William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © James Stourton 2016

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

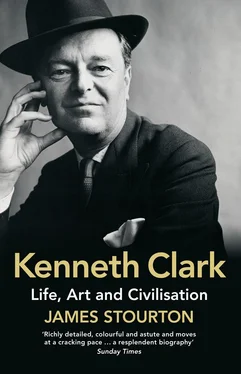

Cover photograph of Sir Kenneth Clark, England, 1958 © The Irving Penn Foundation

Unless otherwise stated, images are from the Clark family archives

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material, the author and publisher would be grateful to be notified of any errors or omissions in the above list that can be rectified in future editions of this book.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007493449

Ebook Edition © September 2016 ISBN: 9780007493432

Version: 2017-08-02

To Colette, Jane and Fram

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

1 ‘K’

AESTHETE’S PROGRESS

2 Edwardian Childhood

3 Winchester

4 Oxford

5 Florence, and Love

6 BB

7 The Gothic Revival

8 The Italian Exhibition

9 The Ashmolean

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

10 Appointment and Trustees

11 By Royal Command

12 The Great Clark Boom

13 Running the Gallery

14 Lecturing and Leonardo

15 Director versus Staff

16 The Listener and the Artists

WORLD WAR II

17 Packing Up: ‘Bury Them in the Bowels of the Earth’

18 The National Gallery at War

19 The Ministry of Information

20 Artists at War

21 The Home Front

22 The Best for the Most

ARTS PANJANDRUM

23 Writing and Lecturing

24 Upper Terrace

25 Town and Country

26 The Naked and the Nude

TELEVISION

27 Inventing Independent Television: ‘A Vital Vulgarity’

28 The Early Television Programmes

SALTWOOD 1953–68

29 Saltwood: The Private Man

30 Public Man: The 1960s

CIVILISATION

31 Civilisation: The Background

32 The Making of Civilisation

33 Civilisation and its Discontents

34 Apotheosis: Lord Clark of Civilisation

LORD CLARK OF CIVILISATION

35 Lord Clark of Suburbia

36 Another Part of the Wood

37 Last Years and Nolwen

Epilogue

Appendix I: The Clark Papers

Appendix II: ‘Suddenly People are Curious About Clark Again’1

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Also by James Stourton

About the Publisher

In his memoirs Kenneth Clark complained that Harold Nicolson ‘could not resist shampooing’ his account of a dinner party, and added the warning that ‘the historian who uses “original documents” must have a built in lie-detector’.1 This is equally true of published material. Clark’s own two volumes of memoirs are exceptionally entertaining, and are both friend and foe to the biographer. Friend, because they cover most of Clark’s life and tell his story more beautifully than any biographer ever could; foe, because Clark wrote them mainly from memory, which was not always reliable – and sometimes verged on the mytho-poetic. Every event needs to be checked against alternative sources; the chronology is loose, and Clark occasionally puts himself at events at which he was demonstrably not present. This was not deliberate on his part, but simply due to the passage of time. The memoirs tell many good stories, although I have reproduced only a tiny handful of them, as they are usually about other people. Since Clark’s own voice is always eloquent I quote him whenever possible; where he has written an alternative and usually earlier account of an event, I have used this for a fresh perspective. An example is the manuscript containing fragments of an art-historical autobiography that he wrote at the end of his life, Aesthete’s Progress , now in his publisher John Murray’s London archive.

Clark did have an eye to history; he kept all his letters to his parents, and rarely threw anything out, even occasionally annotating documents in his own archives. The Clark Archive held at Tate Britain is of a daunting scale, with thousands of letters and documents full of biographical treasures. Clark, however, offered a second warning to a would-be biographer: ‘One realises how little the historian, who must rely on letters and similar documents, can convey a personality. So much depends on the accident of whether or not a character can get himself into his letters.’2 Clark had a famous dislike of both receiving and writing letters, and whenever he could he would dictate them to an assistant. He was too busy to put art into them, but even the briefest will contain a striking phrase; he was incapable of writing a dull sentence. The majority of the letters quoted here are from carbon copies retained by Clark’s various assistants for reference. I have altered Clark’s pervasive use of ampersand to ‘and’, for reasons of flow. Quotations from the Berenson–Clark letters are taken from the excellent Yale edition edited by Robert Cumming.

For the second half of Kenneth Clark’s life we have the astonishing series of letters that he wrote to Janet Stone, which provide a vivid self-portrait, and offer a depth and nuance hitherto unavailable. In these letters his true unbuttoned character is displayed – they were a safety valve, just as a diary was to Pepys or a wartime journal to Lord Alanbrooke. It is tempting to compare these letters to his son Alan’s diaries, but their motivation – beyond the love of writing – was different. The letters to Janet Stone are held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford under a thirty-year moratorium (for reasons explained here). Fortunately, when Dr Fram Dinshaw of St Catherine’s College, Oxford, was appointed to be the original authorised biographer of Kenneth Clark in the 1980s, he was given permission by Janet Stone to read them. All the Stone letters I quote are from Dr Dinshaw’s selected transcriptions.

The biographer of Kenneth Clark is fortunate that both his sons, Alan and Colin, left behind such compelling accounts of their parents. I was equally fortunate in having his daughter Colette, and daughter-in-law Jane, ready to answer questions, and I put it on record that neither of them has at any time attempted to alter anything I have written apart from correcting factual errors. I am lucky to have known some of the main players in the story, John and Myfanwy Piper and Reynolds and Janet Stone, which makes it easier to understand why Clark found them so attractive, and their houses such blessed plots. Virtually all the crew of Civilisation are alive and were able to give me interviews except for Michael Gill, who I met before his death, but alas before I knew I would be so concerned with his story. Perhaps the greatest surprise of all was to find Clark’s favourite television producer from his ATV days in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Michael Redington, not only alive and well but living just three streets away from me in Westminster.

Читать дальше