From there they continued to Hamburg, where they spent only a short time before taking steerage berths on a sailing ship – the cheapest passage they could find – bound for America. The voyage took eight weeks, the conditions were cramped and the travellers had to share them with a flourishing population of rats. Although dried fruit was supplied, the food was basic – chiefly hard-tack – and water was rationed very strictly. There was no privacy.

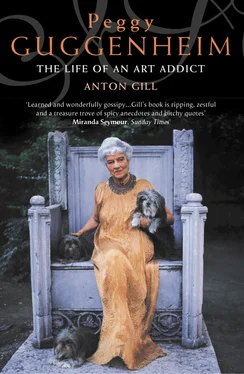

For Simon’s son Meyer and Rachel’s fifteen-year-old daughter Barbara, however, the discomfort of the journey was eclipsed by something far more important: they fell in love. By the time the American coastline rose on the horizon, they had decided – as soon as they could afford it – to marry. This strengthened Meyer’s resolve to do well. He was a small, energetic man, with strong features and a bulbous nose which many of his descendants, including his granddaughter Peggy, would inherit. Capable of kindness, and not averse to the finer things in life (good cigars and fine white wine featured in his later prosperity), he had a liberal side and a certain sense of humour. As a businessman, however, he was habitually mistrustful, cold and acute. He was obsessed with making money, and though he had an aptitude for it, he also worked at it relentlessly.

The joint families’ destination was Philadelphia, where they may already have had friends or relatives – it was the usual method for second- or third-wave immigrants to follow to where cousins or neighbours from the old country had already established bridgeheads, one reason being that few immigrants spoke the language of the new country when they arrived. Away from the north-east, the United States in 1848 was still more or less unexplored: the rapid colonisation and urbanisation of the next seventy years or so was only just getting under way. Philadelphia, however, founded by William Penn in 1682, was by now a prosperous and important city of some 100,000 people, including 2500 Jews. The Jews were integrated into the local community, but only held positions of minor social and financial standing.

Once they had disembarked, organised their modest baggage and adjusted to the unfamiliar, exciting and frightening environment, the large family set about finding a place to live. They rented a house in a poor district outside the city centre, and immediately Simon and Rachel married. The next thing to do, before their slender savings were exhausted, was to find work. Rather than seek employment, Simon and Meyer decided to work for themselves. As it would take more capital than they could afford to set up a tailor’s shop for Simon, they both took to peddling, the work Meyer already had experience in. Stores were few and far between and transport was hard, so most people, especially in outlying areas, tended to buy whatever they needed from travelling salesmen. Old Simon worked the streets of the town, while young Meyer left home each Sunday with a full pack for the country districts, not returning until the following Friday. It can’t have been easy, walking miles on foot, sleeping in the cheapest lodgings, with robbery and abuse a constant worry, but before long he had established both routes and a routine.

The Guggenheims had to learn fast – both the language and local business practice – but on the other hand they were free of all the laws and taxes imposed on Jews back in Switzerland, so there was a sense of liberation which made the graft easier to bear, and also motivated them. For Meyer especially this new beginning was stimulating, and he quickly discovered within himself a great aptitude for business. Iron stoves were rapidly replacing the old open hearths, and one of his best-selling lines was a form of blacklead for cleaning them. Meyer saw that if he could find a way of making his own polish, rather than buying it from the manufacturer, he could make a far greater profit while keeping his retail price low. In those days there was no law restricting such a practice, and history doesn’t relate how the manufacturer reacted to the loss of one small client, but Meyer took a can of the stuff he was buying to a friendly German chemist, who analysed it for him. Thus armed with the recipe, and after several messy experiments in his scant time off, Meyer not only produced his own stove blacking, but improved upon the original by making a version that would stay on the stove, but not on the hands of the person cleaning it. Before long he was selling his polish in such quantities that Simon gave up his own round and stayed home to produce it, using a second-hand sausage-stuffing machine. Soon Meyer was making eight to ten times the profit he had formerly made.

He didn’t stop there. Coffee was already taking hold as the favourite drink of America, but real coffee was extremely expensive. Poorer people drank coffee essence, a liquid concentrate of cheap beans and chicory. Meyer’s step-brother Lehman had already started to produce some of this at home, and now Meyer added it to his list of wares. By this time he was an experienced salesman with a reliable body of customers who trusted him. Four years after getting off the boat he was, at twenty-four, an established figure in the stoveblack and coffee-essence businesses. He married Barbara at Philadelphia’s Keneseth Israël Synagogue and the newlyweds set up house for themselves. It was a good match and a successful marriage. Barbara’s gentle and selfless personality made her the perfect complement to Meyer. She never questioned his authority and always supported him. She was a good mother to their children, and if she had a fault at all it might have been to over-indulge her younger offspring. Meyer, on the other hand, could be a stern disciplinarian. His youngest son, William, recalls in his memoirs that his father had ‘no tendency to spare the rod. Whippings were not infrequent; he employed a leather belt, a hairbrush, or any convenient paddle whenever the need suggested itself to him … None was allowed to doubt for long that his father’s word was law or to think that that law might be broken with impunity.’

From the start, Barbara showed an inclination to charitable work, which increased as her means did, though throughout her life she showed no inclination to use the money her husband earned to spoil or pamper herself. Just as Meyer established the business empire, ruthlessly developed by the more able of his sons after his death, so perhaps did their mother’s influence incline them to set up the charitable foundations for which the family remains famous, after they had made their fortune.

In the course of the next twenty years, Meyer and Barbara produced eight sons, including twin brothers, and three daughters. One of the twins, Robert, died in childhood, and their daughter Jeannette only lived to be twenty-six. But the survivors would grow up to be the heirs and developers of a business empire which was among the biggest half-dozen in America a century ago, and which was gathering strength when Meyer’s granddaughter Peggy was born.

Meanwhile, Meyer expanded and diversified his business interests, always driven by the desire to increase the security of his position in society by making ever larger sums of money. He didn’t necessarily cling to it – the years following his marriage would be punctuated by a series of house moves which tracked his rise in Philadelphia society – but he was extremely careful with it, and would never spend it unless there were some material, political, business or social gain to be made. One of his favourite proverbs came straight from the rural peasantry of his birth: ‘Roast pigeons don’t fly into your mouth by themselves.’ This dictum was one which he tried to inculcate into each of his sons: with Isaac, the oldest, born in 1854, he was not altogether successful, but with the three middle sons, Daniel (1856), Murry (1858) and Solomon (1861), he had greater success. The surviving twin, Simon (1867), also remained within the family fold; the surviving daughters, Rose and Cora, born in 1871 and 1873, following nineteenth-century practice both made good marriages and remained a credit to their parents. Benjamin (1865) and William (1868), however, followed their own paths, as we have seen.

Читать дальше