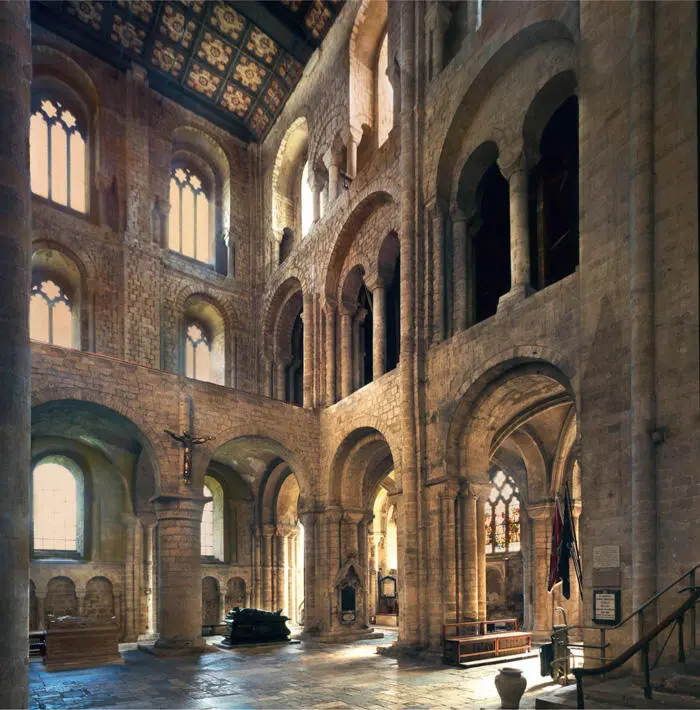

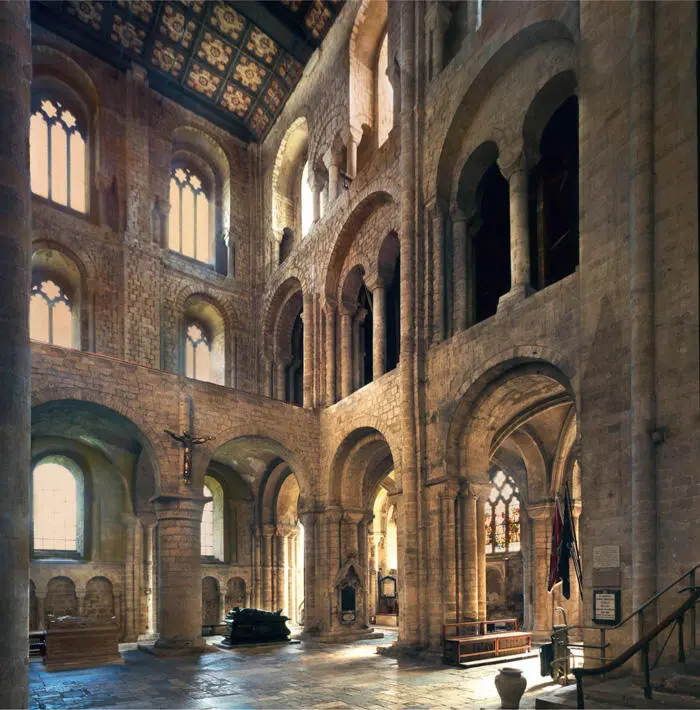

So it is not surprising that in 1070, when the Saxon Bishop of Winchester, Stigand, was deposed, the new bishop, Walkelin, resolved to rebuild the cathedral, emphasising the importance of the city and its royal associations. 16Foundations were laid in 1079, and by the time it was finished it was the largest cathedral in Europe, its dimensions almost identical to those of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome ( fig. 43). The church was cruciform, with transepts as wide as the nave. There were towers at the west end, on the corners of the transepts and over the crossing. Today only the transepts survive from Walkelin’s time ( fig. 44), but here the essentials of the style of the new cathedral can be appreciated. Like the Confessor’s Westminster Abbey, the elevations are three storeys high: a main ground-floor arcade, a gallery above and, crowning that, a clerestory. These levels are tied together by mast-like shafts that rise to the roof. Within this the individual parts of the elevation are subordinated to the whole. The arches at gallery level, for instance, are contained within a larger arch and the whole bay is bounded by piers running from floor to ceiling. The conglomeration of shafts, which visually fragment the piers, disguises the fact that they are, in fact, huge, thick sections of wall supporting the galleries and clerestory above.

The period after the Conquest saw a huge shift in wealth from secular hands to the Church, a shift in landownership not equalled again until the reverse took place under King Henry VIII. Thus Norman landowners such as Robert and Beatrice, the landlords of Asheldham, Essex, endowed their church of St Lawrence by transferring its patronage to a local priory at Horkesley with sixty acres of land. Many such gifts were stimulated by the penitential ordinance of Easter 1067, which set out the penances owed by William’s men who had killed and maimed on English battlefields. Those who were unclear how many English they had slain had a choice: they could either do penance one day a week for life or endow a church. If you were rich the choice was easy. 17

This lent additional momentum to the rebuilding of timber churches in stone that had started around 1000 (p. 68). At Asheldham the timber church was replaced, the main street diverted and a burial ground formed. Asheldham church has now been rebuilt, but a small number of churches rebuilt soon after the Conquest have been preserved largely unaltered because of later depopulation. Such churches vividly capture the everyday experience of worship in the years immediately after the Conquest.

Fig. 43 Winchester Cathedral, plan at tribune (first floor) level. The cathedral, begun in 1079, had many affinities with its Saxon forebears: there were altars in the galleries and a tribune or royal pew at the west end. Spiral stairs led up to the gallery at several points. + indicates a side altar.

Fig. 44 Winchester Cathedral; the north transept. This precious surviving unaltered part of the cathedral shows the raw simplicity and power, almost crudeness, of the early Norman cathedral.

Fig. 45 St Margaret’s, Hales, Norfolk. This lovely church has a Saxon round tower that was heightened in the 15th century, but its nave and apsidal chancel date from the early 12th century.

Fig. 46 St Botolph’s, Hardham, West Sussex. The wall paintings here, done in 1120–30, were covered up in the 13th century and only re-discovered in 1866.

Most of these are two-roomed (or, more correctly, two-celled), with rectangular naves separated from the chancel by an arch. Most chancels originally had an apse but almost all were later rebuilt square-ended. In east Norfolk a couple of remote churches still retain their original apse, and perhaps the best among these is St Margaret’s, Hales. The round tower is later, but the apsidal chancel dates from before 1130 and retains some of its blank arcading ( fig. 45). 18Another group of well-preserved churches is in West Sussex. St James’s, Selham, could be Anglo-Saxon; its masonry and carving are clearly by Anglo-Saxon hands, although the likelihood is that it was built just before 1100. St Botolph’s, Hardham, miraculously retains its wall paintings of about 1120 that were whitewashed over and only rediscovered in 1866. The murals, painted in ochre and yellow, a typical Anglo-Norman bacon-and-egg palette, show St George slaying the dragon (the earliest such image in Britain), and wonderful figures of Adam and Eve ( fig. 46). The halos are painted in green paint made by coating copper plates in urine and sealing them in a container for two weeks. 19

Although these small Norman churches are sometimes almost indistinguishable from their Saxon predecessors, the difference was the discipline that the Normans sought to bring to parish life. Lanfranc’s reforms subdivided dioceses into archdeaconries and deaneries to give greater supervision to individual parish priests. This was important, as most priests before 1000 were in minsters under close supervision; with the proliferation of local churches there were now hundreds of remote priests, poor, ill-educated (often illiterate), undisciplined and isolated. Some were drunkards, some said Mass armed, others had secular employment and many had wives. Almost all were English. Under the new regime more was demanded of them and greater discipline enforced. The life of the average clergyman was transformed in the century after 1066. 20

The impact of the Norman Conquest on English towns was enormous, physically, economically and socially. Saxon lords who had lost their country estates lost their urban lands (burgages) too. In the place of English burgesses Norman landlords settled, and in the place of English town houses new castles, cathedrals and priories rose. Many of these, such as those at York and Winchester, were instigated by royal command; others were the random and illegal acts of new landlords. Norwich was already one of the largest towns in England in 1066 and was to become even more important when the see was transferred there from Thetford. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 almost half of the Anglo-Saxon town had been cannibalised for the Norman castle, cathedral and new housing. One hundred and thirteen houses were demolished for the site of the castle alone, and 32 English burgesses – bankrupted by the seizure of property and royal tax – fled the town. 21

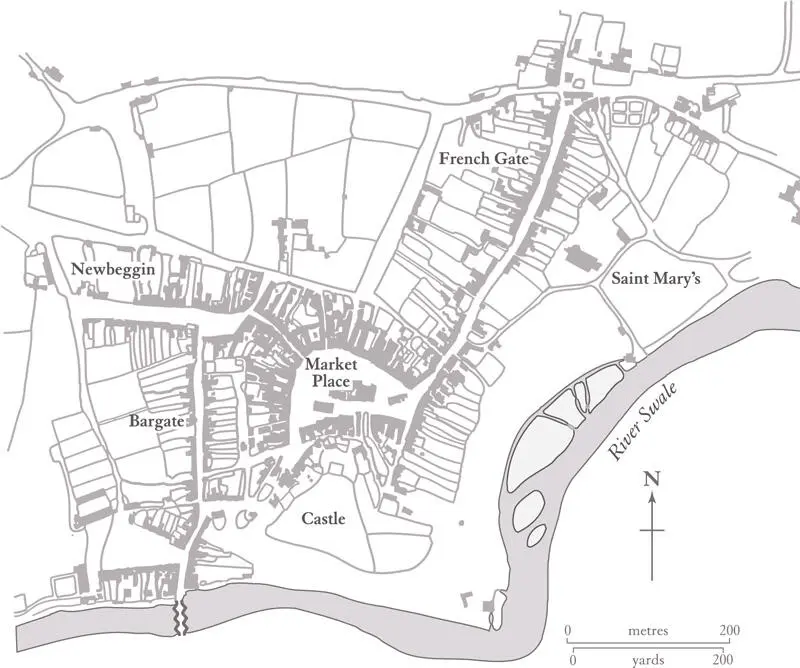

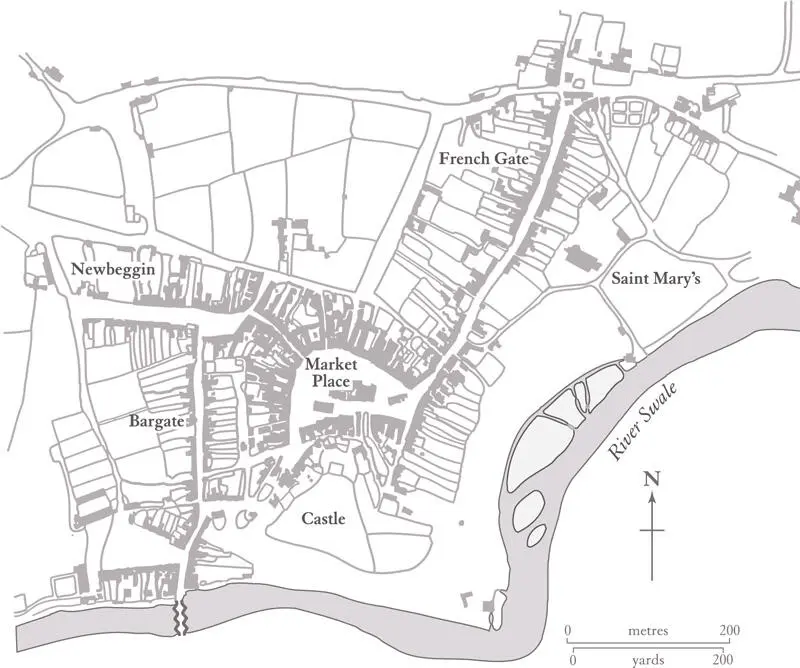

As castles and cathedrals rose, existing towns were re-planned. At Richmond, Yorkshire, a vast castle covering 2 ½ acres was grafted on to a small, pre-existing settlement. Against the castle gate was laid out the market place, and on to this, in a D shape, the burgage plots of the townsmen ( fig. 47). There is no doubt that Richmond was founded on the top of a cliff for military reasons, but the town was designed as an economic engine for Alan Rufus, who began the castle in 1070. Richmond was at the centre of a huge network of arable estates and soon became not only the principal market but also an industrial centre. 22

Fig. 47 Richmond, Yorkshire: plan of the town based on a map of 1773. There are two centres to this town, the original village core round St Mary’s Church on the east side and the semicircular castle borough to its west. Though the castle is perched on a dramatic cliff falling to the river Swale, the reasons for its location were as much economic as military.

Читать дальше