Vegas Latapié took his leave of Juan Carlos on 6 November as if he would be seeing him the next day. He returned to Switzerland on 7 November. At Lisbon Airport, he gave Pedro Sainz Rodríguez a letter to deliver to the Prince. ‘My beloved Sire, Forgive me for not saying that I was leaving. The kiss that I gave you last night meant goodbye. I have often told you that men don’t cry and, so that you don’t see me cry, I have decided to return to Switzerland before you go to Spain. If anyone dares tell Your Highness that I have abandoned you, you must know that it is not true. They didn’t want me to continue at your side and I have no choice in the matter. When I return to Spain for good, I will visit Your Highness. Your faithful friend who loves you with all his soul asks only that you be good, that God bless you and that occasionally you pray for me. Eugenio Vegas Latapié.’ 109 That such an austere and inflexible character as Vegas could be moved to write such a sad and tender letter testifies to his closeness to the Prince.

It serves to underline that, although there were many political reasons why Juan Carlos had to be educated in Spain, the entire episode could have been handled with greater sensitivity to his emotional needs. Gil Robles wrote in his diary: ‘Vegas may have his defects – who doesn’t? – but nobody outdoes him in loyalty, firmness of purpose, unselfishness and affection for the Prince. And, despite everything, with cold indifference, they just dumped him. How serious a thing is ingratitude, above all in a King!’ 110

It is a telling comment on Don Juan’s attitude to what was about to happen that he did not spend the day before the journey with his son. A perplexed Gil Robles wrote in his diary: ‘he’s gone hunting as if nothing was happening.’ 111 In an effort to ensure that there would be no demonstrations at the main station in Lisbon, the tearful ten-year-old Juan Carlos was waved off by his tight-lipped parents as he joined the Lusitania overnight express on the evening of 8 November at En troncamento, a railway junction far to the north of the capital. If there was one thing that might have diminished a ten-year-old boy’s sadness at having to leave his parents it was the possibility of a spell driving a train. However, that pleasure was monopolized by a grandee, the Duque de Zaragoza, decked out in blue overalls. For his journey into the unknown, the young Prince was accompanied by two sombre adults, the Duque de Sotomayor, as head of the royal household, and Juan Luis Roca de Togores, the Vizconde de Rocamora, as mayordomo .

At first Juan Carlos dozed fitfully but then slept as the train trundled in darkness through the drought-stricken hills of Extremadura. As they entered New Castile in the early light of dawn, he was awakened by the Duque. Burning with curiosity about the mysterious land of which he had heard so much but never visited, he pressed his face to the window. What he saw bore no resemblance to the deep greens of Portugal. Juan Carlos was taken aback by the harsh and arid landscape. Austere olive groves were interrupted by scrubland dotted with rocky outcrops. As they neared Madrid, the boy’s impressions of the impoverished Castilian plain were every bit as depressing. He did not know it yet, but he was saying goodbye to his childhood. What awaited him the next morning could hardly have been more forbidding. The train was halted outside the capital at the small station of Villaverde, lest there be clashes between monarchists and Falangists. As he stepped from the train, shuddering as the biting Castilian cold hit him, his heart must have fallen when he saw the grim welcoming committee. A group of unsmiling adults in black overcoats peered at him from under their trilbies. The Duque de Sotomayor presented them – Julio Danvila, the Conde de Fontanar, José María Oriol, the Conde de Rodezno – and as the boy raised his hand to be shaken, out came the empty formalities, ‘Did Your Highness have a good trip?’ ‘Your Highness is not too tired?’ Their stiffness was obviously in part due to the fact that middle-aged men have little in common with ten-year-old boys. However, it may also have reflected their own mixed feelings regarding the rivalry between Franco and Don Juan. For all that they were apparently partisans of Don Juan, their social and economic privileges were closely linked to the survival of Franco’s authoritarian regime. The Prince came from Portugal deeply aware of his loneliness. Surrounded by such men, he can only have felt even more lonely.

The extent to which he was just a player in a theatrical production mounted for the benefit of others was soon brought home to him. Outside the small station at Villaverde, there awaited a long line of black limousines – the vehicles of members of the aristocracy who had come to greet the Prince and to attend the ceremony that followed. Without any enquiry as to his wishes, the Duque de Sotomayor ushered him into the first car and the line of cars drove a few miles to the Cerro de los Angeles, considered the exact centre of Spain. There, his grandfather, Alfonso XIII, had dedicated Spain to the Sacred Heart in 1919. To commemorate that event, a Carmelite convent had been built on the spot. The sanctimonious Julio Danvila, ensuring that the boy should have no doubts about what Franco had done for Spain, hastened to tell him how the statue of Christ that dominated the hill had been ‘condemned to death’ and ‘executed’ by Republican militiamen in 1936. Still without his breakfast, the shivering child was then taken into the convent for what seemed to him an interminable mass. When mass was over, his ordeal continued. In a symbolic ceremony, he was asked to read out the text of his grandfather’s speech from 1919. Nervous and freezing, he did so in a halting voice. Only then was he driven to Las Jarillas, the country house put at his disposal by Alfonso Urquijo, a friend of his father. 112

It was an awkward moment since, on the same evening that Juan Carlos left Lisbon, Carlos Méndez, a young monarchist, died in prison in Madrid. A large group of monarchists, who had attended the funeral at the Almudena cemetery, came to Las Jarillas to greet the Prince.

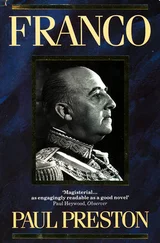

Many monarchists were demoralized by what they saw as Don Juan’s capitulation to Franco. The limits of the Caudillo’s commitment to a Borbón restoration were starkly brought home to Don Juan when Franco refused to permit the young Prince to use the title Príncipe de Asturias. A group of tutors of firm pro-Francoist loyalty was arranged for the young Prince. Juan Carlos expected to be received by Franco on 10 November at El Pardo but because of the situation provoked by the death of Carlos Méndez, the visit was postponed. It finally took place on 24 November. The ten-year-old approached the meeting with considerable trepidation and, as he put it himself, ‘understood little of what was being planned around me, but I knew very well that Franco was the man who caused such worry for my father, who was preventing his return to Spain and who allowed the papers to say such terrible things about him’. Before the boy’s departure, Don Juan had given his son precise instructions: ‘When you meet Franco, listen to what he tells you, but say as little as possible. Be polite and reply briefly to his questions. A mouth tight shut lets in no flies.’

The day of the visit was bitterly cold, and the sierra to the north of Madrid was covered with snow. The meeting was orchestrated with great discretion, with Danvila and Sotomayor driving Juan Carlos to El Pardo in the former’s private car and without a police escort. The Prince found the palace of El Pardo imposing, with its splendidly attired Moorish Guard at all of the gates. He had never seen so many people in uniform. Franco’s staff thronged the passageways of the palace, speaking always in low voices as if in church. After a lengthy walk through many gloomy salons, the Prince was finally greeted by Franco. He was rather taken aback by the rotund Caudillo who was much shorter and more pot-bellied than he had appeared in photographs. The dictator’s smile seemed to him forced. He asked the boy about his father. To Juan Carlos’s surprise, Franco referred to Don Juan as ‘His Highness’ and not ‘His Majesty’. To Franco’s visible annoyance, the boy replied, ‘The King is well, thank you.’ He enquired about Juan Carlos’s studies and invited him to join him in a pheasant hunt. In fact, the young Prince was paying little attention since he was transfixed by the sight of a little mouse that was running around the legs of Franco’s chair. Franco was, according to Danvila, ‘delighted with the Prince’.

Читать дальше