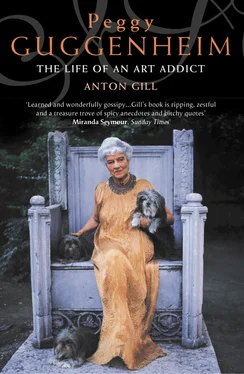

Above all, despite all attempts at assimilation, Peggy was marked by her Jewishness. She belonged to a family within the Jewish New York community which was still regarded as arriviste despite its great wealth, and she was a member of the poorest branch of that family. She experienced anti-Semitism early on, and understood the refugee society’s eternal need to stick together and find security in money – Peggy was only second-generation American. Both her grandfathers had come from the middle-European Jewish peasantry and had started out in America as peddlers. From them she inherited two basic characteristics of the successful trader: a love of money and a disinclination to part with it without good reason. If she didn’t set out to make money, in the end what she invested in pictures repaid itself a thousandfold. In leaving Peggy without the fortune her cousins enjoyed, Ben, ironically, did her a favour.

CHAPTER 3 Guggenheims and Seligmans

Both Peggy’s grandfathers left Europe – Meyer Guggenheim in 1847, James Seligman in 1838 – to escape the financial and professional restrictions placed on Jews in the Old World. The Jewish communities of Europe were centuries old, but since the Crusades Jews had found themselves increasingly the object of mistrust, suspicion and fear. The communities defensively kept to themselves and did not integrate, but the countries in which they lived regarded them as at best unwelcome guests, and promulgated laws which ensured that life for them was as difficult and uncomfortable as possible. The majority of them lived in small rural settlements in eastern Europe and Russia, and were not allowed to farm or own land other than their own homes; even such ownership was subject to tariffs and taxes Christians were exempt from. Jews were not allowed to engage in mining, or the smelting of metal, or any other major industrial enterprise, or to practise in any of the professions outside their faith. The only jobs that remained open to them were tailoring, peddling, small-time retail in commodities, and moneylending. The Church permitted them to deal in moneylending because it considered Jews exempt from two tenets, ironically enough from the Old Testament: Exodus 22, verse 25: ‘If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer, neither shalt thou lay upon him usury’; and Deuteronomy 23, verse 19: ‘Thou shalt not lend upon usury to thy brother; usury of money, usury of victuals, usury of any thing that is lent upon usury.’ Pragmatically, the Church acknowledged the necessity for moneylending, but also saw that it was unpopular, and so, with political acumen, accorded the right to practise it to the Jews.

The origin of the Guggenheim family is uncertain, but it is possible that they originally came from what is now called Jügesheim, to the south-east of Frankfurt-am-Main. By the end of the seventeenth century the Guggenheims had moved to Switzerland from Germany, where the treatment of the Jews was harsher. In Switzerland the Jewish community enjoyed a monopoly on moneylending; but as commerce grew and money increasingly began to be used as capital for ventures, the advantages of lending it on interest began to be seen as sound business practice, and the Church’s prohibition on Christian usury was relaxed at the Fifth Lateran Council of 1512–18. The principal function of Jews in Switzerland thus became superfluous, and, with a growing Christian population, the cantons began to expel them. By the end of the eighteenth century the Jewish population of the entire country was reduced to two small communities, in Ober Endingen and Lengnau.

It was in Lengnau, a small village about twenty-five miles north-west of Zürich, that the Guggenheims settled. The earliest of Peggy’s ancestors on her father’s side whom we can trace for certain was a man called Jakob. Jakob Guggenheim was an elder of the synagogue and a respected local scholar of the Talmud, whose acquaintance was sought by a relatively enlightened Protestant Zürich pastor called Johann Ulrich, who had taken his arthritic wife to the nearby spa town of Baden in about 1740. As a result of their meeting Ulrich, already interested in Judaism, became a friend, but unfortunately the pastor’s proselytising zeal led him to persuade one of Jakob’s sons, Josef, to convert to Christianity. The procedure took sixteen tormented years as the sensitive and intellectual Josef struggled with his conscience. It broke up the friendship; but the Guggenheims had had their first brush with the politically dominant religion. Jakob’s protest at his son’s conversion was so angry that he incurred the wrath of the Christian community, which obliged him to pay a massive six-hundred-florin fine in order to remain in Lengnau. That he could afford it shows how prosperous the family was.

Jews were still allowed to lend money, and another of Jakob’s sons, Isaac, displayed a particular gift for the business. When he died in 1807 at an advanced age, he left 25,000 florins in coin, plate and goods; but life continued to be hard for the Jews of Lengnau, and by the time Isaac’s grandchildren reached maturity his patrimony had all but disappeared.

One of them, Simon, worked as a tailor in the village for thirty years without any significant financial gain to show for it. He lost his wife in 1836, and had to bring up a son, Meyer, and four surviving daughters alone. By 1847 Meyer was nearly twenty and worked as a peddler, travelling in Switzerland and Germany. The younger daughters, though, presented a problem: Simon didn’t have enough of the money required by Swiss law (as applied to Jews) to provide them with dowries (which would then be taxed), so they were not allowed to marry.

The problem of matrimony touched Simon personally. He was fifty-five in 1847, but had become attached to a widow, Rachel Weil Meyer, fourteen years his junior. She had three sons and four daughters, but she also had a reasonable amount of capital. This, together with the value of Simon’s home and contents, should have been enough, they hoped, to persuade the authorities that they themselves had sufficient money to get married. But the authorities were unimpressed. Simon and Rachel had had enough. They began to look for a solution away from home.

In 1819 the Savannah , built at Savannah, Georgia, the first steam-assisted sailing ship designed to cross the Atlantic, had made the passage from her home port to Liverpool in twenty-five days. The ship had a full rig of sails, and only used her steam-driven paddles for the small proportion of the voyage when there was no wind; but her successful crossing suddenly brought the young republic of the United States much closer to Europe, and foreshadowed an era of relatively cheap, quick and reliable crossings of the ocean. Other, more sophisticated ships soon followed. America sought talent, labour and immigrants to bolster its still comparatively small European population, and to people its huge virgin territories. For the Jews of Europe the country had one massive attraction: there were no ghettos, and no discriminatory restrictions – unless, of course, you were a native American.

Jews from rural Germany, especially rural Bavaria, a very hard-pressed region, started emigrating early on, and their letters home carried nothing but praise for the New World. It was a huge step for Simon and Rachel, by the standards of the time already both well advanced in years, and rural Swiss-Germans with no other experience of the world; but repression at home offered them little alternative. Here was a place where they could live freely, not as barely tolerated and exploited ‘guests’, even though their family roots reached back centuries. They sold Simon’s property, pooled their resources, and set off with their children overland for Koblenz.

Читать дальше