WALTHAM ABBEY: HOLY CROSS – sturdy Norman arcades sometimes survive in churches that have been much altered in later centuries, though not all are carved with as much grace as these very decorative columns for the abbey church

© Michael Ellis

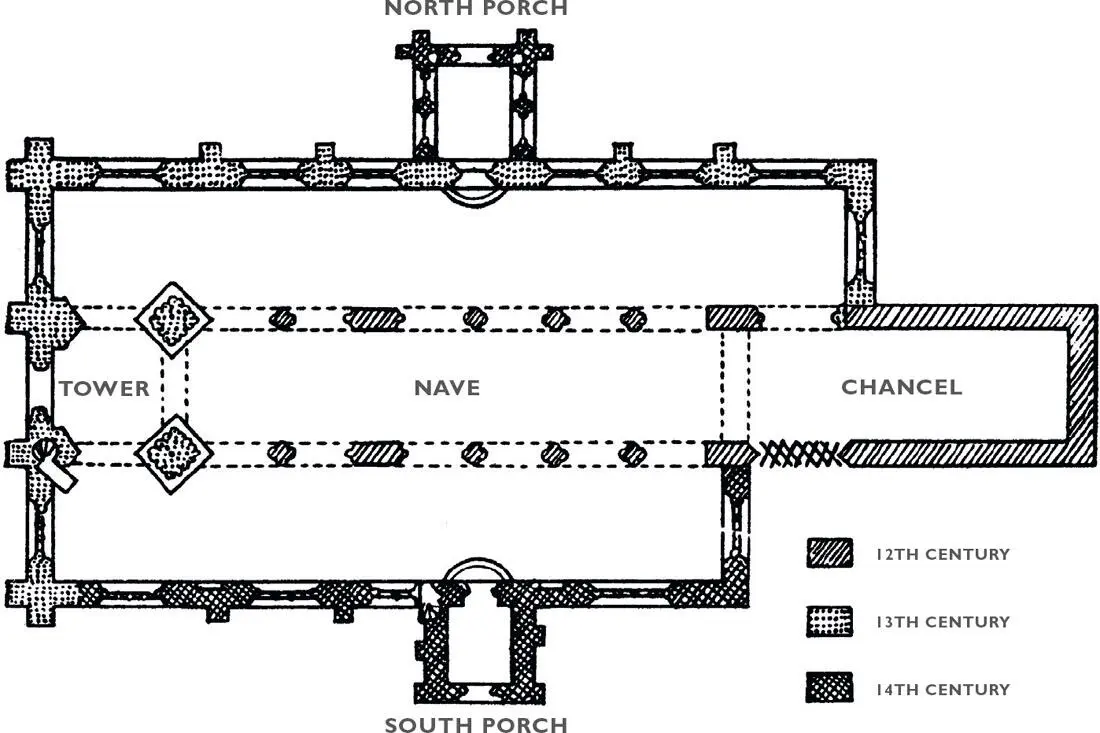

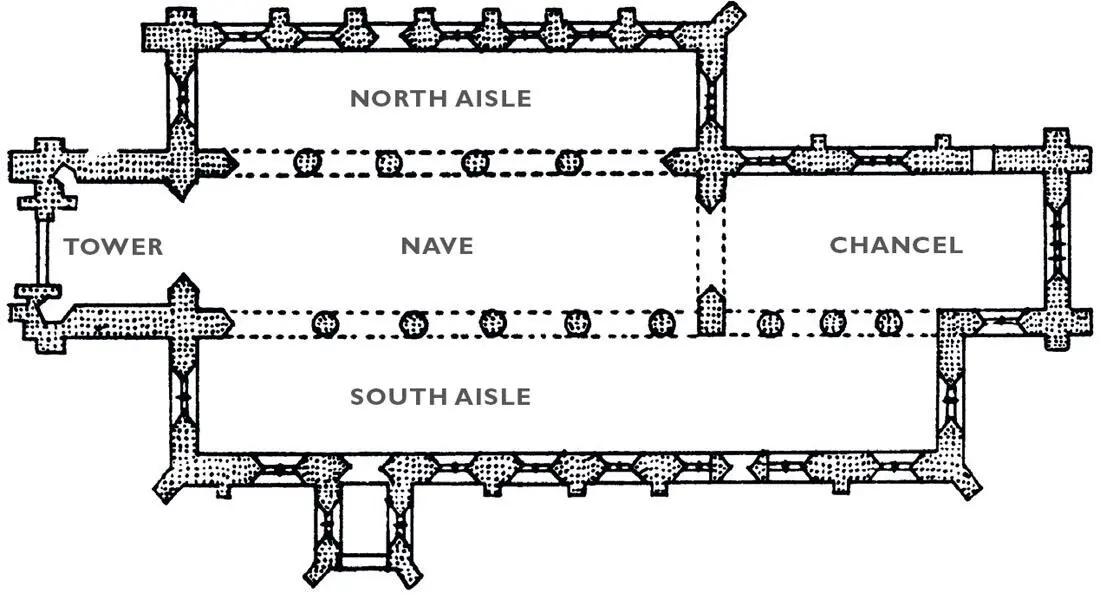

GOTHIC ADDITIONS TO A NORMAN PLAN – Based on Raunds, Northamptonshire: probably this was a Norman aisleless church consisting of nave and chancel of equal width. A tower and north aisle ot the nave were added in the 13th century. In the 14th century a south aisle was added. The original Norman walls were pierced and turned into arcades.

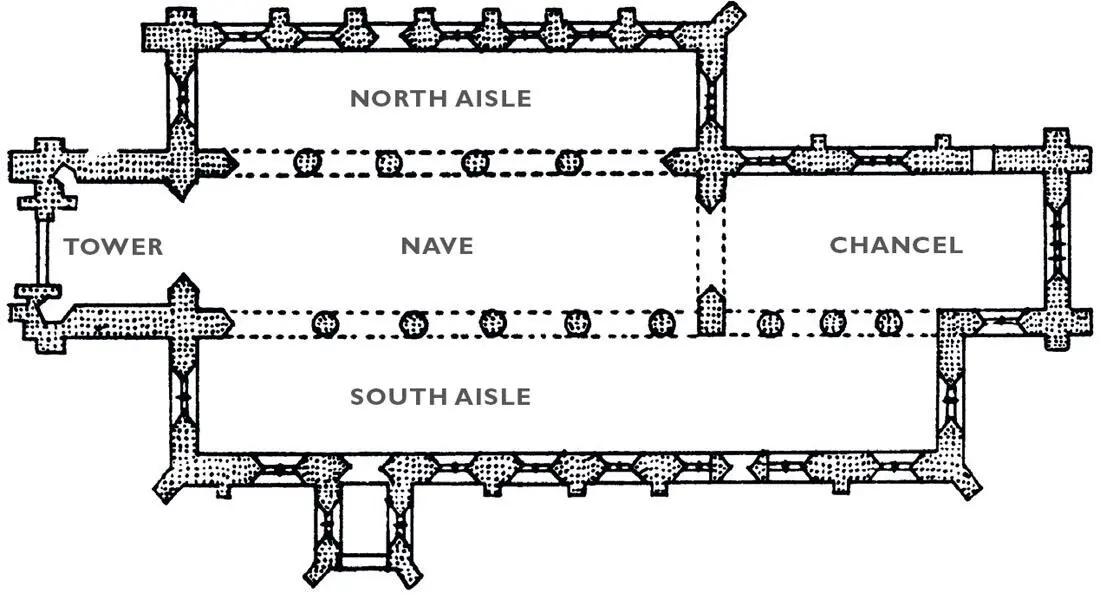

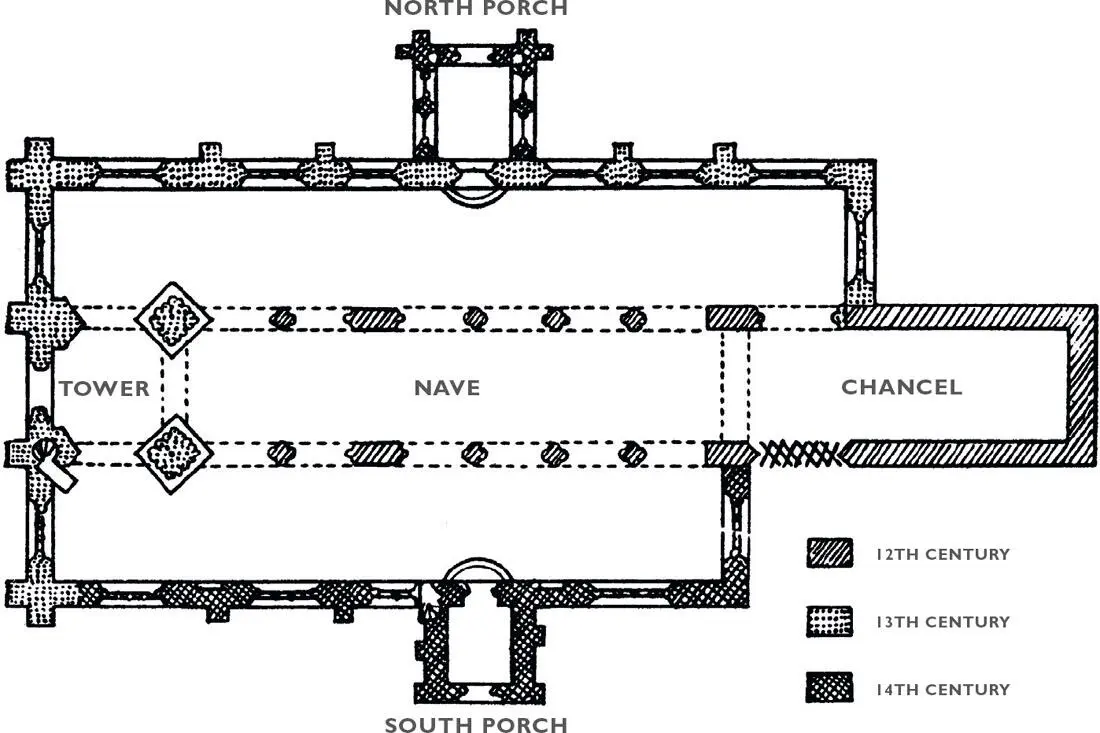

A TOWN CHURCH ENLARGED IN THE 13TH AND 14TH CENTURIES SO AS TO PROVIDE GUILD CHAPELS – Based on Grantham, Lincolnshire

The splays of the windows in the nave have figures of saints painted on them. But it is through the chancel that we see the greatest riches. Stained glass is rare. If there is any it is in the sanctuary and black with much leading and giving the impression of transparent mosaics. The walls are painted everywhere with figures, also recalling mosaic pictures. There are bands of classic style, patterns dividing them. The altar is of stone, small and box-like, recalling the tombs of Christians in the catacombs of Rome in the very earliest days of Christianity. The altar stands well away from the eastern, semi-circular end of the apse. It is covered with a cloth hanging over its four sides, decorated with vertical bands.

Our Lord is depicted on the cross as a King and Judge, not as a man in anguish as in later crucifixions. The religion of the time was less concerned with Him and Our Lady as human beings, more concerned with the facts of Judgement, Death and Hell. It was more ascetic and severe.

PART TWO: THE NEWER CHURCHES

Of the 16,000 parish churches in England more than half have been built since the 17th century, and the majority of these were erected in the 19th and 20th centuries. Guide books, almost wholly antiquarian in outlook, still dismiss even 18th-century churches as ‘modern’, while Victorian buildings are usually beneath their consideration. Yet some of the noblest churches are post-Reformation, from cathedrals like St Paul’s and Truro and Liverpool, to the great town churches designed by such architects as Hawksmoor, Gibbs, Street, Butterfield, Pearson, Brooks, Nicholson and Comper.

The first post-Reformation churches differed little in plan from those of medieval times. Wren in some of his churches for the City of London seems to have tried to build uncompartmented churches, where Baptism, Morning and Evening Prayer and Holy Communion could all be conducted in an undivided space, without the priest and his assistants moving out of sight and earshot.

Usually the plan was the nave with three-decker pulpit dominating for Matins, Litany and Evensong, a screen through which the congregation passed for Communion, and a Bapistry at the west end. The earliest post-Reformation churches usually had west galleries for organ and choir and also side galleries, because by the 17th century the population had begun to increase, especially in the towns where many new churches were built. The churches of the 17th and 18th centuries were mostly built on the English medieval plan. The only noticeable new feature in the more traditional churches was that the chancels were shallower and broader than those surviving from earlier times.

The style of tracery and decoration and wood-carving certainly changed. Windows were square-headed in the 16th century, and thereafter became round-headed. Grapes and cherubs and a cornucopia of fruit cascaded down the sides of altar-pieces, wreathed round the panelling of pulpits, and flattened themselves into patterns on the ceiling. The Renaissance style of Italy became the fashion. But it was an English version. Wren’s Portland stone steeples and lead spires, so happily clustering round St Paul’s Cathedral, are a recollection of Gothic architecture, though most of them are Renaissance in detail.

The interior of even the most room-like classic church of the 17th and early 18th centuries generally differs from its contemporary Dissenting interior. In the former there is provision for the expounding of the Word, and for the two chief sacraments; in the latter there is provision for the Word, but there is no suggestion of an altar about the table that is set for Communion. There may be some significance in the hour-glasses so often found beside the Anglican pulpits. They were intended as a check on the length of the sermon, and perhaps as a reminder to parson and people that there were other offices of the Church to be performed than preaching. Only for the short period when the Commonwealth ejected ordained priests of the Church, who returned with the Restoration, can these interiors have resembled Dissenting meeting houses.

Some of our finest scuplture is to be found in the monuments erected in all parish churches new or old during the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries. A whole illustrated literature of this has been developed by the late Mrs Esdaile and Mr Rupert Gunnis. The work of great sculptors ignored or despised by the Victorians, such as Roubiliac, Rysbrack, Stone, Wilton, the Bacons, Hickey and Paty, has received recognition owing to their writings.

From the middle of the 18th century until its end, new churches were Classic, usually in the manner of the Brothers Adam, with chaste decorations in low relief in interior plaster and woodwork, and comparatively plain exteriors. The individuality of architects was beginning to assert itself over traditional plan and local styles. Cross-shaped churches were built with altar at the eastern axis and there were square and octagonal churches as well as proprietary chapels with the pews all arranged for a view of the occupier of the pulpit. These last buildings came as near to a Dissenting chapel as Anglicanism permitted.

Gothic never died. The style was driven by the Renaissance out of churches and houses into barns, farms and cottages. It was revived in a romantic form, suggesting Strawberry Hill (1733), even in the 17th century. And a slender case might be made for its never having died even in ecclesiastical building. There are Stuart churches which are Tudor Gothic, such as Low Ham in Somerset (1624), and Staunton Harold in Leicestershire (1653), which are like late Perpendicular medieval churches, and not a conscious revival but a continuance of the old style. St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, until its rebuilding by Gibbs in 1721, had been continuously rebuilt in the Gothic style since the time of Henry VIII. There are churches like St John’s, Leeds (1632), and Compton Wynyates (1663), which are a mixture of Classic and Tudor Gothic. Then there are the first conscious imitations of old forms by architects, such as Sir William Wilson’s tower of St Mary’s, Warwick (1694), and Wren’s tower and steeple to St Dunstan-in-the-East (1698), and his towers of St Mary Aldermary (1711) and St Michael’s Cornhill (1721). There is an interesting and well-illustrated chapter on this subject of the earlier revival of Gothic in M. Whiffen’s Stuart and Georgian Churches. The plan of these buildings was almost always traditional with an emphasized chancel. Now and then a Lutheran element crept in. In the Gothic church of Teigh in Rutland (1783), the small font is fixed by a brass bracket to the Communion rails. But the seats face north and south and the pulpit is at the west end.

Читать дальше