Several hundred guests were gathering that Tuesday evening twenty years after her death in a more manicured space: neatly flagged and gravelled, with the sculptures openly displayed. Not all of the sculptures now belong to the art collection which Peggy Guggenheim brought here in the late 1940s. Many are part of the collection of the Texan collectors Patsy and Raymond Nasher.

The crowd has assembled in the electrically lit, mosquito-free night. The garden is full. Dress ranges from super-elegant to T-shirt and jeans, but everyone is stylish. Le tout Venise is here to mark the opening of an exhibition commemorating the centenary of Peggy’s birth. Organised by one of her granddaughters, the exhibition has come here from New York, where it opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Solomon was Peggy’s uncle, though their two art collections were separate entities during most of her lifetime. The granddaughter, Karole Vail, is the only Guggenheim grandchild to work for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She is among the guests, in a Fortuny dress, elegantly echoing the Fortuny dress Peggy often wore. Her sister Julia and her cousins are there too – six of the seven surviving grandchildren. Mark has not come. Fabrice died in 1990.

Philip Rylands is the curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. He has been in charge since the palazzo became a public gallery in 1980. Philip is English, and originally came to Venice from Cambridge University to research a doctoral thesis on Jacopo Palma (il Vecchio). He makes a speech in impeccable Italian. During it, as the light through the trees throws changing shadows on the people below, Mia, Julia’s daughter, the only one of Peggy’s great-grandchildren present, twenty-one months old, clambers onto Untitled (1969) by Robert Morris – a huge rectangle of steel balanced on a massive section of steel dowelling, stretched horizontally on the ground. Mia runs up and down. Her activity turns a few heads.

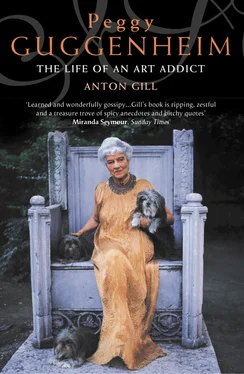

After two hours, people have begun to filter away, and in another hour the garden will be empty. In a corner a stone slab set into a wall marks the resting places of Peggy’s ‘beloved babies’ – fourteen little dogs, until almost the end all pure-bred Lhasa Apsos, which in a series of generations shared Peggy’s life in the palace. Next to it is another plaque. On it is written: ‘Here rests Peggy Guggenheim 1898–1979’.

The party in 1998 filled the garden. Eighteen years earlier, on 4 April 1980, only four people were present for the interment of Peggy’s ashes. She had died an isolated death just before Christmas the previous year.

Although Peggy’s claim to fame is as one of the foremost collectors of modern art of the first half of the twentieth century, her ‘offstage’ life as a restless combination of wanderer and libertine has attracted so much gossip, obloquy, scandal and delight that it has overshadowed her influence as a patron of painters and sculptors. When she was at the peak of her career, feminism was in its infancy and, apart from the Suffragette movement, not organised on any major scale. Men took it for granted that they had precedence over women, and it would be hard to find a more sexist bunch than the male artists who flourished between 1900 and 1960. Peggy took on their world with a mixture of low self-esteem and aggression, aided by money. She couldn’t enter that world as an artist – a difficult task for any woman at the time – but she could use her money to buy a position in it. In her endeavours she never quite found herself, but she supported three of the most important art movements of the last hundred years: Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract-Expressionism.

It took Peggy some time to come to modern art. She was twenty before she held a contemporary painting in her hands, at the photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s boundary-breaking 291 Gallery in New York City – a picture by Stieglitz’s wife-to-be, Georgia O’Keeffe. If she was flirting with Bohemia as early as that – the introduction to Stieglitz stemmed from work in a cousin’s avant-garde bookshop – it would be another twenty years, one husband and many lovers later before she started work on her own account.

At twenty-one, Peggy came into the first slice of what was a relatively slender fortune. In the years following the First World War, Europe beckoned young Americans, and Peggy, used to childhood holidays on the Continent, and for other reasons too, was among the first to go. There she plunged into the world to which she was to belong for the rest of her life, and in which she was to be a star.

The Second World War forced her, as a Jew, to retreat to America. There, in New York, she created a gallery the like of which had not been seen anywhere before, and through it and the salons – if such a word can be applied to the whiskey-and-potato-chips parties she held – in her house overlooking the East River on East 51st Street, she created a forum where young American artists could meet and confront the old guard of European modern art in exile.

The war over, and another marriage unhappily over too, she returned to Europe, and made her home in Venice. It was there that she set about the task of consolidating her collection. She’d been a flapper, she’d been a profligate, she’d been a Maecenas, she’d been a wife, she hadn’t been much of a mother. Now it was time to become a grande dame. Inside, there had always been an inquisitive and lively girl who had never been able to find love.

When I first visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection I was struck by the refreshing contrast to the splendours of Renaissance and Baroque art in which Venice is so rich. It was a palate-cleanser after which one could return happily to the glories of the Scuola San Rocco or the Frari. Peggy herself, hesitating to name any picture in her own collection as her favourite, did have a favourite painting: The Storm by Giorgione (c.1505), in the Accademia, a stone’s throw from her palazzo. She once said she would swap all of her collection for it.

The festa to mark her one hundredth birthday would have amused Peggy by its contrast to her lonely departure from this world, and it would have touched her that so many people were there. She would also have been appalled at the expense.

Later that evening it began to rain again.

‘I was born in New York City on West Sixty-Ninth Street. I don’t remember anything about this. My mother told me that while the nurse was filling her hot water bottle, I rushed into the world with my usual speed and screamed like a cat.’

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM, Out of This Century (1979)

Things had been going badly for Benjamin Guggenheim for a long time. The fact that his marriage was falling apart was something he’d got used to a while back, and, as he admitted to himself, there had been ample consolation – though through it all a nagging lack of satisfaction – for the rapid cooling of his relationship with his wife. The business was another matter. He’d left the family firm eleven years earlier, in 1901, full of injured dignity at what he saw as the high-handed attitude of most of his brothers, determined to go it alone and show them: after all, the expertise he’d picked up in mining and engineering should have stood him in good stead. And, to be fair, it had. Wasn’t his International Steam Pump Company responsible for the lifts that now ran all the way to the top of the Eiffel Tower? And Paris hadn’t been a bad alternative, this past decade, to a loveless, even inimical, New York. If it weren’t for his daughters, Benita, Peggy and Hazel, the three unlikely products of his and Florette’s rare moments of passion (informed by duty) over the first eight years of their union, he might well have cut loose altogether.

Читать дальше