WINCHCOMBE: ST PETER – the church has a fascinating array of grotesques and gargoyles that seem to mix anguish, fear and broad comedy

© Michael Ellis

So when we walk down a green lane like an ancient cart track towards the ringing church-bells, we can see the power of God in the blossom and trees, remember legends of the saints about birds and stones, and recall miracles that happened in the parish at this or that spot. And on a feast day we can see the churchyard set out with tables for the church ale when Mass is over, and as we enter the nave we can see it thronged below the painted roof and walls with people in the village, young and old, and the rest of the parish crowding in with us. Human nature may not have been better. Life was as full, no doubt, of wrong and terror as it is today. How different it was is expressed in the words of Froude:

‘For, indeed, a change was coming upon the world, the meaning and direction of which even still is hidden from us, a change from era to era. The paths trodden by the footsteps of ages were broken up; old things were passing away and the faith and the life of ten centuries were dissolving like a dream. Chivalry was dying; the abbey and the castle were soon together to crumble into ruins; and all the forms, desires, beliefs, convictions of the old world were passing away never to return. A new continent had risen up beyond the western sea. The floor of heaven, inlaid with stars, had sunk back into an infinite abyss of immeasurable space; and the firm earth itself, unfixed from its foundations, was seen to be but a small atom in the awful vastness of the universe. In the fabric of habit which they had so laboriously built for themselves, mankind were to remain no longer.

And now it is all gone – like an unsubstantial pageant faded; and between us and the old English there lies a gulf of mystery which the prose of the historian will never adequately bridge. They cannot come to us, and our imagination can but feebly penetrate to them. Only among the sleeping on their tombs, some faint conceptions float before us of what these men were when they were alive; and perhaps in the sound of church bells, that peculiar creation of medieval age, which falls upon the ear like the echo of a vanished world.’

The Churches Before The Fifteenth Century

To imagine our church in earliest times of Christian England is, alas, to enter the controversial world of archaeology. There was a Christian Church in the Roman settlement at Silchester, Berkshire, and its remains have been excavated. It had an apse at the west end instead of the east where one would expect it to be, and the altar which is supposed to have been wooden and square, was also in the west. The east end was square. The church is said to be 4th century. Only the foundations remain. The form of worship was probably more like that of the Orthodox church today than the western rite.

But there are enough later pre-Conquest churches remaining to give us an idea of the architecture of those times. They are called Saxon. There are two types. The southern, of which the earliest churches are found in Kent – three in Canterbury, St Mary Lyminge, Reculver, and, most complete, Bradwell, Essex, all of which are 7th century – were the result of the Italian mission of St Augustine, and were reinforced after the coming of St Theodore in 669. In plan and style they resembled certain early Italian churches. The northern group found in Northumberland and Durham are survivals of the Celtic church, and their architecture is said to have come from Gaul, and is more barbaric looking than that of their southern contemporaries. Their three distinctive features were, according to Sir Arthur Clapham, an unusual length of nave, a small chancel, less wide than the nave, and very high side walls. In the northern group, the most complete is Escombe, Durham (7th and early 8th century?), a stern building, nave and chancel only, with squared rubble walls, small windows high up and square or round headed, and a narrow and tall rounded chancel arch. We have a picture of the interiors of these northern churches from near contemporary accounts. The walls and capitals and arch of the sanctuary were adorned ‘with designs and images and many sculptured figures in relief on the stone and pictures with a pleasing variety of colours and a wonderful charm’. We learn, too, of purple hangings and gold and silver ornaments with precious stones. Elsewhere in England the most considerable remains of pre-Conquest work are those at Monkwearmouth (Durham), Jarrow (Durham), Brixworth (Northants), Deerhurst (Glos), Bradford-on-Avon (Wilts), the tower of Earls Barton (Northants), Barton-on-Humber (Lincs), Sompting (Sussex), the Crypts at Repton (Derby), Wing (Bucks), and Hexham (Northumberland). From the pre-Conquest sculpture, like the crosses at Bewcastle and Ruthwell, and the carvings at Langford (Oxon), Romsey (Hants), Bexhill (Sussex), St Dunstan’s Stepney (London), and the moving relief of the Harrowing of Hell in Bristol Cathedral, and from such enrichment as survives in such objects as St Cuthbert’s stole (Durham), the Alfred Jewel in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, the beautiful drawing in the Winchester Psalter and Lindisfarne Gospels in the British Museum, we know that these Romanesque masons, sculptors and illuminators were very fine artists, as fine as there have ever been in England.

EARLS BARTON: ALL SAINTS – a rare surviving Saxon tower, with characteristic stripwork and crude arched bell openings in the top stage; the parapet above is later

© Michael Ellis

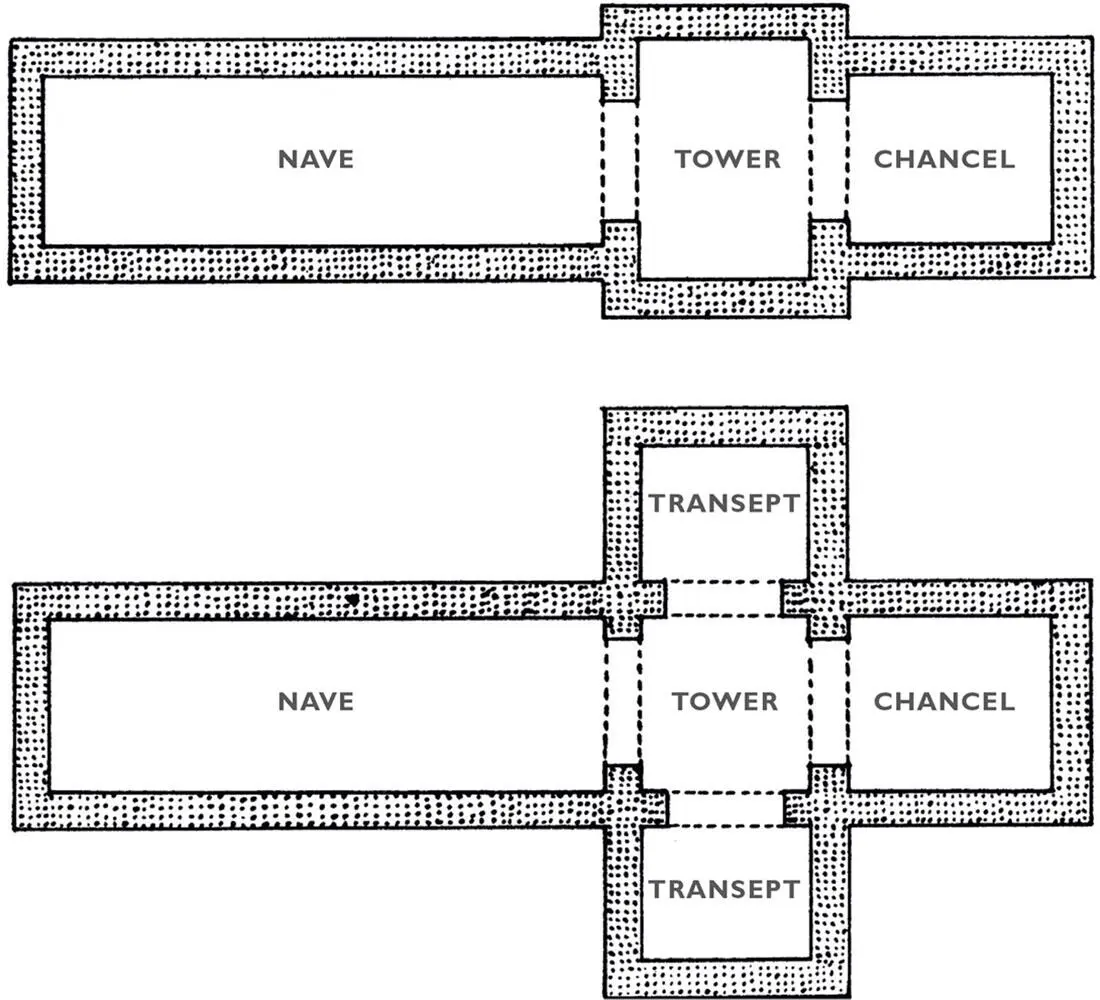

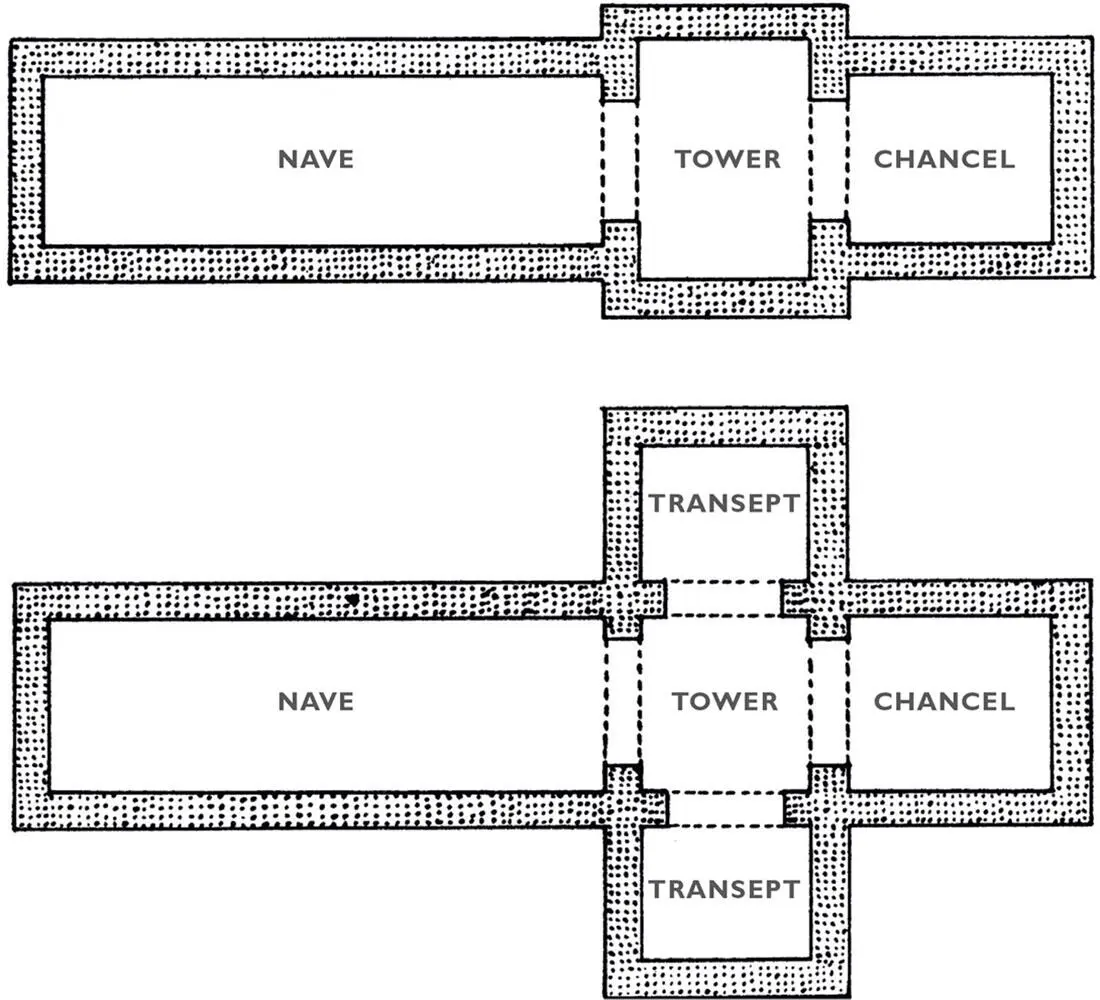

However, it is safer to try to imagine our parish church as it was in Norman times, as far more of our old churches are known to be Norman in origin than pre-Conquest, even though as in the church of Kilpeck (Herefordshire) the pre-Conquest style of decoration may have continued into Norman times. It is narrow and stone built. Let us suppose it divided into three parts. The small, eastward chancel is either square-ended or apsidal. Then comes the tower supported internally on round arches. The nave, west of the low tower, is longer than the chancel. The windows are small and high up. The church is almost like a fortress outside. And it is indeed a fortress of Christianity in a community where pagan memories and practices survive, where barons are like warring kings and monasteries are the centres of faith. These small village churches are like mission churches in a jungle clearing.

ANGLO-SAXON AND NORMAN – Two aisleless plans with central tower. (Top) tower between nave and chancel; (Bottom) tower over crossing of transepts with nave and chancel

There are no porches, and we enter the building by any of the three doors to the nave on the north, south or west. Inside, the walls of the nave are painted with red lines to look like blocks of stone. The raftered roof is hidden by a flat wooden ceiling which is painted with lozenges. The floor of the nave is paved with small blocks of stone or with red tiles. There are no pews. We can only see the chancel through a richly moulded round arch, that very arch which is now the South Door of your parish church. Above this chancel arch is a painted Doom, not quite so terrifying as that of the 15th-century church, for all the painting here is in the manner of the mosaics still seen in basilicas of Italy and eastern Europe.

Читать дальше