1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...22 The Church in the Fifteenth Century

There will be no end to books on the Reformation. It is not my intention to add to them. Rather I would go back to the middle of the 15th century, when the church we have been describing was bright with its new additions of tower, porch, aisles and clerestory windows, and to a medieval England not quite so roseate as that of Cardinal Gasquet, nor yet so crime-ridden as that of Dr Coulton.

The village looks different. The church is by far the most prominent building unless there is a manor-house, and even this is probably a smaller building than the church and more like what we now think of as an old farm. The church is so prominent because the equivalents of cottages in the village are at the grandest ‘cruck houses’ (that is to say tent-like buildings with roofs coming down to the ground), and most are mere hovels. They are grouped round the church and manor-house and look rather like a camp. There is far more forest everywhere, and in all but the Celtic fringes of the island agriculture is strip cultivation, that is to say the tilled land is laid out in long strips with no hedges between and is common to the whole community, as are the grazing rights in various hedged and well-watered fields. There are more sheep than any other animals in these enclosures. The approaches to the village are grassy tracks very muddy in winter. Each village is almost a country to itself. Near the entrance to the churchyard is the church house where the churchwardens store beer or ‘church ales’ for feasts. This is the origin of so many old inns being beside the churchyard in England. The graveyard has no tombstones in it. The dead are buried there but they are remembered not in stone but in the prayers of the priest at the altar at mass. Everyone goes to mass, people from outlying farms stabling their horses outside the churchyard. The church itself looks much the same. The stone tower gleams with new cut ashlar; the walls of the church when they are not ashlar are plastered.

Not only does everyone go to church on Sunday and in his best clothes; the church is used on weekdays too, for it is impossible to say daily prayers in the little hovels in which most of the villagers live. School is taught in the porch, business is carried out by the cross in the market where the booths are (for there are no shops in the village, only open stalls as in market squares today). In the nave of the church on a weekday there are probably people gossiping in some places, while in others there are people praying. There was no privacy in the middle ages, when even princes dined in public and their subjects watched them eat. The nave of the church belonged to the people, and they used it as today we use a village hall or social club. Our new suburban churches which are used as dance halls during the week with sanctuary partitioned off until Sunday, have something in common with the medieval church. But there is this difference: in the middle ages all sport and pleasure, all plays and dancing were ‘under God’. God was near, hanging on his Cross above the chancel arch, and mystically present in the sacrament in the pyx hanging over the altar beyond. His crucifixion was carved on the preaching cross in the churchyard. People were aware of God. They were not priest-ridden in the sense that they bowed meekly to whatever the priest said. They had decided opinions and argued about religion and the clergy, and no doubt some went to church reluctantly. But no one thought of not going to church. They believed men had souls and that their souls must be exercised in worship and customed by sacraments.

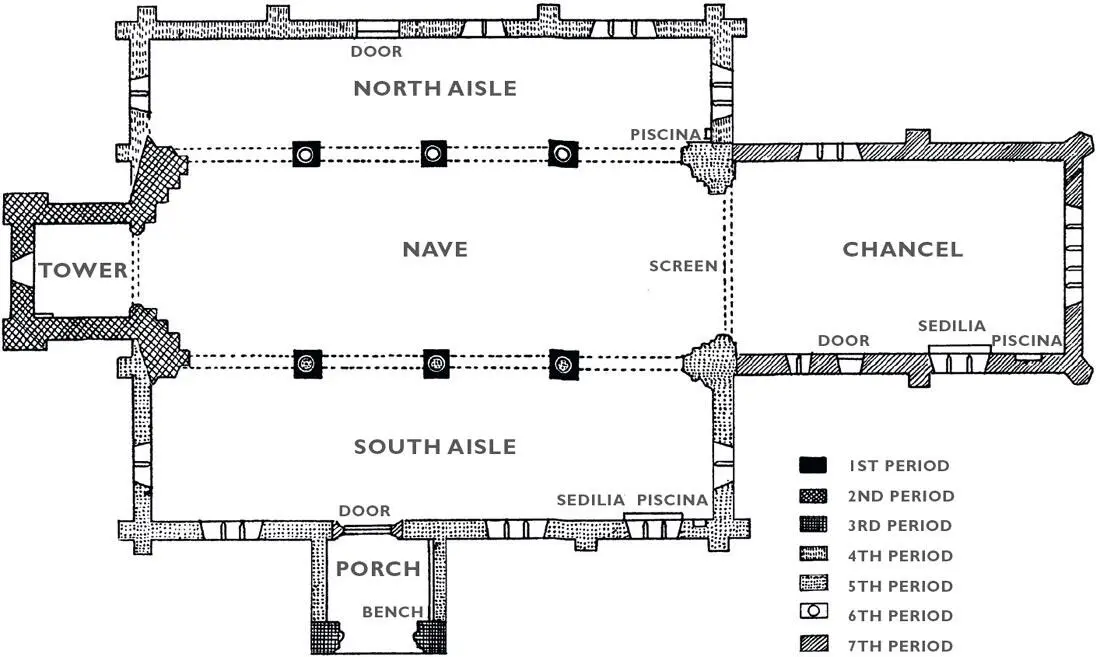

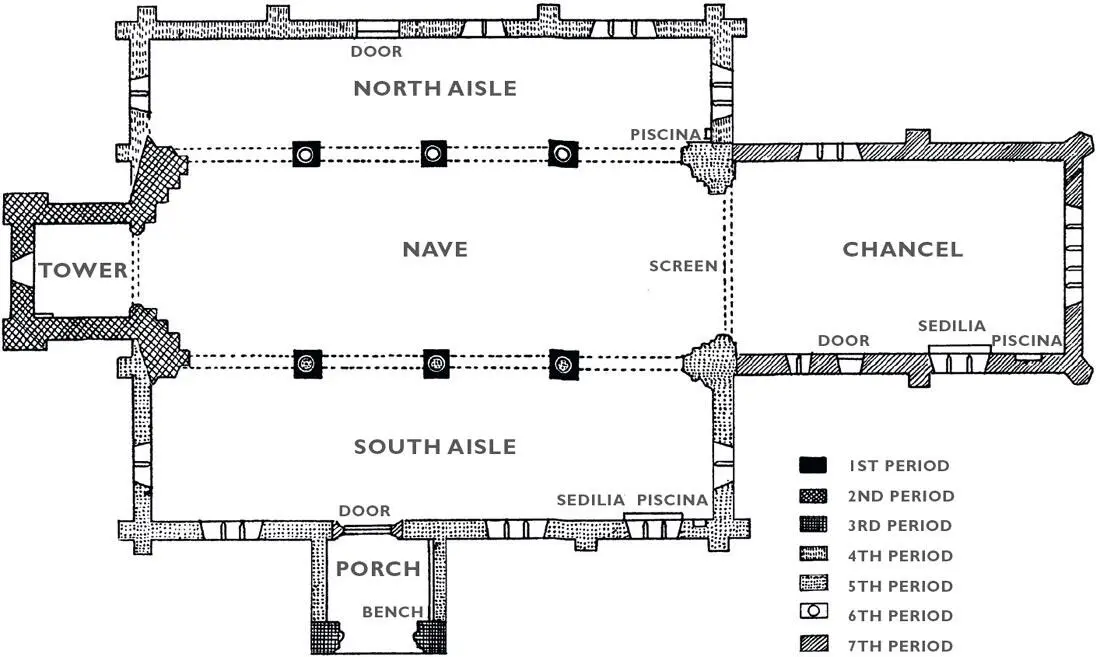

THE GROWTH OF A MEDIEVAL CHURCH – ’At Harringworth in Northamptonshire there had been an aisleless church, to which a tower had been added at the end of the 12th and aisles early in the 13th century. In about 1300 a new north aisle had been built with a new altar at the east end. Soon after the whole of the south aisle and arcade were built. The work was done in a very conservative spirit. During the next few years, the north arcade was entirely rebuilt so as nearly to match that on the south. Thus the work, beginning with the north aisle, and extending over some 30 or 40 years, finished on the side on which it began.’ (From The Ground Plan of the English Parish Church, by A. Hamilton Thompson, 1911)

Let us go in by its new south porch to our parish church of five-hundred years ago. Many of the features which were there when we last saw it are still present, the screen and the font for instance, but the walls are now painted all over. Medieval builders were not concerned with ‘taste’. But they were moved by fashion. If the next village had a new tower, they must have one like it. If the latest style at the nearest big abbey or bishop’s seat made their own building seem out of date, then it must be rebuilt. At the time of which we are writing, the style would be Perpendicular. Only the most shewy features of earlier building – a Norman chancel arch removed in a few instances to the south door, a ‘decorated’ window with rich tracery, and perhaps a column with sculptured foliage capital of Early English times – might be spared if they could be made to look well. The builders were chiefly concerned with making the interior of the church as rich and splendid as possible, something to bring you to your knees. Most parish churches, even the smallest, had three altars, one in the chancel and one on either side of the chancel arch.

WEST HORSLEY: ST MARY – St Christopher carrying an infant Christ on his shoulder was a common theme for medieval wall-paintings; this one could be as early as 13th-century

© Michael Ellis

Where we go in, there is a stoup made of stone or metal, containing Holy Water. And somewhere near, very prominent, is the font. Over it is a painted wooden cover, rising like a church steeple and securely clasped down to the basin of the font and locked. This is because the font contains Baptismal Water, which is changed only twice a year at Easter and Whitsun when it is solemnly blessed. The cover is raised by means of a weight and pulley. The plaster walls are covered with paintings, mostly of a dull brick-red with occasional blues and greens and blacks. The older painting round any surviving Norman windows is picked out in squares to resemble masonry. Chiefly the paintings are pictures. There will be scenes in the life of Our Lady on the north wall, and opposite us probably a huge painting of St Christopher carrying Our Lord as a child on his shoulders and walking through a stream in which fishes are swimming about and fishermen hooking a few out around St Christopher’s feet. It was a pious belief that whoever looked at St Christopher would be safe that day from sudden death. The belief is kept alive today on the dashboards of motor-cars. All the windows will be filled with stained glass, depicting local saints and their legends. Our Lord as a baby and receiving homage as the Saviour will be painted somewhere on the walls. But chiefly there will be pictures and images of Our Lady, who will probably be portrayed more often in the church than her Son. Our Lady was the favourite saint of England, and more old churches are dedicated to her than to anyone else. The Christianity of late medieval England was much concerned with Our Lord as Saviour and Man, and with Our Lady as His mother.

The wooden chancel roofs will all have painted beams, red, green, white and gold and blue. The nave rood may not be painted but over the rood-beam just above the chancel arch it will be more richly carved and painted than elsewhere. The stone floor of the church is often covered with yew boughs or sweet-smelling herbs whose aroma is stronger when crushed underfoot. Strong smells were a feature of medieval life. People did not wash much or change their clothes often, and the stink of middens must have made villages unpleasant places in hot weather. Crushed yew and rosemary must have been a welcome contrast in the cool brightness of the church. Five-hundred years ago, most churches had a few wooden benches in the nave. In some districts, notably Devon, Cornwall and parts of East Anglia, these were elaborately carved. In most places they were plain seats of thick pieces of oak. People often sat along the stone ledges on the wall or on the bases of the pillars. And the pillars of the nave had stone or wooden brackets with statues of saints standing on them. Everywhere in the church there would be images of saints. Though some worshipped these and thought of them as miraculous, such was not the teaching of educated priests of the Church. John Mirk, prior of Lilleshall, who flourished c .1403, wrote thus:

Читать дальше