Cover

Title Page

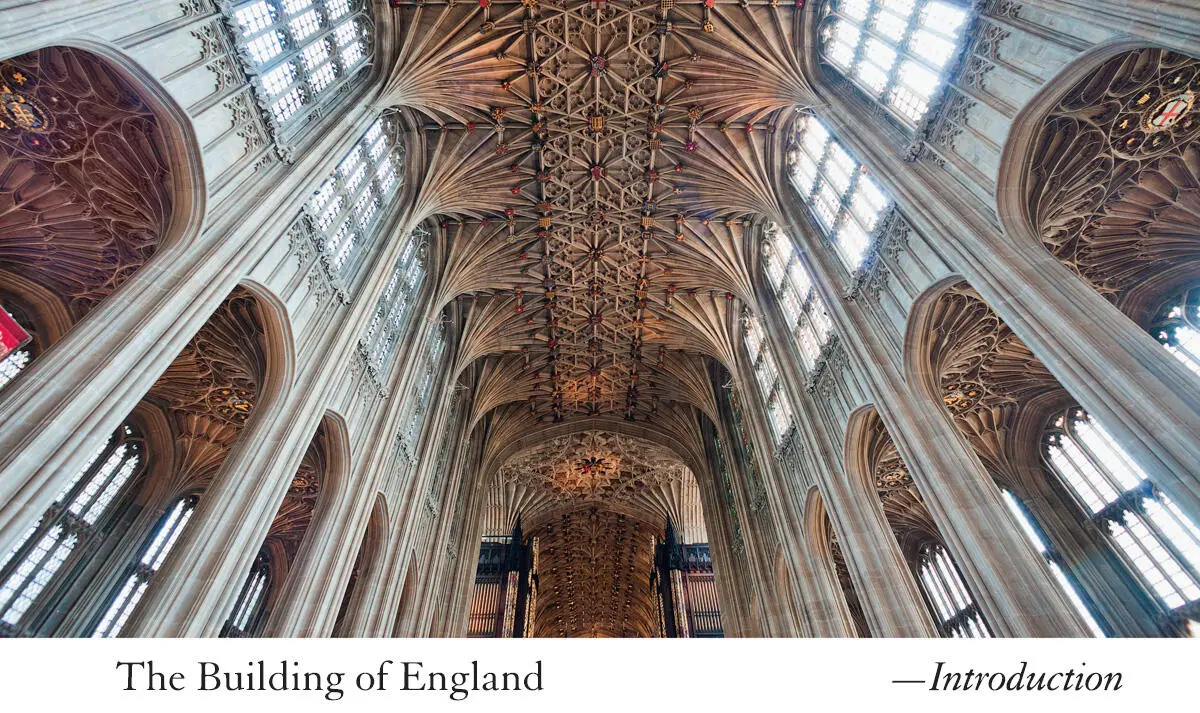

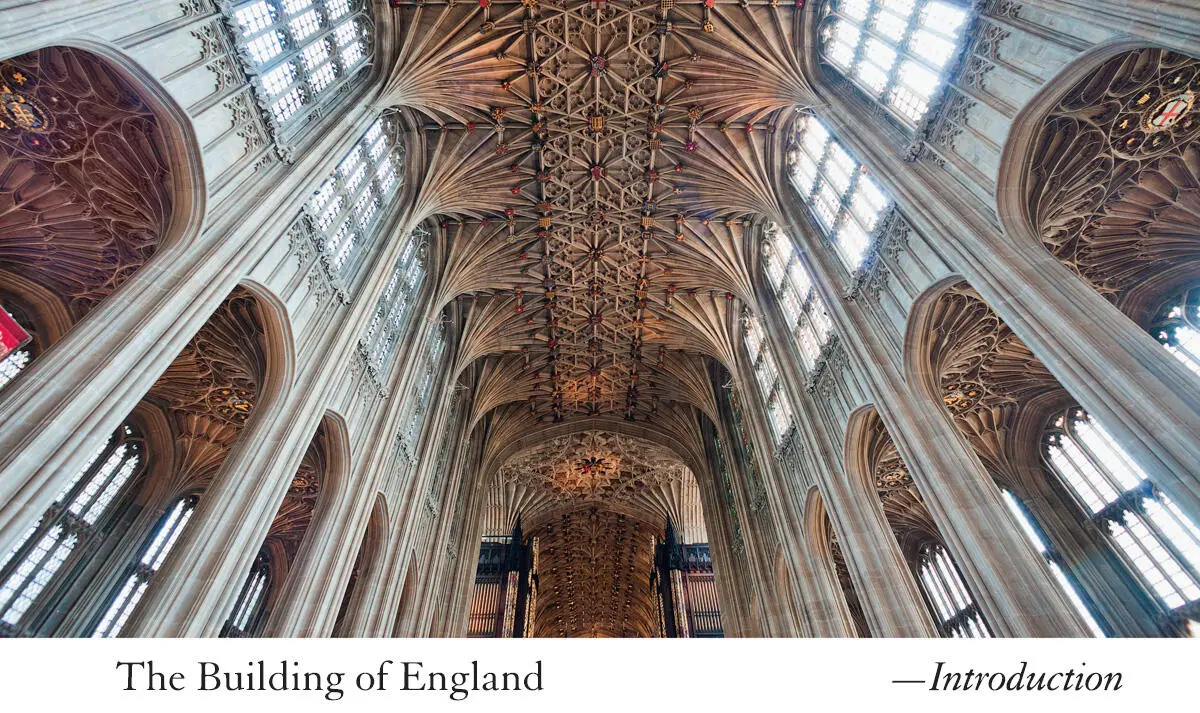

Introduction

1— Beginnings: The Collapse of Rome: 410–700 Splendid is this masonry – the fates destroyed it; the strong buildings crashed, the work of giants moulders away. The roofs have fallen, the towers are in ruins, the barred gate is broken.

2 — The Foundations of England: 700–1000

3 — England and Europe: 1000–1130

4 — The Invention of English Architecture: 1130–1250

5 — Extravaganza: 1250–1350

6 — From the Black Death to the Reformation: 1350–1530

7 — From the Reformation to the Civil War: A Century of Growth: 1530–1630

8 — Protestantism, Power and Prosperity: 1630–1720

9 — Property, Commerce and Consensus: 1720–1760

10 — War, Inventions and Introspection: 1760–1830

11 — World Dominance: 1830–1870

12 — 1870s to the Second World War: 1870–1939

Endnotes

Picture credits

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Building in England 410–1930

This book is a history of English buildings, although it is intended to be more than that. It is also about the beliefs, ideas and aspirations of the people who commissioned them, built them, lived in them and saw them while going about their daily business. It is about how people discovered new ways of building, both for improved structural performance and for enhanced aesthetic effect. It is about how buildings reflected changing economic circumstances, shifting tastes and fashions. It is about the architectural expression of power, of hierarchy, of influence. It is the history of a nation through what it built.

So this book aims to put building back into the history of England. For some this will be a questionable enterprise because much recent British history is written as the history of the British Isles. 1Yet we should remember Britain was only created by an Act of Parliament in 1707, although the Crowns of England and Scotland had been united in 1603 and Wales had been incorporated in 1536. Thus, for 1,300 of the 1,520 years that this book spans, England and Scotland, at least, were separate political entities. Although now one country, before 1603 England and Scotland generally looked in different directions – and influences on building in each were markedly distinct. Even after the Act of Union, to take a single example, urban housing in Scotland was based on the tenement and in England on the terrace. 2

Moreover, through the whole period covered by this book it was rarely if ever only England that was governed from London. If we are to take a wider perspective on the political and cultural context of English history it would be desirable not only to include Scotland, Wales and Ireland but also to include much of France, the Netherlands, Hanover and, latterly, a huge, worldwide empire. All these places brought influences to bear on English building but it is what happened in England that is the focus of this book.

Writing only about England, the danger is of claiming English exceptionalism. Exceptionalism – the assertion that England was and is fundamentally different from other countries – is a strong streak in English historical writing but will not find much of a place in these pages. Whilst I will argue, repeatedly, that English buildings looked different from those in other countries, this makes no stronger claim than suggesting that buildings in Spain, for instance, looked different, too. Perhaps England was, at certain times, more insular than some other countries, but it was always open to external ideas and influences. There is one period, however, in which I will argue for exceptionalism. After 1815 England moved into a position of world dominance that has had no parallel in history. The achievement was unquestionably a British one, but it was one directed from London. For a period that lasted from perhaps the 1830s to the 1920s England was home to building types and categories of places that were to have worldwide influence. This was exceptional and this book will make no apology for that.

St Pancras Station, London. The engine shed of 1866–8 by W. H. Barlow and R. M. Ordish. With a clear span of 240ft and a length of 690ft this was an unprecedented enterprise.

The Problem of English Architecture

Writing a history of English building is fraught with problems, many of which have been inadvertently caused by architectural historians. Architectural history is still too often divorced from mainstream historical research and, with some notable exceptions, has concentrated either on general popular accounts or on a series of questions interesting only to a small circle of people concerned with stylistic analysis.

This latter approach ultimately derives from the work of the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, who became Professor of Art History at Berlin University and then at Munich in the first decades of the 20th century. His achievement was to establish a more empirical way of judging art and architecture, and his Principles of Art History set out how each artist’s personal style existed both within a national style and a period style. The job of the art historian, he suggested, was to disentangle and explain these stylistic strata. From this time onwards the identification of personal, national and period styles in architecture – and naming them – has been among the primary activities of architectural historians. With most types of buildings thus categorised, architectural history turned in on itself, spending half a century arguing whether the stylistic categories were correct and whether various architects had been allotted to the most appropriate category. 3

My late friend Giles Worsley, writing in his excellent book Classical Architecture in Britain , opens a chapter with two questions: ‘Was Sir William Chambers a neo-Classical architect? Was Robert Adam a neo-Palladian architect? Convention,’ he writes, ‘would give a positive answer to the first question and a negative one to the second.’ 4This present book does not set out to address such questions. The problem, as I see it, is that almost every art-historical term has ended up being more of a subject for debate than what it attempts to describe. So, for instance, there is much disagreement about whether ‘Norman architecture’ or ‘Palladian architecture’ can really be said to exist. 5

A closely related problem concerns the assumptions that flow from the identification of a particular style. After deciding when a style begins – an art-historical industry in itself – historians see it growing, maturing and then waning. This view of style has both Darwinian and moralistic overtones. But styles do not have a life cycle and so there is nothing particularly degenerate, late or waning about late Gothic architecture, any more than there is anything immature about early Gothic. Nor is there any reason to assume that things evolve from the simple to the complex or from the small to the large.

These ideas about stylistic development lead to a series of assumptions that have distorted much writing on English architecture. At its root is the problem of determinism; in other words, the temptation to tell the story of English building as if everything that happened was inevitably going to bring about the outcome we see. There are many examples that illustrate this, but here I present just two. The first concerns the search for the origins of the more faithful rendition of classical buildings seen increasingly in England after 1720 and commonly called Palladianism. Knowing how the story ends, historians have given huge weight to a small number of classically correct buildings built by Inigo Jones nearly a hundred years earlier. As a result, everything that was built between 1630 and 1720 is seen in the light of Jones’s work. Compared with Jones’s buildings, nearly a century of English architecture has been regarded as somehow backward or at least not living up to a standard set by him. The reality is different. Jones’s buildings, at the time, were regarded as oddities outside the mainstream and had little impact on building in his lifetime. He did have his day as an influential architect, but only a century after he was dead. 6

Читать дальше