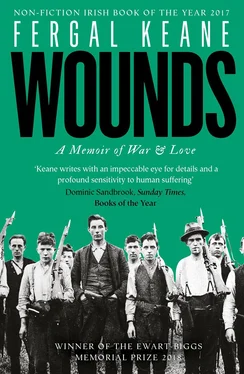

I have tried to avoid yielding to my own collection of biases; however, a story of family such as this cannot be free of the writer’s personal shading. When writing of the Civil War I am acutely conscious that I come from a family that took the pro-Treaty side and, later, became stalwarts of the political organization founded by Michael Collins and his comrades. But I have tried to describe the vicious cycle of violence in north Kerry as it happened at the time and as it was experienced by the people of my past, doing so, as much as possible, without the benefit of hindsight, and without acquiescing to the justifications offered by either side. This book does not set out to be an academic history of the period, or a forensic account of every military encounter or killing in north Kerry. Others have done this with great skill. This is a memoir written about everyday Irish people who found themselves caught up on both sides in the great national drama that followed the rebellion of 1916. It is not a narrative which all historians of the period are sure to agree with, or indeed which other members of my family will necessarily endorse: every one of them will see the past through their own experiences and memories. The one bias to which I will readily admit is a loathing of war and of all who celebrate the killing of their fellow men and women. The good soldier shows humility in the remembrance of horror.

I have reached an age where I find myself constantly looking back in the direction of my forebears, seeking to understand myself, and my preoccupations, through the stories of their lives. It is only with the coming of peace on the island of Ireland that I have felt able to interrogate my family past with the sense of perspective that the dead deserve. It felt too close while blood was being daily spilled in the north. ‘We return to the lives of those who have gone before us,’ wrote the novelist Colum McCann. ‘Until we come home, eventually, to ourselves.’16 Home is where all my journeys of war begin and end.

*On 30 January 1972, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment opened fire on civil rights marchers in Derry, killing thirteen unarmed people. On 2 February angry crowds marched on the British embassy in Dublin and set it alight. In the events that became known as ‘Bloody Friday’ the IRA carried out multiple bombings in central Belfast on 21 July 1972. The attacks claimed the lives of nine people and injured more than one hundred.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.