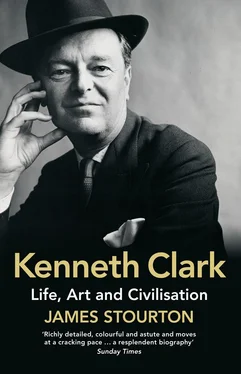

An appetite for public service, born out of the ethos of Winchester, informed Clark’s life; a belief that the elite justified their position through pro bono public works. What was unique about him was his position, through which the creative and academic worlds met those of power and influence. As early as 1959 the Sunday Times thought that ‘It will be difficult to write the definitive history of England in the twentieth century without some reference, somewhere, to Sir Kenneth McKenzie Clark.’8 His role in public life, broadcasting apart, is less obvious to us today; the evidence lies in the minutes of meetings preserved in archives such as Bournemouth (the Independent Broadcasting Authority) and Kew (the Ministry of Information). There are, however, the astonishing outcomes: his hand helped build and guide arts institutions that we all take for granted today: the Arts Council, the Royal Opera House, Independent Television, the National Theatre and countless others. Everybody agreed that his writ ran everywhere: ‘K Clark doesn’t think much of it’ was a knockout blow in debate.9 His success on committees was based on an exceptionally careful reading of the papers, an acute analysis of the options, and a well-thought-out response. He would rarely be the first to speak, and waited to be asked his opinion, which was usually the one that counted. Everybody wanted to know what Clark thought. This was rarely predictable, and in writing this biography I have found that it was impossible to be sure what Clark would think on any subject. Anita Brookner wrote of the ‘unshakeable fairness of outlook [which] may have been his most extraordinary achievement’.10 Clark, however, rarely looked back with satisfaction, and even had a sense of disappointment with his contribution to most of the institutions and boards he joined – except for Covent Garden and the Scottish National Gallery.

What is certain is that Clark never wasted a minute more than he wanted to with people, subjects or institutions. He was extraordinarily disciplined with his time. Everything was timetabled – even friendship and love affairs. He was a master of disengagement. His only relaxation was to write, and what a master of prose he was. If his books are still read today, it is as much as anything because of the pleasure of reading about art described in such beautiful language. Books, lectures, essays and letters poured from his pen in those snatched moments when he was not engaged in public life. The constant question I asked myself while writing this book was, how on earth did he manage to do it all?

Clark always portrayed himself as something of a loner; he honed his lecturing skills as a child, soliloquising on country walks. But he needed an audience; he was a natural teacher who could make any subject interesting. When he was not lecturing to the public, his audience was invariably female – Clark was always most at ease with women. His greatest pleasure in life was to share his interests with a woman. The first of these was his wife Jane. What an extraordinary figure she was: moody, mercurial, expansive, generous, clever, rash, destructive, fascinating, pathetic and magnificent. No single description could ever remotely describe Jane, who Clark needed as ivy needs oak. Her unusual powers of sympathy were exercised on everyone from Margot Fonteyn to the station porters at Sandling, and were matched at home by a shrew-like anger of astonishing force. She is the key to understanding Clark – she was to support him and persecute him, and this cycle was the pattern of their life together. Clark and women are inseparable – they fascinated him, and he made the second half of his life unusually complicated by a series of amitiés amoureuses . But Jane was the greatest love affair of his life, however strange this may appear as the story unfolds.

Clark’s sharpest critics were drawn from his own profession. As the Burlington Magazine pointed out: ‘It has become almost a habit, among a very small minority, to sneer at Clark’s lifestyle.’11 The fact that he lived in a castle made him an irresistible target, and so did his inability to fit into the world of professional art history. With notable exceptions such as Ernst Gombrich and John Pope-Hennessy, his professional peers increasingly viewed him from the 1960s onwards as a non-academic television presenter and literary figure. He did himself no favours by once comparing their scholarly minutiae to knitting. But to the world beyond the Courtauld Institute of Art, whether highbrow or middlebrow, Clark came to represent the popular idea of an art historian. He became an emblem of art and culture to the public. Clark’s own hero in this endeavour was the great nineteenth-century writer and thinker John Ruskin. His debt to Ruskin can never be sufficiently emphasised, and it informed many of his interests: the Gothic Revival, J.M.W. Turner, socialism, and the belief that art criticism can be a branch of literature. But above all, Ruskin taught Clark that art and beauty are everyone’s birthright – and he took that message into the twentieth century. This is the central point of Kenneth Clark’s achievement.

I have been reading … your memoirs. What a strange and lonely childhood – a psychologist’s dream.

DAVID KNOWLES to Kenneth Clark, 27 August 19731

Kenneth Clark’s autobiography has one of the most memorable openings in the language: ‘My parents belonged to a section of society known as “the idle rich”, and although, in that golden age, many people were richer, there can have been few who were idler.’ His account of his belle époque childhood is a minor masterpiece, both subtle and comprehensive. There are virtually no other sources to challenge its veracity, nor is there any reason to doubt its essential truth; despite lapses, Clark had extraordinary recall, not only for events, but also of his feelings and awakenings. Perhaps in this, as in so much of his life, he was following John Ruskin, whose own autobiography Praeterita told the story of the making of an aesthete. Like Ruskin, Clark was an only child, one who was exceptionally sensitive to the visual world and for whom the act of recollection was a reconstruction of his inner life. He was to paint an elegiac picture of his childhood, and even the parts he found distasteful (such as the pheasant shoots) are described with a poetic eye.

When Clark described his childhood he frequently changed his point of view. His children believed that he was unhappy, the victim of dysfunctional parents. His younger son, Colin, summed it up: ‘My father felt very strongly that his parents had neglected him. He thought of his father as a greedy, reckless drunk and always described his mother as selfish and lazy.’2 Yet to others, Clark painted a sunny picture of solitary bliss.3 Both positions can be demonstrated to be true; there were moments of great happiness, and periods of melancholy solitude. It was by any standards a peculiar upbringing. What is perhaps most striking is that young Kenneth had no friends of his own age to play with, and in consequence never learned to relate to other children. Even in infancy he started to build around himself the carapace that Henry Moore later called his ‘glass wall’.

‘I am the type of local boy makes good,’ Clark once wrote to his friend Lord Crawford, ‘like Cecil Beaton as opposed to the Sitwells.’4 As he came from an extremely privileged background, and was educated at Winchester and Oxford, this statement might seem puzzling, but there is a truth behind it. The Clark family were in the mezzanine floor of English society – no longer trade, landed but not gentry. They played no part in traditional county social life, and drew their friends from a raffish band of Scottish industrialists, entertainers and shooting boon companions. Clark was brought up with none of the hereditary culture of the Sitwells. His parents were without any intellectual interests, and he could justifiably see himself as self-created. In practice what his parents failed to provide he sought elsewhere, and few young men have attracted so many mentors or used them to such good effect.

Читать дальше