and fashionable urban friaries such as Norwich; in addition, after 1350 they too began to have wide naves lit by big windows. Friaries were one aspect of increasingly sophisticated urban institutions stimulated by money and population growth. Another was the development of a new type of hospital. Burgesses in rapidly growing towns became ever more concerned about the underclass and people without family support who were too old, sick, disabled or deranged to work. Institutions were founded to support these people, combining charitable aims with a rigorous liturgical regime. Some were built, as earlier hospitals had been, by bishops or the aristocracy, but many were founded by the corporate efforts of rich townsmen. Most were sited on the outskirts of towns, partly to exclude the sick from the centre and to provide for the incoming wayfarer, but also because it was believed that the stress and noise of town centres discouraged recovery. 28 |

|

| Fig. 109 Norwich, Blackfriars, now known as St Andrew’s Hall. The only complete surviving friars’ church in England, it dates from 1440–70 – a rebuilding of the original foundation of 1307 after a fire. Yet the layout is entirely 14th-century. |

| Bishop Walter Suffield of Norwich founded the Hospital of St Giles just outside the precincts of his palace in 1245, and by the end of the century it was richly endowed with nearby rural estates, as well as a portfolio of urban properties. In 1270 it absorbed the nearby parish church of St Helen, adding parochial duties to its responsibilities. Its prime purpose was to care for the sick and aged priests of Norwich, but it also cared for a minimum of 30 others and fed – and in the winter, warmed – 13 others each day. Four sisters assisted by four lay brothers cared for the sick, while the master and four chaplains saw to their spiritual needs and prayed for the soul of the founder. 29St Giles’s Hospital was large and well endowed, one of the reasons for its survival to this day (p. 175). Many others were not. Hospitals that tended to the needs of wayfarers, especially pilgrims, were often overwhelmed and under-funded. The roads of medieval England were brimming with the ill, the disabled and the mentally disturbed making their way to nearby shrines, or sometimes on long pilgrimages in search of healing. Monasteries and other great houses had a duty of hospitality, but small hospitals played their part, too. |

| Life of the Rich and Powerful |

| The 13th century was a good time to be an English landed magnate. Throughout the century incomes rose and landlords had increasing disposable wealth. Six earls had an income of more than £3,000 a year and two of them grossed more than £6,000; at least half a dozen were on £400 to £3,000 a year and most barons earned between £200 and £500. To put these figures in context, a good annual wage for a labourer was £2 and the peacetime revenues of the Crown were only £30,000 a year. So there were a lot of rich people and in total their disposable income was probably in the region of £500,000 a year, more than ten times the income of the entire state. These people invested in building to a greater or lesser degree. Building maintenance probably absorbed about 5 per cent of a magnate’s annual resources and there were also almost always capital investments, such as for barns and mills. In addition, a significant proportion of their disposable income was spent on new domestic architecture, in some cases up to 25 per cent. 30 |

| The general increase in the wealth and architectural capability of landlords contributed to social changes that were already underway. Communal feasting and hospitality remained at the heart of medieval life, and lords found ways of making their halls even larger and more spectacular. At the same time they increasingly wanted to spend time in more intimate spaces and withdrew from their halls to chambers in which they could spend time with their families and peers. This led to important changes in the design of high-status houses that become apparent from the 1180s. 31 |

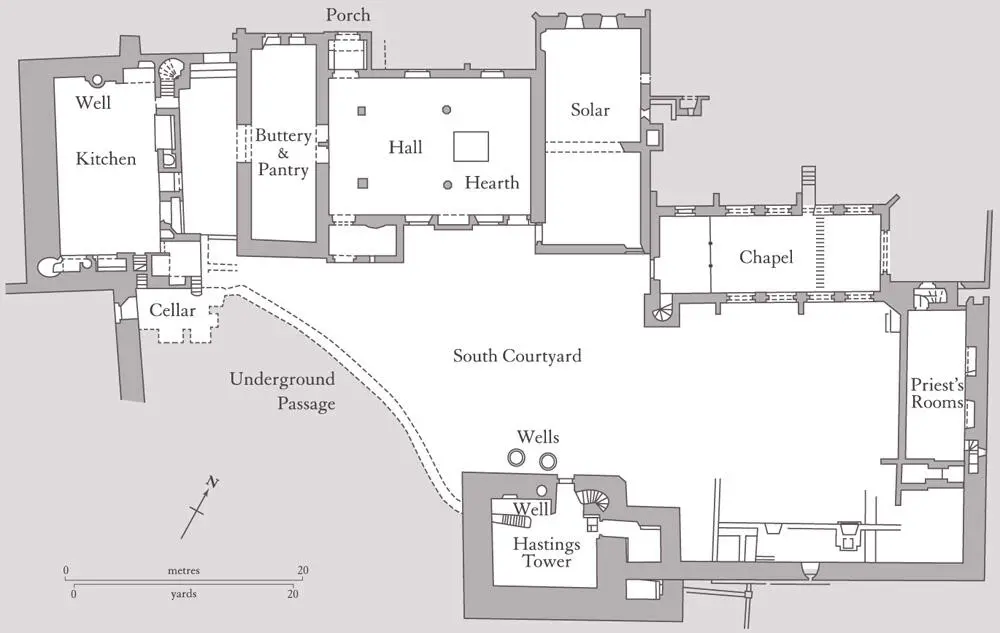

| Up until the late 12th century the houses of the rich were generally an agglomeration of separate structures: hall, chamber and kitchen. But from the 1180s houses began to adopt a new arrangement that was to become the standard layout for all houses of pretension for the following 400 years. Essentially what happened was that kitchens began to be built on to one end of the great hall, forming a single unit; then, from the 1220s, chamber blocks were also constructed integrally with the great hall but at the other end from the kitchen. This gave the great hall an ‘upper’ end adjacent to the lord’s private rooms and a ‘lower’ end adjacent to the kitchens. Whilst the hall was generally still on the ground floor the chambers at the upper end were stacked above it, so a stair led up from the lord’s end of the hall to his rooms above. The kitchen, also on the ground floor, often had guest chambers above it, and a secondary stair would have led to these ( fig. 110). |

Access to the great hall was no longer from a door in the centre of one of its long walls but through a door at the lower end; this door led to a passage that was screened off from the rest of the hall by a timber partition. Doors from the kitchen, from the buttery (for beer) and pantry (for bread) would lead into this enclosure, which became known as the screens passage. This more integrated arrangement allowed lords to spend more time in the comfort of their chambers while coming and going through their halls. This private space was a badge of rank, part of the charisma of greatness and wealth. To be inaccessible was to be important, as it enabled favour to be shown and intimacy to be conferred and withdrawn. More exclusive rooms that often included private chapels (or oratories) were further symbols of exclusivity. 32