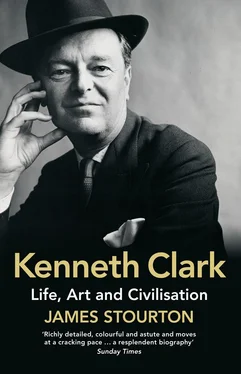

Normally Clark would have left Oxford after graduation at the end of his third year in June 1925, but he decided to stay on for a further year. He informed his mother that he might catalogue Michael Sadler’s collection of modern pictures35 or study one of the great Italian painters, but the project that he actually adopted for his fourth year was suggested by Charles Bell in the week before his final examinations. It was as unexpected as it was original: ‘Write a book on the Gothic Revival.’ Bell had become interested in the topic as librarian of the Oxford Architectural Society. It was an inspired idea. Here was a subject that surrounded Clark at Oxford, and played to his interest in Ruskin. Moreover, ‘these monsters, these unsightly wrecks stranded upon the mud flat of Victorian taste’ required explanation.36 As Clark said, the Gothic Revival was seen as a sort of national misfortune – like the weather – and he was expected to write something satirical in the manner of Lytton Strachey. He described how undergraduates and young dons would break off their afternoon walk to go and have a good laugh at the quadrangle of Keble, which it was universally believed was designed by Ruskin rather than Butterfield.

With so many distractions, Clark was doubtful about the likelihood of his achieving a first in his finals. He wrote to his mother, ‘you must prepare for a steady second’ – which was in fact what he received. He was sanguine about the result, claiming to believe that ‘I have not got a first-class mind’ – but nobody at the time or since has accepted that explanation. Sligger Urquhart reminded him that John Henry Newman and Mark Pattison37 both got seconds, and Clark reminded himself of Ruskin’s honorary fourth. A consoling Bowra wrote: ‘I am so sorry about the schools. I am afraid it will mean your family driving you into the business and that would be terrible. Otherwise it has no importance as experts always get seconds and journalists usually get firsts … nobody else will think the worse of you for not being officially regarded as a master of a subject which bores you to death.’38 It certainly made no difference to Clark’s career, and if it dented his confidence nobody noticed – but it may have curbed his conceit. He undoubtedly had a powerful belief in his own superior gifts, but this was an early indication that these might not lie in a purely academic sphere. The failure to achieve a first may have had a greater influence on his outlook than was apparent at the time, and he eventually became impatient with scholarship for its own sake.

At Oxford Clark had addressed himself most effectively to senior members of the university – he had made a deep impression on older men, all bachelors; but he was now about to exercise his Wunderkind charm on somebody as attached to feminine company as himself.

*‘I see mainly Bobbie and Piers with a good deal of Roger and Maurice and a bit of K. Clark – who is usually bearable for the first three weeks.’ Letter from Cyril Connolly to Noel Blakiston, 25 January 1925 (Connolly, A Romantic Friendship: The Letters of Cyril Connolly to Noel Blakiston ).

*G.N. Clark was interested in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, and there are echoes of his influence in Civilisation episode 8, The Light of Experience .

*Towards the end of his life the poet Thomas Gray (1716–71) fell in love with the young Swiss aristocrat Bonstetten, who lived near his lodgings in Cambridge.

*Perrins was a distinguished books and manuscripts collector. Years later, when Clark was at the Ministry of Information, he wrote to Perrins, who lived near Malvern, stating that if London was bombed the ministry would be evacuated to Malvern, and asking if in that event he could be billeted at Perrins’ house, where ‘I would be less likely than some other evacuees to do violence to your early printed books and pictures.’ Apart from giving away confidential information, the request was highly irregular. Letter to Dyson Perrins, 17 May 1940 (Tate 8812/1/1/6).

*See a letter of protest from Josslyn Hennessy (3 February 1975) about a curious incident when Clark turned on him at a Beefsteak Club lunch after Hennessy had mentioned their first meeting at Oxford: ‘For you said with what, in contrast to your previous manner, struck me as studied politeness, “Now that you remind me of it, I remember it perfectly,” adding after a pause, “That was the time that you were one of the gang who wrecked my room.”’ (Tate 8812/1/4/36.)

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.