I am grown and my father is dead when I discover how faithfully he brought the Elizabethan past to life. In the late sixteenth century the conquering English had swept their enemies before them. After capturing Listowel they rode on into Limerick. The president of Munster, Sir George Carew, reported back to London that they had killed ‘all man-kind that were found therein, for a terror to those that should give relief to renegade traitors; thence we came into Arlogh Woods [in County Limerick] where we did the like, not leaving behind us man or beast or corn or cattle’.2 Livestock was slain by the thousand and corn trampled and burned. The Irish peasants were butchered or driven away so that rebels and plotting Spaniards ‘might make no use of them’.3 Ireland was a nest of potential traitors. The possibility of the invasion of England through the ‘back door’, to the west, loomed large in the imaginations of Tudor statesmen and soldiers. Rebellions supported by the pope and the Spanish king reinforced the English terror of the Protestant Reformation being reversed. Such endings, they knew well, only came in tides of blood. Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham had been in Paris on 24 August 1572 and lucky to escape the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Protestant Huguenots. A delighted Pope Gregory XIII offered a Te Deum and had a special medal struck rejoicing that the Catholic people had triumphed ‘over such a perfidious race’.4

The European wars of religion brought an exterminatory savagery to Ireland. In the Munster of my ancestors unknown thousands were killed in battle, slaughtered out of hand, and starved or killed by disease. The severed heads that lined the path to the tent of Sir Humphrey Gilbert – celebrated soldier–explorer and half-brother of Sir Walter Ralegh – were deemed a necessary price for making Ireland a land ripe for the benefits of English civilisation, lining the pockets of English adventurers, and keeping England safe from the existential threat posed by the kings of Catholic Europe.

II

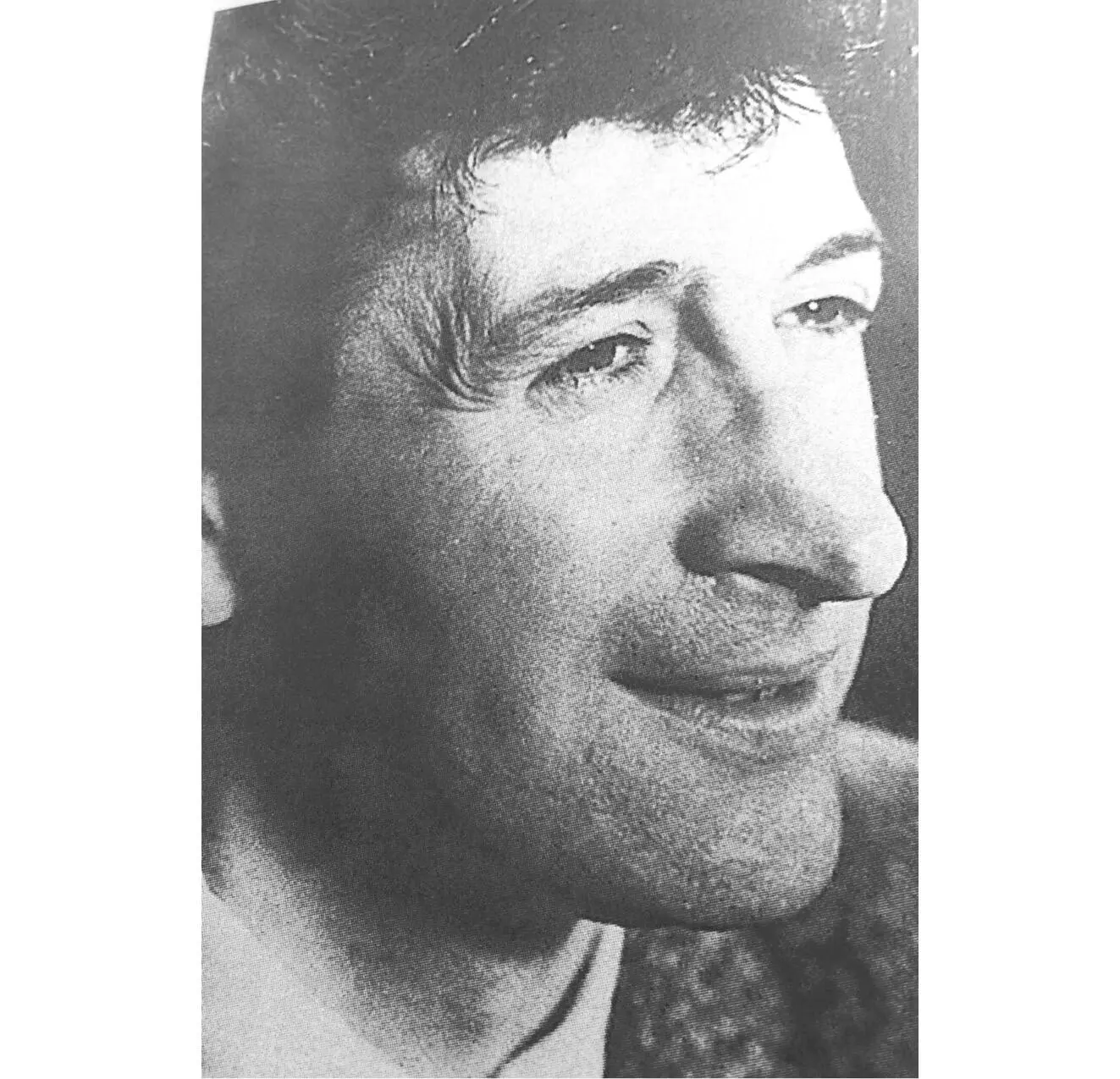

History began with my father’s stories. It was our history. He had no interest in complex agency, only in the evidence of English perfidy of which there was abundant evidence on our long walks during holidays around the ruined castles of north Kerry. Eamonn was a professional actor, one of the most gifted of his generation, and his voice, the rich, beguiling voice of those stories, has followed me all my days. I walked beside him through the lands of the O’Connors – taken by the English Sandes family, who came with Cromwell in 1649 – to Carrigafoyle Castle with its gaping breach where the Spaniards and Italians, and their Irish allies, were massacred fleeing into the mud of the estuary – and to Teampallin Ban on the edge of Listowel where, under the thick summer grass, lay the bones of the Famine dead. That was the ‘hungry grass’ said my father. Walk on the graves and you would always be hungry.

My father the actor ( Author’s Private Collection )

In those days Eamonn was a romantic nationalist. My mother Maura was a supporter of the Irish Labour Party and a committed feminist. She disdained nationalist politics. For her the struggle to achieve equal pay and control over her own body were the greater causes. A memory: being sent to Gleeson’s chemist on the corner in Terenure, five minutes’ walk from home, to ask for a package. The brown paper envelope I carried home contained ‘the pill’, something so secret I could not tell a soul. Only later did I learn how the chemist and my mother, in their quiet way, defied the law of the land which forbade women the right to decide if and when they would have children. Maura was raised in a house where no politics was spoken. Her father, Paddy Hassett, had been an IRA man in Cork but he had left the movement when the Civil War started in 1922. Most of his colleagues took up arms against the new Irish state. The only other trace of the revolutionary past I can find in my mother’s life was her friendship with our neighbour, Philippa McPhillips, niece of Kevin O’Higgins, the Free State Justice Minister assassinated by the IRA in 1927 in revenge for his part in the draconian policy of executing Republican prisoners during the Civil War. It was not a political friendship – they were good neighbours – but my mother always spoke of O’Higgins as a man who had been doing what he believed was his best for the country. He was a man we should remember, she said. Still, when my father suggested I should be named after a dead IRA man, my mother acquiesced: Eamonn Keane was a force of nature and not easily refused. Twenty-year-old Fergal O’Hanlon had been killed during a border campaign raid on an RUC barracks on New Year’s Day 1957. The raid was a disaster, and the IRA campaign faded away for lack of support. But O’Hanlon and his comrade Sean South were ritually immortalised by way of ballad:

Oh hark to the tale of young Fergal Ó hAnluain

Who died in Brookboro’ to make Ireland free

For his heart he had pledged to the cause of his country

And he took to the hills like a bold rapparee

And he feared not to walk to the walls of the barracks

A volley of death poured from window to door

Alas for young Fergal, his life blood for freedom

Oh Brookboro’ pavements profused to pour.

(Maitiú Ó’Cinnéide, 1957)

I grew up in Dublin. The city of the mid- to late 1960s was a place of rapid social change. The crammed tenements of James Joyce’s ‘Nighttown’ with its ‘rows of flimsy houses with gaping doors’,5 were mostly gone, their residents dispatched to the suburban council estates and tower blocks as a new Ireland, impatient for prosperity, straining to be free of dullness and small horizons, came into being. Nationalism had a grip on us still. But it had to compete with other temptations. The city of elderly rebels and glowering bishops was also the home to the poet Seamus Heaney, the budding rock musician Phil Lynott, the young lawyer and future president Mary Robinson; the theatres and actors’ green rooms of my father’s professional life were filled with characters who seemed to live bohemian lives untroubled by the orthodoxies of church and state. The country’s most famous gay couple – though it could never be stated openly – ran the Gate Theatre next to the Garden of Remembrance where the heroes of the 1916 rebellion were commemorated. My mother intimated that Micheál McLiammóir and Hilton Edwards were ‘different’ and left it at that. To me they were simply a slightly more mysterious element in the noisy, extravagant, colourful world through which my father moved in the late 1960s. They were part of my cultural milieu, along with English football teams and imported American television series. Still, my father’s attachment to romantic nationalism defined how I saw history. Or I should say how I ‘felt’ history – because thinking played much the lesser part of all that I absorbed in those days.

Dominic Behan visited our home in Dublin. So did the Sinn Féin leader and IRA man Tomás Mac Giolla, and several other Republican luminaries, though by then the IRA was drifting far to the left. My father played the role of the martyred hero Robert Emmet in a benefit concert for Sinn Féin. By that stage the leadership of the organization had drifted to the left, towards doctrinaire Marxism and away from the militarist nationalism of earlier times, but it could still summon up the martyred dead to rally more traditional supporters. My father never hated the English as a people. In drink he would swear damnation on the ghost of Cromwell and weep over the loss of ‘the north’. But he was too imbued with the magic of the English language to be capable of cultural or racial chauvinism. Shakespeare and Laurence Sterne and John Keats had lived in his head since childhood. In one of his many flights of fancy he would even claim kinship with the great Shakespearean English actor Edmund Kean.

Читать дальше