William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Fergal Keane 2017

Cover image shows the Clonmult IRA unit, reproduced courtesy of Cork City and County Archives

Fergal Keane asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

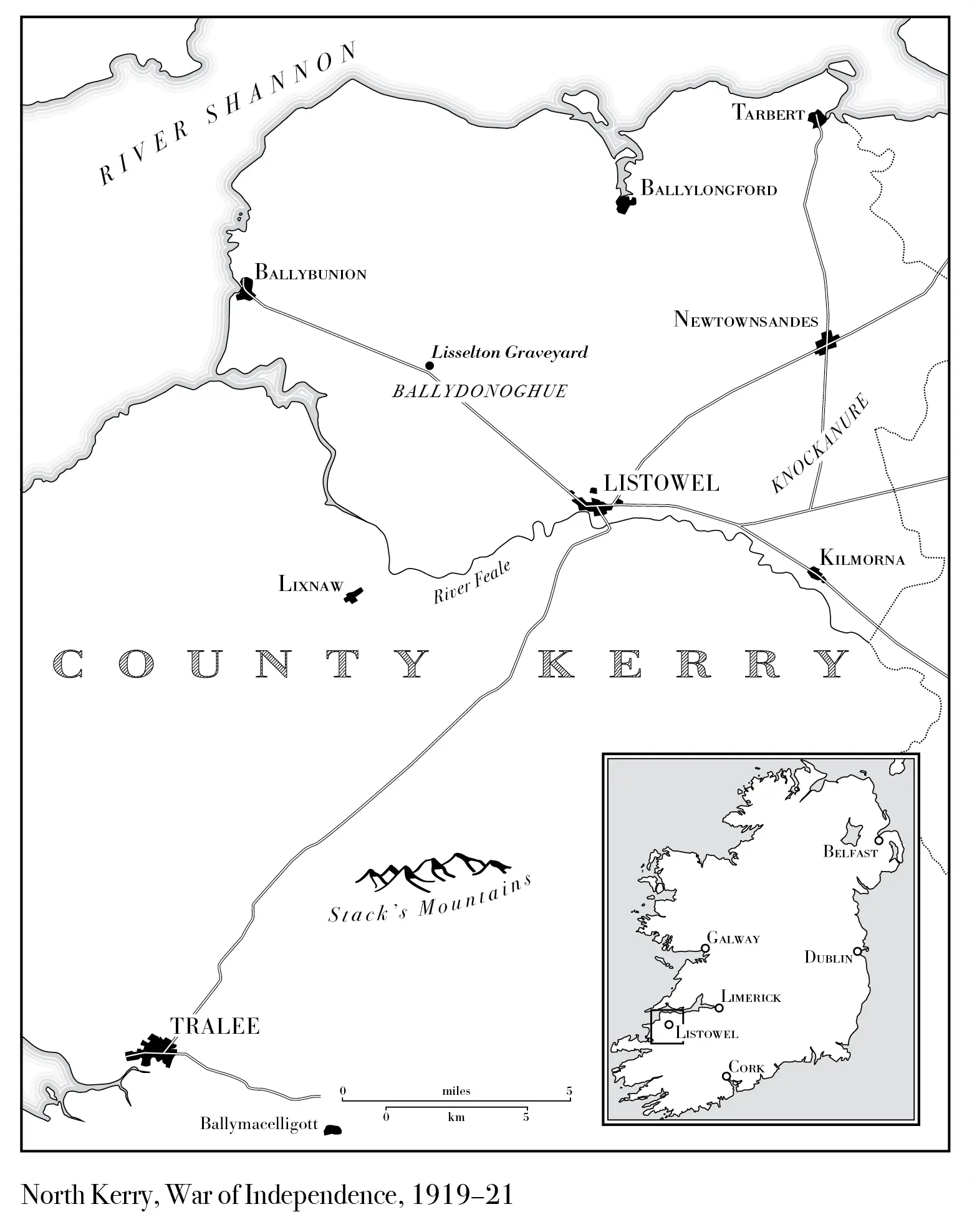

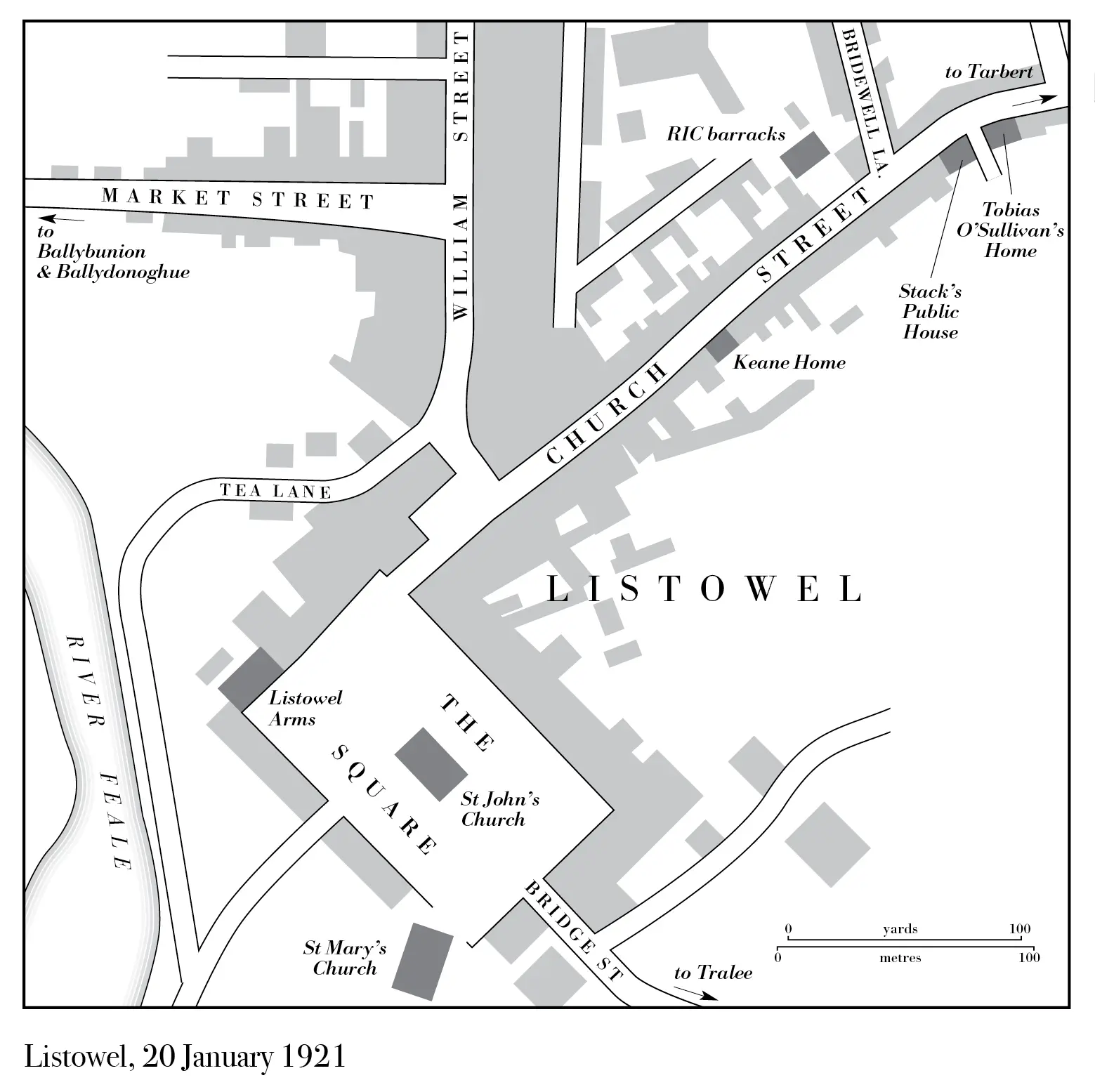

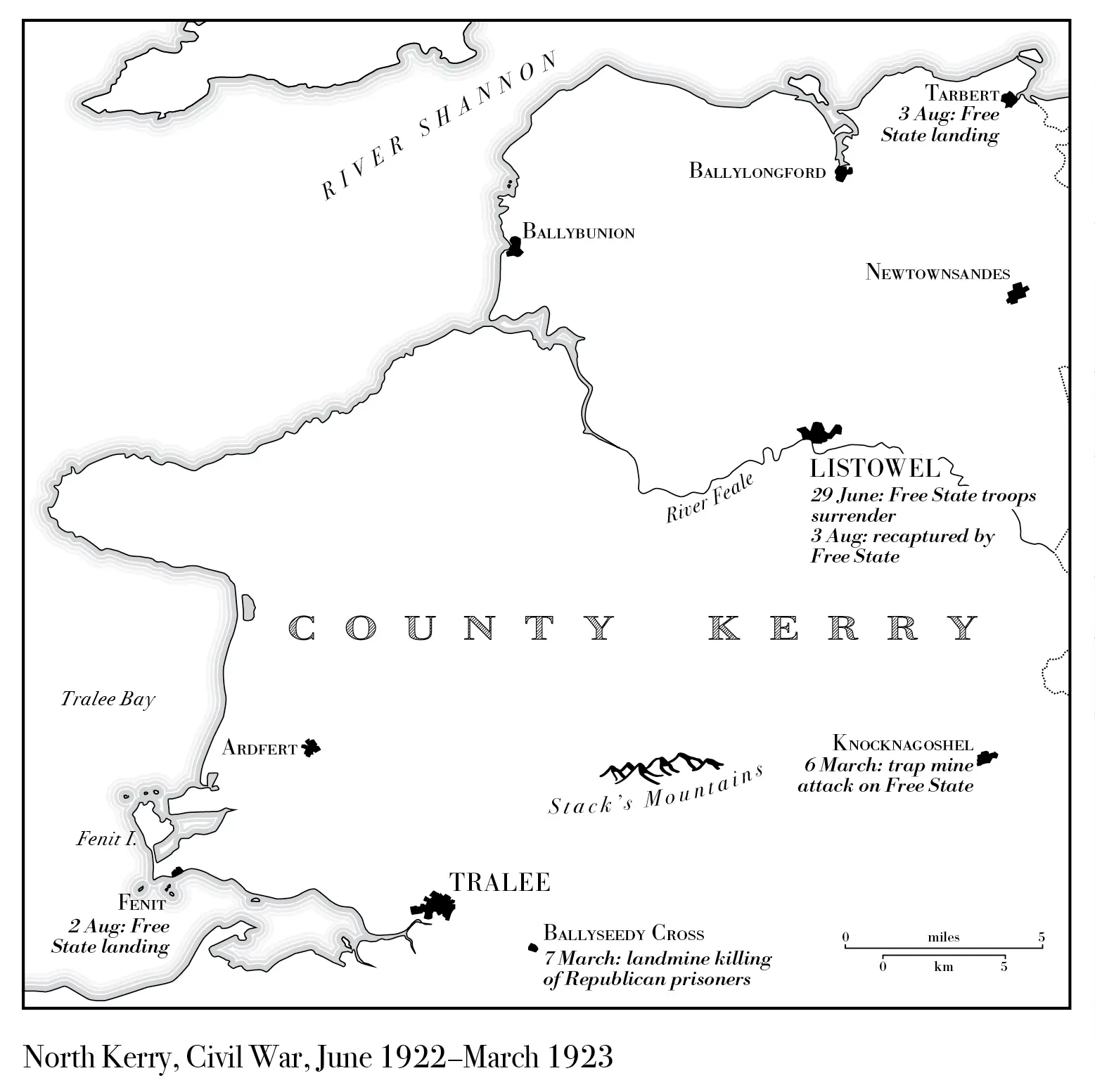

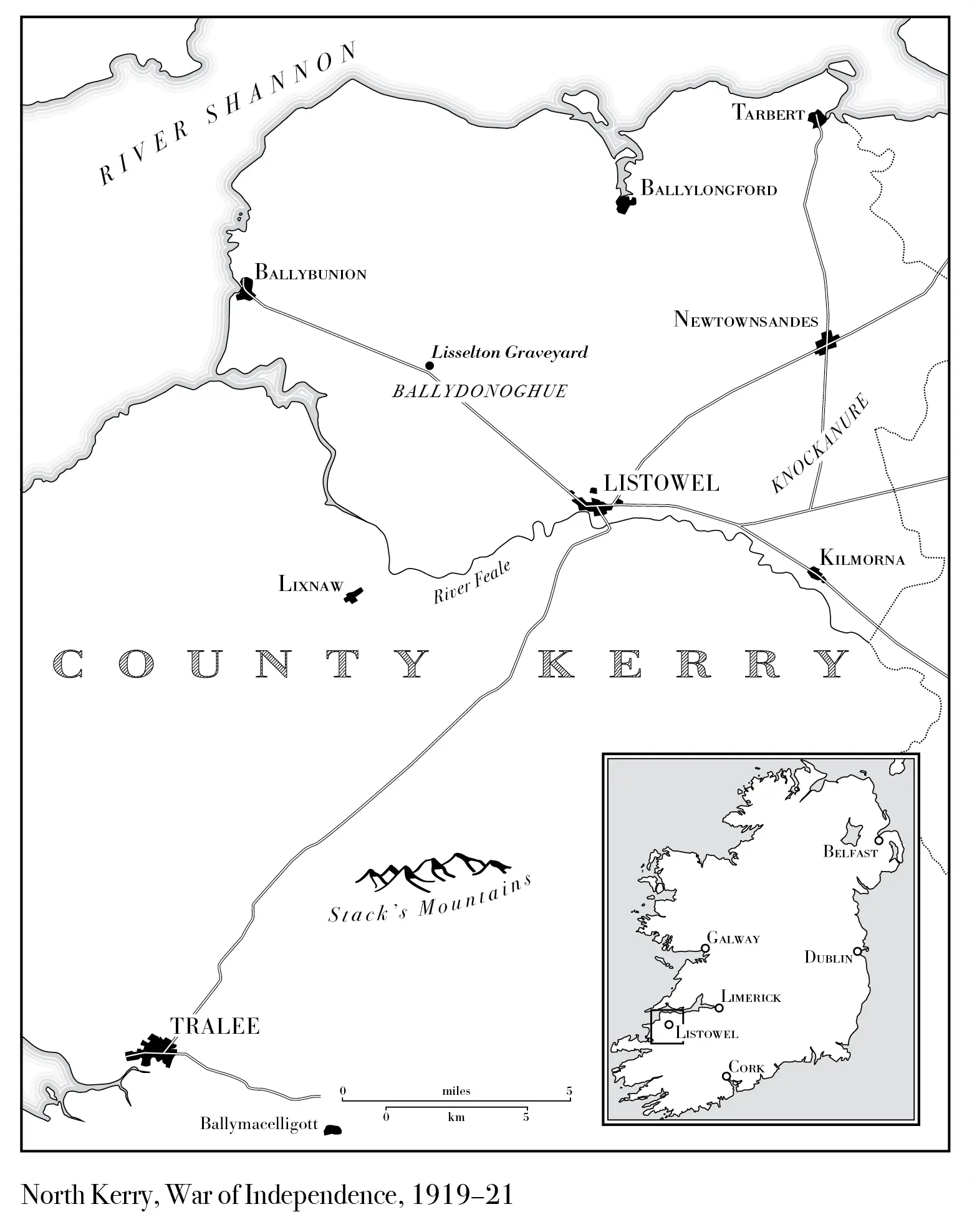

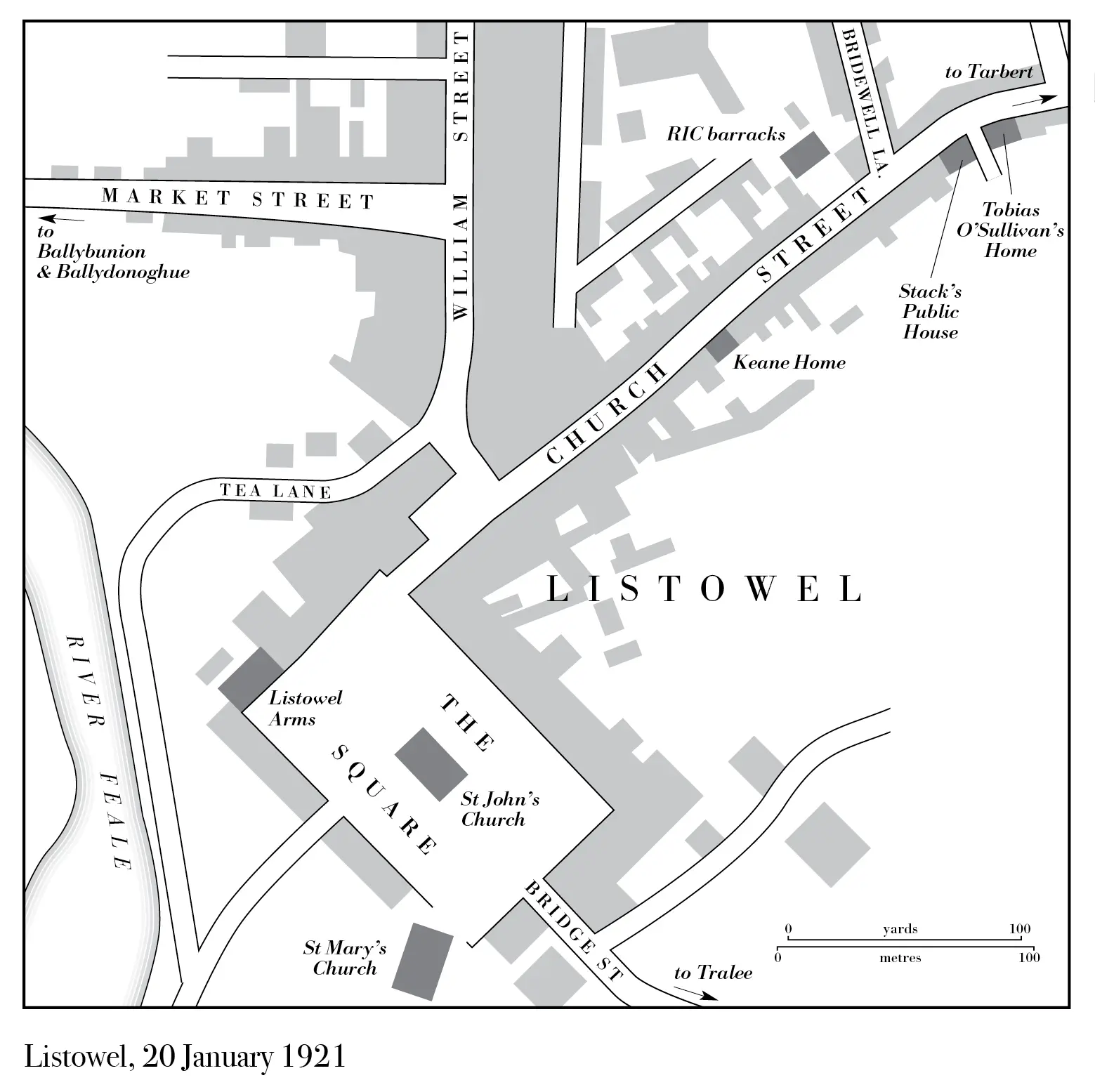

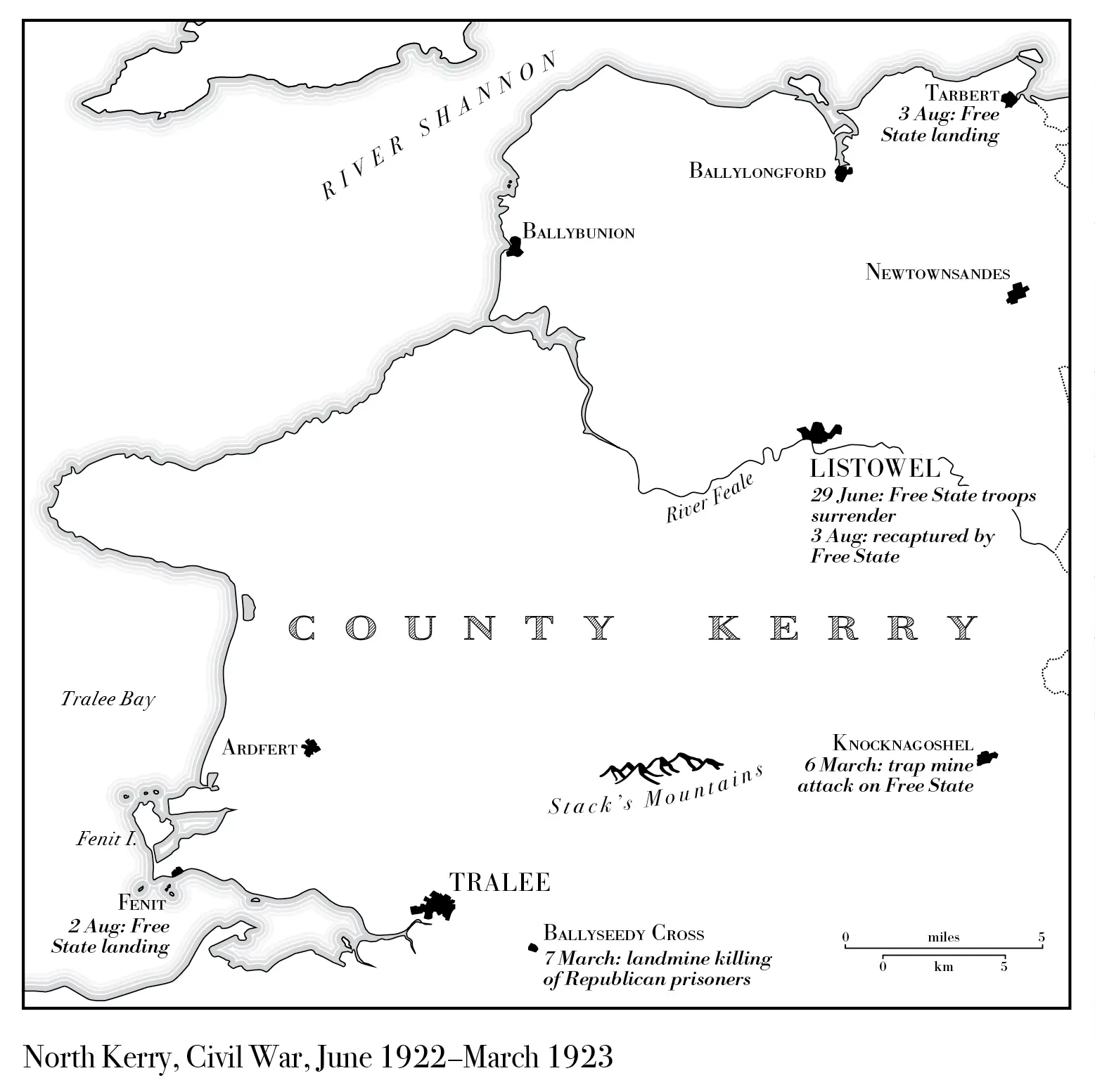

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008189273

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780008189266

Version: 2018-07-30

For Dan and Holly, children of peace

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Prologue: We Killed All Mankind

1. The Night Sweats with Terror

2. The Ground Beneath Their Feet

3. My Dark Fathers

4. Revolution

5. Tans

6. The Abode of Wolves

7. Sunshine Elsewhere

8. Assassins

9. Between Gutter and Cart

10. Executions

11. The Republic Bold

12. The War of the Brothers

13. A New Ireland

14. Inheritance

15. Afterwards

Acknowledgements

A Short Note on Sources

Notes

Chronology of Major Events

Glossary

Select Bibliography

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

His manner was that the heads of all those (of what sort so ever they were) which were killed in the day, should be cut off from their bodies, and brought to the place where he encamped at night: and should there be laid on the ground, by each side of the way leading into his own tent: so that none could come into his tent for any cause, but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads … and yet did it bring great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk, and friends lie on the ground before their faces, as they came to speak with the said Colonel.

Thomas Churchyard, A Generall Rehearsall of Warres , 1579

I

This is the story of my grandmother Hannah Purtill, who was a rebel, and her brother Mick and his friend Con Brosnan, and how they took up guns to fight the British Empire and create an independent Ireland. And it is the story of another Irishman, Tobias O’Sullivan, who fought against them because he believed it was his duty to uphold the law of his country. It is the story too of the breaking of bonds and of civil war and of how the wounds of the past shaped the island on which I grew up. Many thousands of people took part in the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed. The story of my own family is one that might differ in some details but is shared by numerous other Irish families. They may have taken different sides but all were changed in some way, and lived in a new state defined by the costs of violence. I have spent much of my life trying to understand why people will kill for a cause and how the act of killing reverberates through the generations. This book is, in part, an attempt to understand my own obsession with war.

It starts in my grandmother’s house in the north Kerry town of Listowel, in the middle of the 1960s.

The house is asleep. My brother and sister are in beds at the other side of the room. My mother is in the room across the landing, next to the door leading up into the attic where cracked uncle Dan once lived among the cobwebs and the crows. The last drinkers have left Alla Sheehy’s next door. His wife Nora Mai is sweeping the floor. She will be muttering, drawing hard on a cigarette, cursing the hour and the work, under the eternal gaze of the stuffed fox on the counter. A Garda will pass soon on his rounds, his ear alert for the murmur of secret drinkers. There are several dozen pubs in Listowel and he will stop to listen at each one. But the only noise is from the dogs barking in the lane between the houses and the sports field.

‘They can sense it,’ my father says. ‘Stay quiet now. Stay quiet and you will hear them.’ He sits at the end of my bed. I can only make out his shape. There is comfort in the tiny orange glow of his cigarette. ‘Listen close,’ he says again, ‘the riders will come soon.’

I am ten years old. My imagination swells in the darkness. My father lives between the story and the reality. He has spent his life faltering between the two. It is his gift and his tragedy. He can make me believe anything.

‘Now! Now! Sit up,’ he says. ‘Do you hear them? They are riding to hell!’

I hear everything that he wills into being: the hooves pounding the midnight earth, the hard music of armour, sword and spur and men’s voices shouting in the late autumn of 1600. Captain Wilmot’s cavalry – armed with the finest muskets Queen Elizabeth’s treasury can procure – stop before the gates of Listowel Castle and by the banks of the River Feale, which flows out of the mountains in neighbouring County Limerick, meandering around Listowel on its way to the Atlantic coast nearby. The garrison refuse to surrender. Above the swift water heads fly. The blood seeps into the salmon pools. Nine Englishmen are killed, but the Irish cannot hold out. They beg for terms but are refused. They must accept the captain’s discretion, which means death in a more or less dreadful form. Wilmot kills them by hanging, a comparative leniency by the bloody standards of the day, according to my father. After the surrender, the legs of eighteen suffocating men kick to the laughter of Wilmot’s men. My father reaches to his throat to mimic the act of hanging.

The priest who is found with the garrison is spared, however. Not for him the breaking of joints with heavy irons, the agonising death that is the fate of another clergymen found near Dingle. The priest has a bargain to offer. He tells Wilmot that the rebel Lord Kerry’s son, ‘but 5 years old … almost naked and besmirched with dirt’,1 has been smuggled out of the castle by an old woman. Who better than the heir to lure the lord into surrender? The old woman and boy are found in a hollow cave and are sent to Dublin with the priest, but their fate is not recorded.

My father pulls ghosts out of history every night. I know that in reality there are no riders as the field behind my grandmother’s house is unmarked when I check it the next morning. ‘Sure that’s your father for the stories,’ Hannah jokes to me when I return. My grandmother has stories too. She is part of more recent wars. If only she would tell me. She fought the English and was threatened with execution. But her stories will remain untold in her own voice.

Читать дальше