Two buildings started by William, however, were – the White Tower, London, and its sister in Colchester. These colossal structures were palaces for the duke-made-king. They contained a suite of reception rooms and a large chapel in an overwhelming stone-built tower. Such towers had been built for rulers before in the Loire valley and, indeed, in Normandy itself, but not quite on this scale or to this level of sophistication. In fact, scale was integral to their purpose; the parapets of the White Tower were raised far above its roof line to create a more domineering silhouette ( fig. 37). The population of London, as the largest and most important city, and that of Colchester, guarding the east flank of England from troublesome Scandinavia, would be in no doubt that their new king was a mighty and determined master. Yet these were sophisticated residences, too. They had fireplaces with chimneys, garderobes (latrines) and simple, bold architectural settings for thrones, tables and chairs. Furnished with rich textiles, brightly painted wooden furniture and sparkling with candlelit gold plate, these palatial towers were intended to be a pleasure to live in as well as a mighty image of royal power. The White Tower ranks as one of the most important buildings in English architectural history. Its direct influence was to be felt in the design of castles for more than a century and its effects on London continued for more than half a millennium. 12

Great Churches: The First Phase

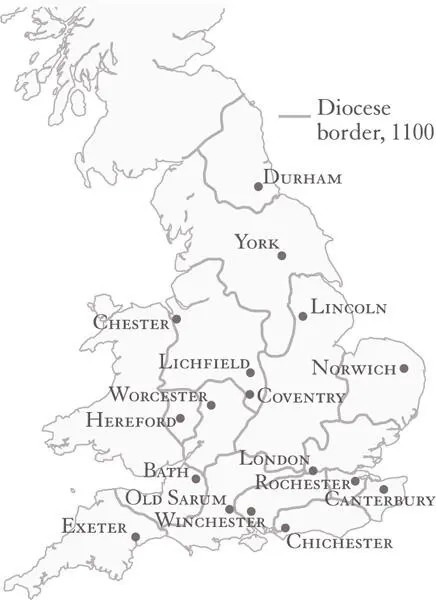

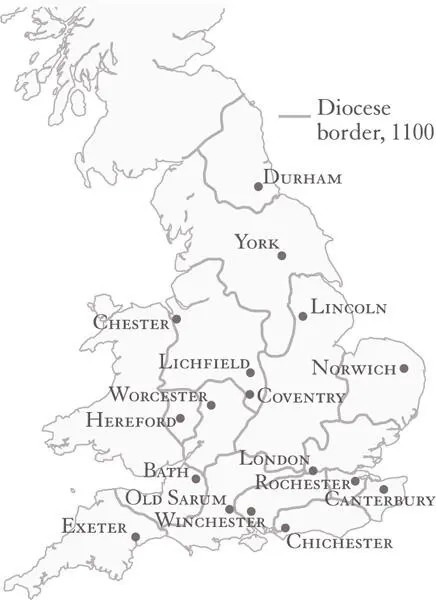

In England and Normandy of the 11th century there was no hard distinction between Church and state. While the pope kept an eye on doctrine, lay rulers effectively governed their national Churches. Both William and Edward the Confessor were interested in Church welfare and reform, and welcomed a series of reforming decrees starting in 1049 that slowly transformed canon law and liturgy in Western Europe. William had promoted reform in Normandy from about 1050 through his chief religious advisor, the Italian abbot Lanfranc, one of the greatest intellectuals of his day, and when William sailed from Normandy in 1066 he did so under the banner of the pope. Once in England, William used his power of appointment and patronage ruthlessly. He appointed Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070 and, in a series of councils between 1072 and 1076, the structure, governance and morals of the English Church were reformed. 13This was as much a political as a moral crusade; with William’s support Lanfranc reorganised the boundaries of Saxon dioceses, moving cathedrals from the countryside to towns and ensuring that the diocese became, like the county, a unit of government control. So the Saxon cathedral at Dorchester-on-Thames moved to Lincoln, Selsey to Chichester and Elmham to Norwich, via Thetford. By the reign of Henry I there were 17 dioceses, with boundaries that remained nearly unchanged until the Reformation ( fig. 41).

Fig. 41 English dioceses in 1100; several, such as Lincoln and York, were huge compared to their modern size.

Within a period of less than 50 years each of these dioceses was to have an entirely new cathedral, perhaps the largest and most ambitious programme in English architectural history. It is easy to imagine that this meant the invention of a new type and shape of church, but there was no simple change from ‘Saxon’ cathedrals to ‘Norman’ ones. The sixteen cathedrals built between around 1070 and 1130 were not identikit structures; each mixed stylistic and liturgical influences in its own way according to the preferences of its bishop, the resources available and local traditions. This had probably not been Lanfranc’s intention. He had hoped to abolish Anglo-Saxon forms and traditions, and bring the liturgical and architectural life of English cathedrals into line with the most advanced thinking on the continent. In this, Canterbury was to be the model. Lanfranc’s Canterbury Cathedral was the most derivative of all the great churches built after the Conquest. Lanfranc had been the abbot of St Etienne at Caen and had overseen the reconstruction of the abbey church there; his cathedral at Canterbury was closely modelled on his old church, right down to the precise dimensions of the transepts and nave. But this was not just an architectural importation. The archbishop set down the liturgical practices he wanted performed in his new country: the Decreta Lanfranci was to replace the Saxon Regularis Concordia (pp 44–5) as the liturgical rule book for the English Church. In composing this, Lanfranc, who had trained as a lawyer and taught logical disputation (dialectic), turned away from the showy, flowery customs of the Saxons and set out a more austere, simpler and more disciplined liturgy. Lanfranc did not have the authority to impose this on everyone, but soon at least 15 monastic houses followed his rules.

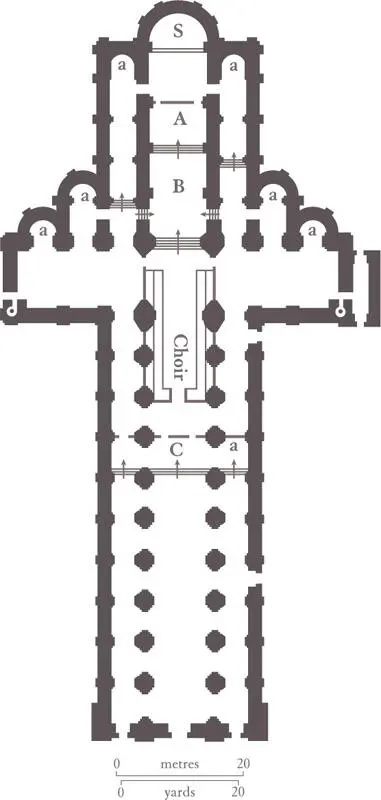

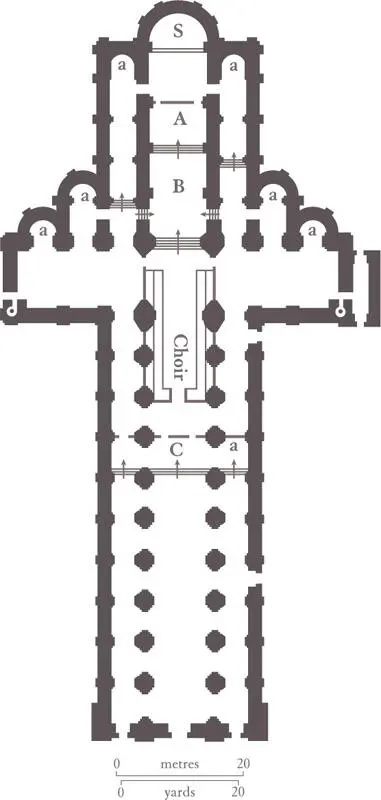

Other than a few fragments, Lanfranc’s cathedral at Canterbury has been completely rebuilt, but remarkably the liturgical arrangements implemented by him can still be appreciated by visiting the abbey church at St Albans, Hertfordshire, which was started in 1077 ( fig. 42). Here there are three liturgical foci: the high altar at the east end; a choir altar for lay people facing the nave; and a huge crucifix (or rood) over the pulpitum (the screen that divided the choir from the nave). At St Albans, as at Lanfranc’s Canterbury, relics remained hugely important and, just as in Saxon churches, the organisation of large numbers of pilgrims had a major impact on the design. The most important relics were either in a crypt below the east end where pilgrims would not interfere with the daily round of monastic services, or, as at St Albans, east of the high altar in a screened enclosure. This definitively divided the church into the part for the monks (the screened-off choir) and the parts for the laity (the nave for services, the shrine at the east end for pilgrims). 14

Whilst a minority of churches followed the liturgical arrangements of Canterbury, most had a more sympathetic attitude to Saxon customs. Several new cathedrals preserved the idea of the westwork, providing a secondary focus at the west end. The most spectacular of these was at Lincoln, where the west end was a massy, semi-fortified bishop’s hall, echoing a Roman triumphal arch ( fig. 38). At Ely, too, a great central tower and part of a western transept survives. We know that at Winchester there was a western structure, now lost. These same cathedrals, like Saxon ones, had extensive areas of first-floor liturgical space for processions and altars. It was possible to do an entire circuit in the broad first-floor galleries at Winchester, and its upper altars were approached by spiral stairs just as in Saxon churches ( fig. 43). 15

Fig. 42 Abbey Church of St Alban, St Albans, Hertfordshire, reconstructed plan showing liturgical arrangements in around 1100: a) side altar; b) relic repository; A) high altar; B) matutinal altar; C) rood altar; S) shrine.

At Winchester one can still gain a good impression of what the interior of the first generation of post-Conquest cathedrals looked like. In the 11th century there was no such thing as a capital city; Norman kings governed as they moved around the country. Yet Winchester, as the seat of the kings of Wessex, had a claim to be the traditional seat of the English monarchy (p. 48). William seems to have acknowledged Winchester’s special status; he rebuilt the royal palace and constructed a castle. He was crowned at Winchester, too, for a second time, by two cardinals and a papal legate, and later his son Rufus was buried there. William also had a permanent treasury at Winchester, and at Easter time the cathedral was the location for one of the thrice-yearly royal crown wearings.

Читать дальше