Clark’s academic progress was steady but not outstanding by Winchester standards, and he eventually became a house prefect. We can follow the improvements in his reports over a two-year period, 1921–22:

‘Fair report … Mustn’t shirk the dull part of work’

‘Coming on in character’

‘Lack of concentration: must take being a prefect seriously’

‘Plenty of intellectual interests but does not let them prevent his ordinary work’

‘Useful prefect’

‘Must keep art as a hobby and keep a sense of proportion’

‘Brilliant report’

Contrary to the impression given in his autobiography, by 1921, his penultimate year at the school, Clark was regaining the confidence so dented by his first year. He became a conspicuous school intellectual, giving art history lectures and vigorously debating international affairs and post-war politics. We begin to observe the future leader of the arts in Britain finding his feet. He gave a lecture about ‘Wall Decorations’ from Byzantium to Puvis de Chavannes – The Wykehamist reported that his ‘style was free, but somewhat spoilt by the frequency of artist jargon’. The greatest surprise, however, to those who have read his own accounts of his obscurity and shyness at school, is the debates. On 8 November 1921 he opened a debate to speak in favour of benevolent despots, and reflected that there ‘might be found perhaps some educated Dukes … but that there were practically no educated charwomen’. In March 1922 The Wykehamist tells us Clark informed the chamber that ‘To argue was great fun … and concluded on a magnificently journalistic note by enquiring if there was anything more pleasant than to really squash (ugh!) your opponent.’32

Clark had come a long way since the miserable first week at the school. It was now his turn to terrify juniors, though he never did so physically or cruelly. One said, ‘My attitude towards him is, I think, best expressed in the simple word “fear”. He was impatient of stupidity, humbug and conceit … his demeanour was one of urbane ferocity.’33 Clark was in fact undergoing several changes at this time. He was coming to the gradual realisation that his talents lay not in his rather derivative drawings, but in writing and the use of his intellect. He was struck by Matthew Arnold’s dictum that if an Englishman can both write and paint, he should write, for writing is the national form of expression. A few of Clark’s early writings survive, including a story entitled ‘Historical Vignettes: Wonston, 80 A.D.’, ‘written at school for the Library master 1921’. This is a whimsical, rather Shavian dialogue between a wise savage Briton and his foreman, a sophisticated Roman centurion, about the virtues and graces of civilisation.34 What finally cemented Clark’s belief that his future lay with the pen rather than the brush was winning a scholarship to Trinity College, Oxford, in 1922. He liked to pretend that everyone at Winchester was astonished, and nobody more than his housemaster, the Jacker, but the evidence suggests otherwise. The idea suited Clark’s view of himself as an autodidact outside the mainstream.

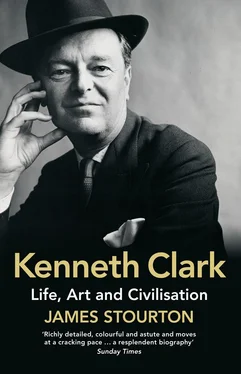

Kenneth Clark was thought later in life to embody certain characteristics that it used to be claimed were Wykehamical: he was astringent of mind, ferociously disciplined, and occasionally chilly. When he was interviewed for a school magazine in 1974, he reflected, ‘It always surprises me when I hear people talk of Wykehamists as a special breed, because you simply cannot group them all together: I was there with David Eccles, Hugh Gaitskell, Cecil King, Dick Crossman, Douglas Jay – possibly the only real Wykehamist among them – John Sparrow and Denis [sic] Lowson; *they were a very mixed lot.’ Winchester produced more than the usual number of socialist intellectuals, but the only one of that list who was to become a close friend of Clark was John Sparrow, who emerged as the tease of the left. Dick Crossman characterised the typical Wykehamist as a ‘blend of intellectual arrogance and conventional good manners’.35 Winchester may not have had the Whig insouciance and Athenian elegance of Eton, but it had a high seriousness of purpose and an intellectual distinction that has produced generations of ambassadors, permanent secretaries, heads of Oxbridge colleges and field marshals. The school encouraged a social conscience, often revealed in public service, and apart from the specific benefits of Rendall, this remained its strongest influence on Clark’s life.

The charm of Golly and his Dutch dolls, who formed such an integral part of his private world, and the affectionate support of Lam may have been rudely interrupted by the male rituals of Winchester, but if the school destroyed the innocent dreams of the solitary boy, it brightened his quicksilver mind and opened it to the possibilities of Italian art, English theatre and poetry, which were to be the sustenance of his life. Every Winchester boy has a note on his file – called ‘Leaves’ – that gives an indication of what happened after he left the school. Clark’s is wonderfully schoolmasterish: ‘Did not get a first in history at Oxford, probably too much drawn off to art: turned to art criticism.’

*‘I read Walter Pater at Winchester but for some reason left this out of the autobiography, a disgraceful omission.’ (BBC, ‘Interview with Basil Taylor’, 8 October 1974, British Library National Sound Archive, Disc 196.)

*Information supplied by the Orford Museum. Today Sudbourne Hall is gone, but the drive, converted stables, model farm and village remain. The trappings of Edwardian wealth are still evident, and the vast empty walled gardens, the cricket pitch and surviving outbuildings speak of the former scale of the establishment.

*In the 1960s Clark would become one of its leading defenders against developers.

*In 1951 Clark funded the reinstallation in Thurbern’s Chantry chapel of four beautiful stained-glass windows from 1393 showing the tree of Jesse, in memory of Rendall. The cost was in excess of £5,000, an enormous sum at the time. See letter to L.H. Lamb, 27 July 1973 (Winchester P6/135).

*The Winchester term for the wooden partitioned area allowed to each boy.

*Sparrow (1906–92), the future Warden of All Souls, was to be a lifelong friend.

*Lord Eccles, Tory politician and Arts Minister; Hugh Gaitskell, Labour leader and Chancellor; Cecil King, newspaper publisher; Richard Crossman, Labour politician and diarist; Douglas Jay, Labour politician; Sir Denys Lowson, much-censured City tycoon.

The most valuable thing about college life is the infection of ideas which takes place during those years. It is like a rapid series of inoculations. People who have not been to college catch ideas late in life and are made ill by them.

KENNETH CLARK to Wesley Hartley, 19 February 19591

In October 1922 Kenneth Clark entered Trinity College with an honorary scholarship, ready to enjoy what he later called the hors d’oeuvres of life. The attractions of Oxford in the 1920s have often been described; the city still breathed from its towers the last enchantments of the Middle Ages, and the suburbs barely encroached on its borders. Clark was part of the famous generation of Oxford undergraduates who came up confident in the jingle

Après la guerre,

There’ll be a good time everywhere.

And yet in that brilliant and colourful gallery which included Harold Acton, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene and Anthony Powell, Clark hardly registers at all. By his own account the reason was his shyness, but he was never likely to be part of the aesthetes’ set which congregated around Christ Church, with its homosexual clubs and flamboyant behaviour. Clark’s own college, Trinity, was small, not especially distinguished, and had a hearty and sporting reputation. A recent president,2 eyeing the alumni portraits in the President’s Lodge, observed that on one wall were all those who had won the colonies, and on the opposite wall were all those who had lost them. If history chiefly remembers Oxford in the twenties for the antics of a few conspicuous undergraduates, it has forgotten that most were ordinary beer-drinking, pipe-smoking sportsmen, and it was these who would generally have confronted Clark in his own college. Clark was faced with the same problem he had had at Winchester of fitting in, and his ‘first feelings at Oxford were of loneliness and a lack of direction’.3 He never joined the Oxford Union or any of the conventional clubs where alliances were forged. Nevertheless, he was to make most of the friendships that carried him through life at the university.

Читать дальше